Midnight Express: The cult film that had disastrous consequences for the Turkish tourism industry

Premiering in Cannes this week, Midnight Return, a new film by Sally Sussman, explores one of the most controversial movies of its era

It was one of Alan Parker’s greatest movies – a gut-wrenching prison epic with an Oliver Stone script and pounding Giorgio Moroder music. Midnight Express (1978), produced by David Puttnam, won two Oscars and very quickly assumed cult status. What the filmmakers hadn’t anticipated was just how deeply they had offended the Turkish people or the disastrous consequences their film had on the country‘s tourism industry.

Now, Sally Sussman’s new film Midnight Return, which premieres in Cannes today, explores the legacy of one of the most controversial movies of its era.

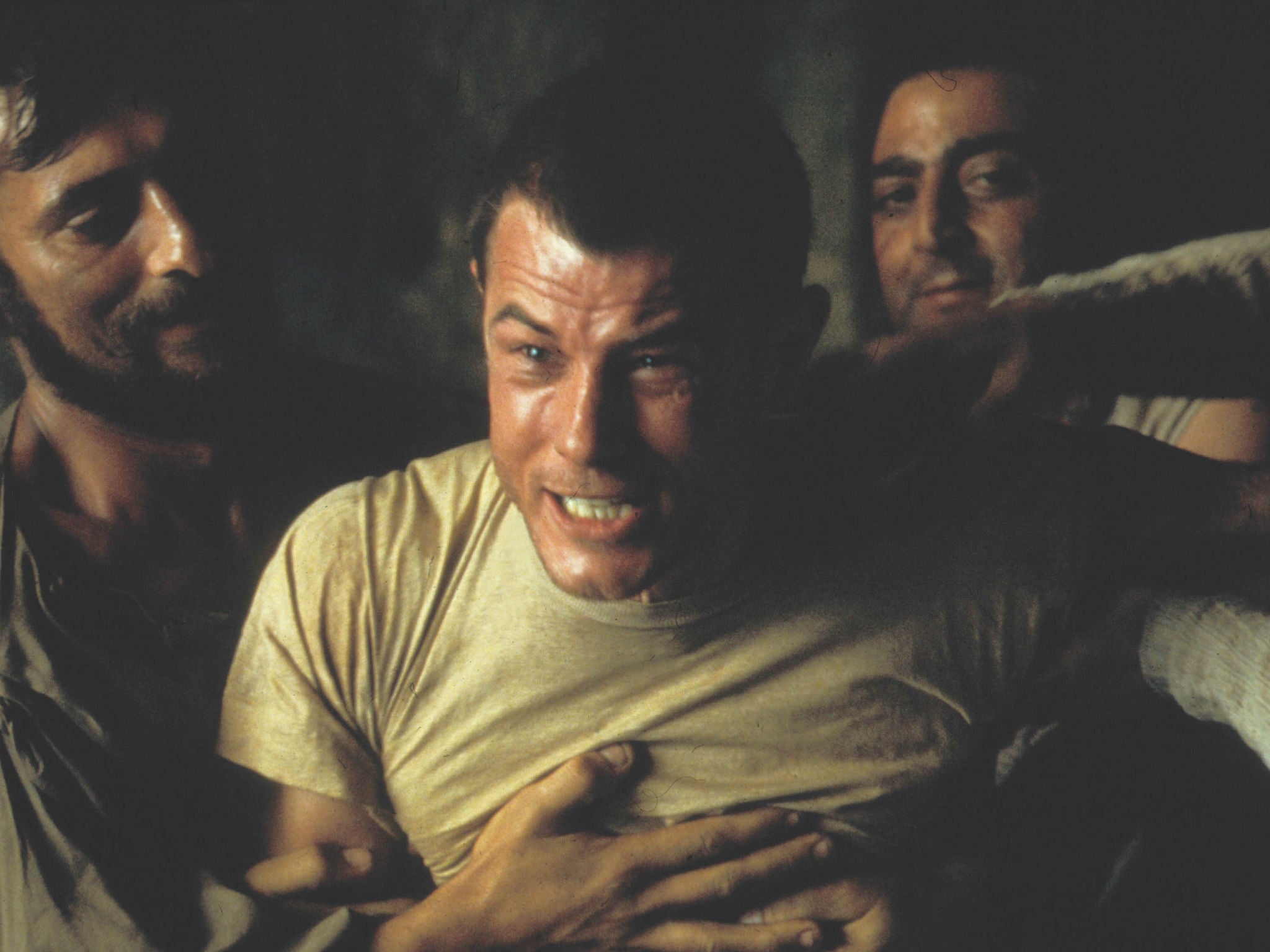

In Midnight Express, a young American, Billy Hayes (played by the late Brad Davis), is arrested at Istanbul airport with some hash taped to his chest. He is thrown in prison and endures a traumatic time at the hands of sadistic prison guards before managing to escape. The film features some brutal scenes, most notoriously the sequence in which Billy, in huge slow motion close-up, is shown biting out the tongue of the Turkish guard. Parker later acknowledged that he got a little bit carried away with this scene which required the unfortunate Davis to spit out a pig’s tongue again and again.

“I’d never seen a movie, ever, that stuck with me the way that movie did,” Californian-based Sussman recalls of when she first saw Parker’s film as a student at the University of Southern California in the late 1970s. “I just remember leaving that film shaking.”

Sussman went to carve out a career as a writer and producer of soap operas such as The Young And The Restless. By coincidence, her husband Tony Morino, knew Hayes, who became a family friend. “The character of Billy Hayes in the film was passive, much more of victim. The real Billy, in prison for the five years, was a very wily character, always plotting, always planning, always hoping he could escape, which he eventually did.”

There was a reason for the casting of Davis. The studio had originally wanted Richard Gere for the role but the filmmakers realised Gere was too much the hero. For the movie really to work, audiences, had to believe that Billy wasn’t going to make it. That’s why they went for a sensitive actor like Davis.

In the documentary, Parker, producer Puttnam and many others involved in the original production appear on screen as does the real Hayes and two fellow prisoners held with him during his nightmare time in a Turkish jail. Sussman explores the impact of Midnight Express on Turkey and on the life of Hayes. “It [Midnight Express] became a huge part of pop culture and it also had political ramifications,” the director says. “It was probably the most hated film ever in Turkey.”

The prison warders are portrayed as sadistic, lazy and corrupt. The Turkish legal system likewise comes out of the film very badly. Even the warder's children are shown as being overweight and grotesque.

After interviewing all the protagonists behind the film, Sussman has concluded that Midnight Express was made with “no malice” or no intention to offend the Turks. “I can’t believe for one moment that was Alan’s motive,” she says of director Parker. “I think that was what you call an unintended consequence. I think they were creating what they thought was a somewhat loosely based story on Hayes’s life.”

When Midnight Express was released, it was credited with destroying the Turkish tourism industry almost single-handed and of poisoning relations between Turkey and the West. In the documentary, Parker stands by his work, but Stone expresses his regret at the misunderstanding that arose from the film.

In the documentary, Sussman, her husband and Hayes visit Turkey. Hayes discovers that he is still persona non grata. “He was very emotional being back in Turkey because he really loved Turkey and he always felt bad about its portrayal in the film,” Sussman says. “When he was back there, it was a chance for him to reassure Turkish people that ‘no. I don’t hate you’ …even if they hated him.”

When Hayes visited the places where he had been incarcerated, he had to be accompanied by plain clothes Turkish policemen for his own protection. He didn’t publicise his visit.

Midnight Return is screening in Cannes, just as Midnight Express did all those years ago, when Hayes attended the premiere – and met his future wife Wendy.

Did Hayes hide any marijuana in his socks when he was leaving Istanbul this time round? “He might have … but he didn’t tell me!” Sussman bursts into laughter at the question.

‘Midnight Return’ screens in Cannes this week

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks