Ghost in the Shell falls short of anime original

The film thrills but ducks the philosophical questions posed by a cyborg future

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How closely will we live with the technology we use in the future? How will it change us? And how close is “close”? Ghost in the Shell imagines a futuristic, hi-tech but grimy and ghetto-ridden Japanese metropolis populated by people, robots, and technologically-enhanced human cyborgs.

Beyond the superhuman strength, resilience, and X-ray vision provided by bodily enhancements, one of the most transformative aspects of this world is the idea of brain augmentation, that as cyborgs we might have two brains rather than one. Our biological brain – the “ghost” in the “shell” – would interface via neural implants to powerful embedded computers that would give us lightening fast reactions and heightened powers of reasoning, learning and memory.

First written as a Manga comic series in 1989 during the early days of the internet, Ghost in the Shell’s creator, Japanese artist Masamune Shirow, foresaw that this brain-computer interface would overcome the fundamental limitation of the human condition: that our minds are trapped inside our heads. In Shirow’s transhuman future our minds would be free to roam, relaying thoughts and imaginings to other networked brains, entering via the cloud into distant devices and sensors, even “deep diving” the mind of another in order to understand and share their experiences.

Shirow’s stories also pin-pointed some of the dangers of this giant technological leap. In a world where knowledge is power, these brain-computer interfaces would create new tools for government surveillance and control, and new kinds of crime such as “mind-jacking” – the remote control of another’s thoughts and actions. Nevertheless there was also a spiritual side to Shirow’s narrative: that the cyborg condition might be the next step in our evolution, and that the widening of perspective and the merging of individuality from a networking of minds could be a path to enlightenment.

Lost in translation

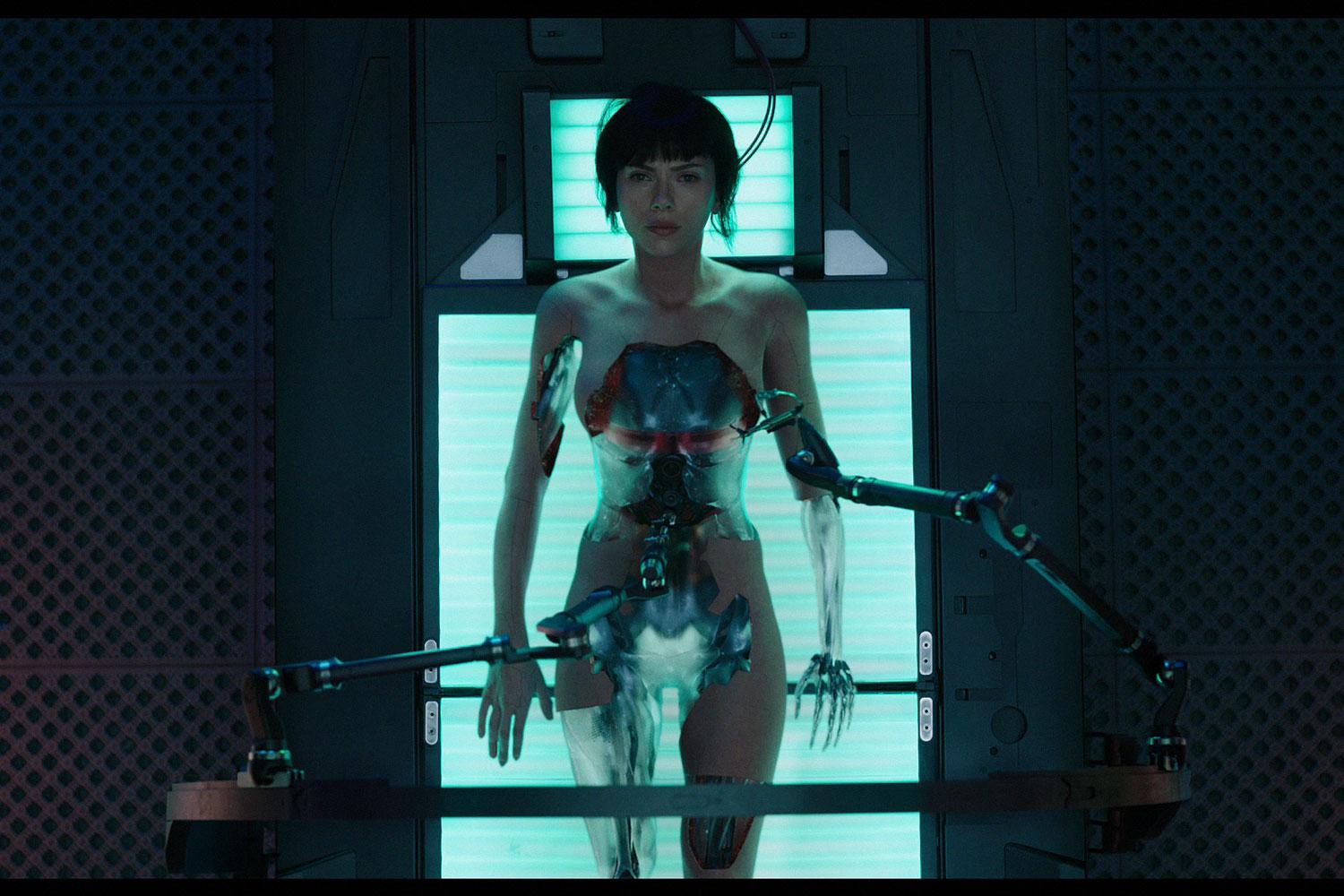

Borrowing heavily from Ghost in the Shell’s re-telling by director Mamoru Oshii in his classic 1995 animated film version, the newly arrived Hollywood cinematic interpretation stars Scarlett Johansson as Major, a cyborg working for Section 9, a government-run security organisation charged with fighting corruption and terrorism. Directed by Rupert Sanders, the new film is visually stunning and the storyline lovingly recreates some of the best scenes from the original anime.

Sadly though, Sanders’ movie pulls its punches around the core question of how this technology could change the human condition. Indeed, if casting Western actors in most key roles wasn’t enough, the new film also engages in a form of cultural appropriation by superimposing the myth of the American all-action hero – who you are is defined by what you do – on a character who is almost the complete antithesis of that notion.

Major fights the battles of her masters with increasing reluctance, questioning the actions asked of her, drawn to escape and contemplation. This is no action hero, but someone trying to piece together fragments of meaning from within her cyborg existence with which to assemble a worthwhile life.

A scene midway through the film shows, even more bluntly, the central role of memory in creating the self. We see the complete breakdown of a man who, having been mind-jacked, faces the realisation that his identity is built on false memories of a life never lived, and a family who never existed. The 1995 anime insists that we are individuals only because of our memories. While the new film retains much of the same story line, it refuses to follow the inference. Rather than being defined by our memories, Major’s voice tells us that “we cling to memories as if they define us, but what we do defines us”. Perhaps this is meant to be reassuring, but to me it is both confusing and unfaithful to the spirit of the original tale.

The new film also backs away from another key idea of Shirow’s work, that the human mind – even the human species – are, in essence, information. Where the 1995 anime talked of the possibility of leaving the physical body – the shell – elevating consciousness to a higher plane and “becoming part of all things”, the remake has only veiled hints that such a merging minds, or a melding of the human mind with the internet, could be either positive or transformational.

Open lives

In the real world, the notion of networked minds is already upon us. Touchscreens, keypads, cameras, mobile, the cloud: we are more and more directly and instantly linked to a widening circle of people, while opening up our personal lives to surveillance and potential manipulation by governments, advertisers, or worse.

Brain-computer interfaces are also on their way. There are already brain implants that can mitigate some of the symptoms of brain conditions, from Parkinson’s disease to depression. Others are being developed to overcome sensory impairments such as blindness or to control a paralysed limb. On the other hand, the remote control of behaviour using implanted brain stimulators has been demonstrated in several animal species, a frightening technology that could be applied to humans if someone were to choose to misuse it in that way.

The possibility of voluntarily networking our minds is also here. Devices like the Emotiv are simple wearable electroencephalograph-based (EEG) devices that can detect some of the signature electrical signals emitted by our brains, and are sufficiently intelligent to interpret those signals and turn them into useful output. For example, an Emotiv connected to a computer can control a videogame by the power of the wearer’s thoughts alone.

In terms of artificial intelligence, the work in my lab at Sheffield Robotics explores the possibility of building robot analogues of human memory for events and experiences. The fusion of such systems with the human brain is not possible with today’s technology – but it is imaginable in the decades to come. Were an electronic implant developed that could vastly improve your memory and intelligence, would you be tempted? Such technologies may be on the horizon, and science fiction imaginings such as Ghost in the Shell suggest that their power to fundamentally change the human condition should not be underestimated.

Tony Prescott is a professor of cognitive neuroscience and Director of the Sheffield Robotics Institute, University of Sheffield

This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments