Why 1939 was the greatest year in film history

Considered the peak of Hollywood’s Golden Age, with films devised primarily with movie stars and prestigious novels in mind, 1939 was a year of great cinema. Graeme Ross lists his Top 20 titles

On 7 April 1939, Samuel Goldwyn’s production of Emily Bronte’s famous novel Wuthering Heights was released, just one of 365 films produced in Hollywood alone in the year that many film scholars consider the greatest ever for cinema. It was certainly the peak for Hollywood’s Golden Age and the much maligned studio system ruled over by autocrats such as Louis B Mayer and Samuel Goldwyn.

Perhaps it was just serendipity that so many classics were released in 1939 or just the inevitable culmination of great art. Talkies had been established for a decade, with film techniques improving all the time, and European emigres were putting their own very personal stamp on directing and screen writing. And then there were the leading actors, of course, mostly discovered, nurtured and launched into superstardom by the studios and eagerly embraced by audiences who, in 1939 alone in the US purchased cinema tickets at a rate of 80 million a year.

Films were devised with the stars in mind and prestigious novels such as Wuthering Heights and blockbusters like Gone with the Wind would be purchased and filmed brilliantly with no expense spared. So, all these reasons and more contributed to a golden year for movies, and perhaps also there was a feeling even among the insular and self-absorbed of Hollywood that war was inevitable and things could never be quite the same again afterwards.

And so it proved post war, with the growing power of the stars themselves and the advent of television rendering the studio system that had been responsible for so many classics obsolete. Not surprisingly, European film makers had other things on their mind in 1939, but that’s not to say they aren’t represented on this list of the 20 best films of cinema’s greatest year. Try and watch as many of the 20 as you can.

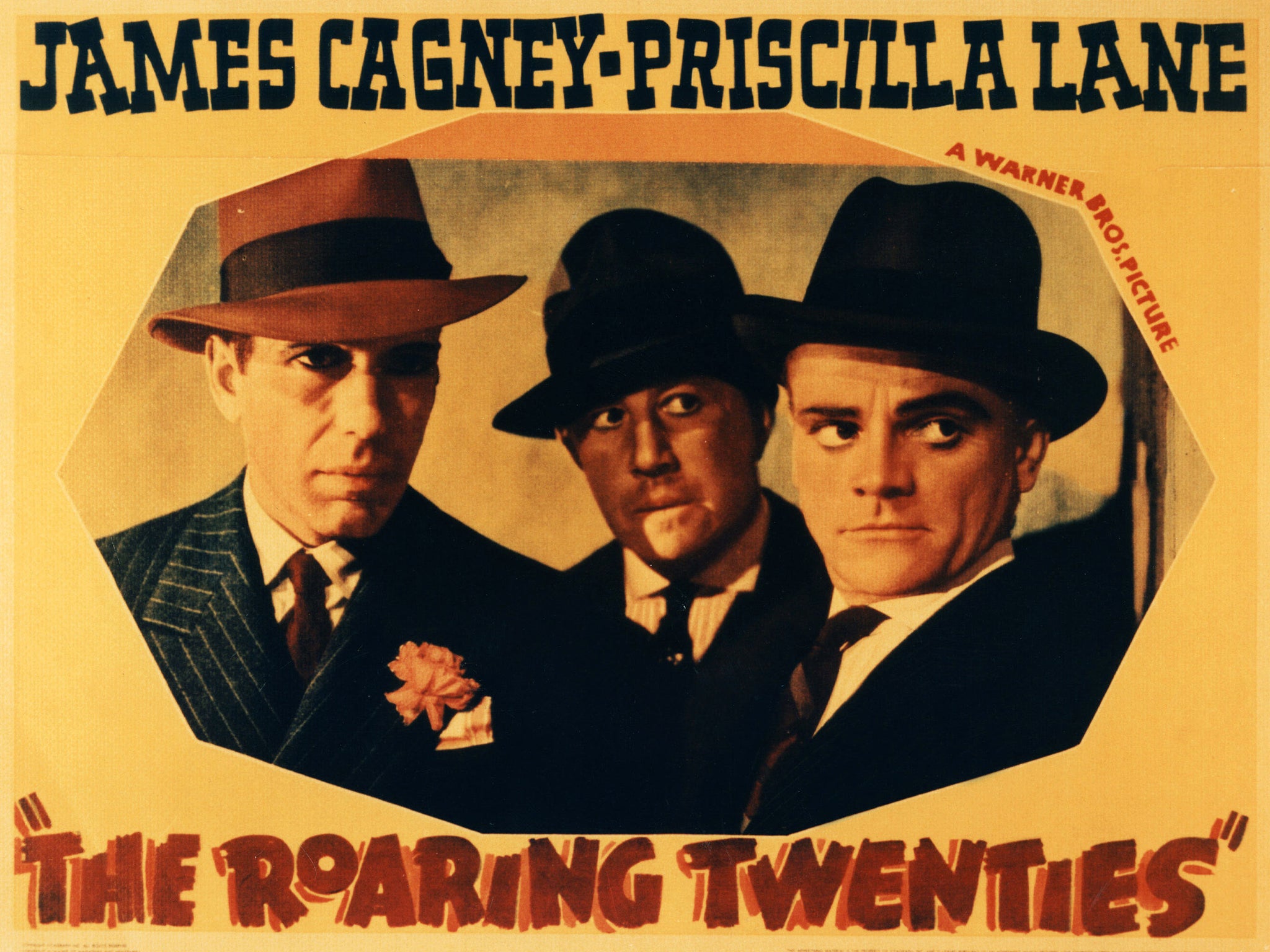

20. The Roaring Twenties (Directed by Raoul Walsh)

Quintessential James Cagney in a typical Warner Brothers gangster flick, which throws in some social commentary with Cagney as the disaffected war veteran who turns to crime when he can’t get his old job back after returning from the trenches. Not quite as essential as the previous year’s Angels With Dirty Faces, The Roaring Twenties has Humphrey Bogart in one of his pre-Casablanca bad-guy supporting roles too, but it’s Jimmy’s show all the way.

19. The Cat and the Canary (Dir Elliott Nugent)

The old dark house horror/comedy par excellence as a homicidal maniac stalks a group of people gathered together in an isolated mansion for the reading of a will. A young and fresh Bob Hope, beginning to hone his cowardly braggart persona, wisecracks his way through the thrills and chills as he protects the heiress in distress, Paulette Goddard. Best line? When asked, “Don’t big empty houses scare you?”, Hope replies, “Not me, I used to be in vaudeville.”

18. Dark Victory (Dir Edmund Goulding)

The definitive Bette Davis four-handkerchief weepie with the star earning one of her 10 Best Actress Oscar nominations for her role as the spoiled socialite dying from a brain tumour. Bogie is in this one too, miscast as an Irish stablehand, and a pre-Bedtime for Bonzo Ronald Reagan also. In other hands Dark Victory could be almost risibly maudlin, but with frequent Davis director Goulding at the helm and Warner Brothers’ grand production standards in full flow, this is peerless melodrama. And Davis is superb of course, giving perhaps the best performance of her career.

17. Midnight (Dir Mitchell Leisen)

One of the earliest examples of Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett’s wonderful writing partnership that would reach even greater heights after Wilder turned to directing. Claudette Colbert is superb as a penniless young women on the make in Paris who passes herself off as a countess, and Don Ameche also scores well as the taxi driver who falls for her. Many misunderstandings and complications ensue in one of the best of the 1930s screwball comedies which is full of Wilder’s soon-to-be signature tropes of deception and masquerade.

16. Gunga Din (George Stevens)

Hollywood Kipling which benefits from the great chemistry between Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen and Douglas Fairbanks Jr as the three sergeants battling each other and the murderous Thuggee cult in colonial India with the help of the courageous water carrier Gunga Din. Questionable racial attitudes and stereotypes aside, a glorious rollicking romp.

15. Destry Rides Again (Dir George Marshall)

James Stewart’s first western – he wouldn’t make another for more than a decade – was a lighthearted affair and all the better for it. Jimmy plays Tom Destry, the sheriff who prefers talk to gun play, prompting much derision in the wild town of Bottleneck. But there’s steel beneath Destry’s homespun philosophy and he tames the town despite the considerable distraction of a luminous Marlene Dietrich as the saloon madam Frenchy, memorably re-imagined by Madeline Kahn in Blazing Saddles. Dietrich still wows with her rendition of “See What the Boys in the Backroom Will Have”.

14. Young Mr Lincoln (Dir John Ford)

Henry Fonda was apprehensive about taking on the role but he needn’t have worried as he excelled as the future president. Highly fictionalised yes, but a typical slice of beautifully shot Fordian Americana, tracing Lincoln’s journey from poor country boy to fledgling lawyer fighting his first case.

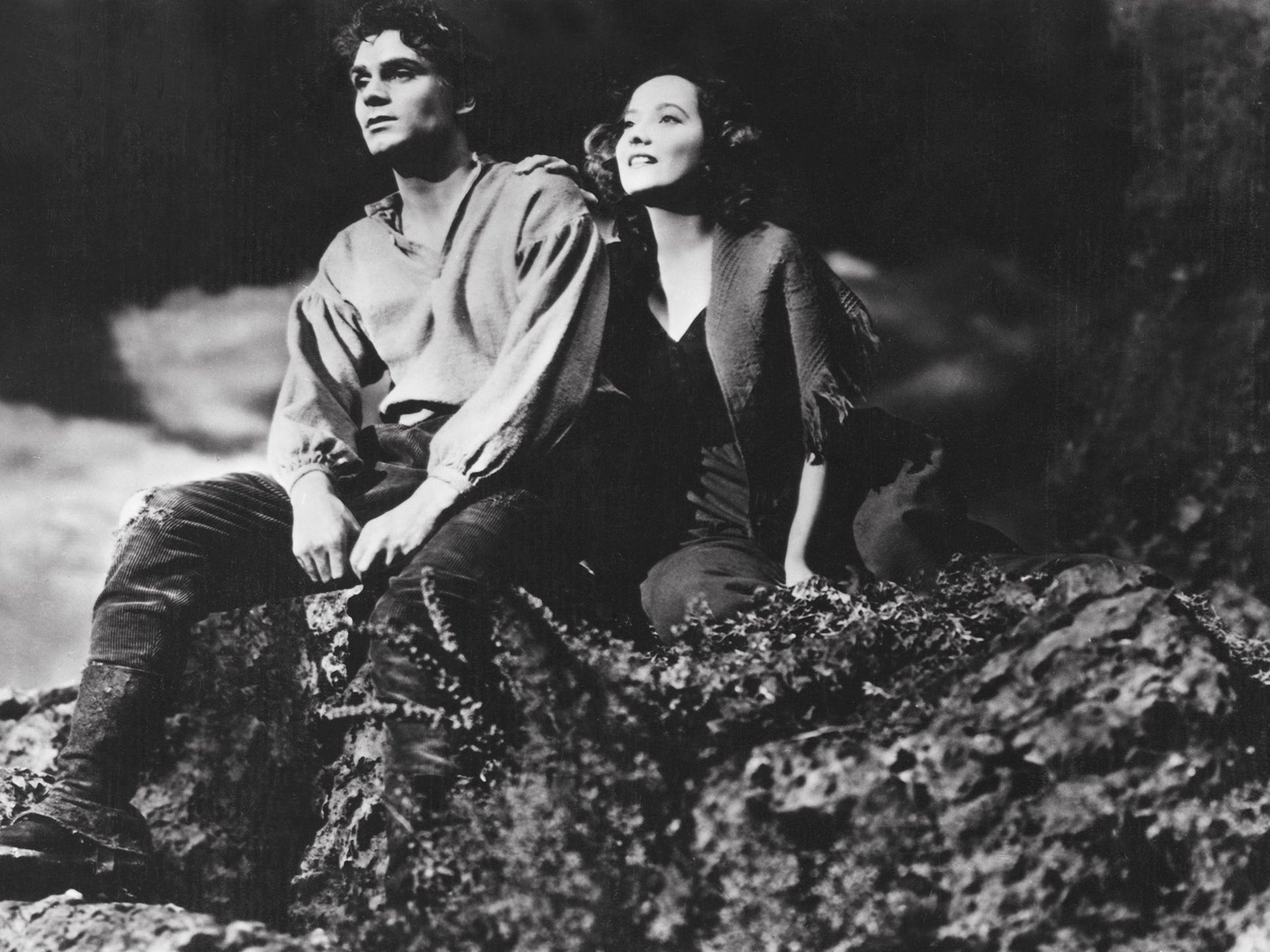

13. Wuthering Heights (Dir William Wyler)

Laurence Olivier became an international star for his smouldering Heathcliff and Merle Oberon won the part of Cathy despite Olivier’s objections (he wanted Vivien Leigh) in Samuel Goldwyn’s not entirely faithful (only the first 16 chapters were filmed), but typically lavish production of the famous novel. Director Wyler did all he could to keep the Goldwyn excesses at bay (apart from the tacked-on audience-friendly ending), and Gregg Toland’s Oscar-winning cinematography beautifully evoked Yorkshire’s windswept moors despite being shot in California. All in all, a perfect example of Hollywood’s craft.

12. The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Dir William Dieterle)

Charles Laughton came as close to a romantic hero as he ever did with his beautiful, sympathetic performance as the tragic bell-ringer Quasimodo. Lavish sets and Laughton’s extraordinary-for-the-time makeup contributed to the film’s huge budget and it remains the best adaption of Victor Hugo’s novel. When filming the bell-ringing scene news reached the set that Britain had declared war on Germany, and Laughton later said that he felt that he was ringing the bell for everyone who was going to be affected by the coming conflict.

11. Goodbye Mr Chips (Dir Sam Wood)

The only British film on this list (albeit under MGM aegis) is a deeply sentimental but undeniably affecting adaption of the James Hilton novella. With Clark Gable considered a certain winner for Gone With the Wind, Robert Donat upset the apple cart by winning the Best Actor Oscar for his role as Chipping, the initially unpopular schoolmaster at an all-boys private school who is transformed into a beloved institution by the love of a good woman (a radiant Greer Garson in her movie debut). You may baulk at the antiquated class system prevalent here, but as Chips reads out the roll of honour detailing all the former pupils who had died in the First World War, the realisation strikes that when Goodbye Mr Chips was released, the world stood on the very brink of another global conflict.

10. Of Mice and Men (Dir Lewis Milestone)

Lon Chaney Jr in the role he was born to play – Lennie, the sweet-natured, slow-witted giant who doesn’t know his own strength. Steinbeck’s powerful and moving novella was given the treatment and the performances it deserved with Burgess Meredith the very essence of Lennie’s protector, George – “every part of him defined”.

9. The Women (Dir George Cukor)

The ultimate women’s film directed by the ultimate women’s director. In an all-female cast (some 130 roles) some of the biggest stars of the era – Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, Paulette Goddard – bitch and catfight their way through New York’s high society with a superb, constantly amusing script offering trenchant comment on the mores of the so-called privileged classes.

8. Le joure se leve (Daybreak) (Dir Marcel Carne)

In 1939, not all the great movies were being made in Hollywood. Le joure se leve from acclaimed director Carne remains one of the most striking examples of French cinema’s Poetic Realism movement, with Jean Gabin giving one of his most memorable performances as the doomed protagonist who commits a murder, then waits in his hotel room for daybreak. The film’s brooding fatalism, incorporating flashback and femme fatale motifs, both anticipated and influenced the coming decade’s film noir genre.

7. Ninotchka (Dir Ernst Lubitsch)

“Garbo laughs!” ran the tagline for this perfect example of the famed “Lubitsch Touch”. And indeed she did, although it took an old-fashioned pratfall from Melvyn Douglas rather than the sparkling Billy Wilder/Charles Brackett script to melt the Ice Queen. In her penultimate film, Garbo demonstrated her flair for comedy as a humourless Russian envoy in Paris who initially resists western capitalism and the urbane Douglas, before succumbing to both.

6. Only Angels Have Wings (Dir Howard Hawks)

A Hawks classic incorporating his constant themes of male bonding, strong independent women, and getting the job done despite the odds. Cary Grant is the boss of a air freight company flying life-or-death missions over the Andes. The only way Grant and his pilots can cope is to adopt a superficial fatalism to the day-to-day dangers, but of course in typical Hawks style along comes Jean Arthur to stir the pot. It was a great year personally for one of Hollywood’s finest character actors, Thomas Mitchell, who featured in five films in 1939, all of them included here – this one, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and the next three on this list. He would lift the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for Stagecoach as the alcoholic Doc Boone.

5. Mr Smith Goes to Washington (Dir Frank Capra)

A tour-de-force performance from James Stewart in his breakthrough film as the idealistic, incorruptible senator who is given a rude awakening to the machinations and corruption of American politics. In a superb cast top-billed Jean Arthur also shines as the initially cynical political secretary who is won over by Stewart’s integrity, and who wouldn’t be after Stewart’s filibuster speech which has long since entered the annals of great movie memories. Stewart missed out on the Oscar but he would win it the following year for The Philadelphia Story. Depending on your viewpoint, Capra-corn or a perfect example of why we fall in love with movies in the first place.

4. Gone with the Wind (Dir Victor Fleming)

At almost four hours long, this legendary epic soap opera with a Civil War backdrop still doesn’t outstay its welcome, although it has fallen in critical favour in recent years. This is largely due to the film’s racial attitudes and sentimental view of slavery which have long been rightly condemned. So, it’s not the greatest film ever made, but arguably the most famous, a great spectacle and the the supreme example of how to film a blockbuster novel. The casting is pretty much perfect, with Vivien Leigh embodying the spoiled, headstrong Scarlett O’Hara and Clark Gable a smirking, roguish Rhett Butler, and the production values still astound. Winner of eight Oscars including Best Actress for Leigh, it’s still one of the highest box office earners ever, and an artistic triumph for the producer David O Selznick, whose vision it was.

3. Stagecoach (Dir John Ford)

The landmark western which, along with the same year’s Jesse James, reinvigorated and defined a genre which was in danger of sliding into B-movie oblivion. Part character study mixed with stirring action sequences courtesy of famed stunt man Yakima Canutt, Stagecoach made John Wayne a star and introduced many of the tropes that would become part and parcel of the genre, such as the cavalry riding to the rescue; but the most memorable and influential aspect is Ford’s use of Monument Valley, one of cinema’s most spectacular locations. Stagecoach didn’t just influence the development of westerns, however. Orson Welles was much taken by the cinematography, lighting and interior sets, as can be seen in Citizen Kane.

2. The Wizard of Oz (Dir Victor Fleming)

There are fine margins involved in making movie history. For example, would The Wizard of Oz have become quite so beloved if the sequence with the then 16-year-old Judy Garland singing “Over the Rainbow” hadn’t been reinstated after being cut from the final edit? Would it have been such a wonderful film if, as had been envisaged, Shirley Temple had taken the role of Dorothy? The Wizard of Oz also experienced a troubled shoot, with three separate directors input, although Fleming was given final credit. But there must have been some form of alchemy at large here, because the film is perfect in every way, with wonderful songs, visuals and performances and at 80 years old, is still the fantasy against which all others must be measured. A joyous experience from beginning to end, The Wizard of Oz is Hollywood’s greatest film of 1939, but not quite the greatest on this list.

1. La Regle Du Jeu (The Rules of the Game) (Dir Jean Renoir)

Banned, scorned, censored and butchered following its release, with the master negative destroyed in an air raid, it’s a miracle that this sublime comedy of manners exists at all. The fact that it does (courtesy of a full restoration 20 years after its original release) is cause to rejoice. Using the setting of a weekend party at an opulent country house, with aristocrats and lower classes alike indulging in various sexual shenanigans, Renoir trained his jaundiced eye on a dissolute French society tearing itself apart on the eve of the Second World War, but still adhering to their own set of rules, no matter how destructive. Poignant, extremely funny, much imitated, but impossible to replicate, The Rules of the Game is the greatest film of 1939, cinema’s greatest year.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks