Zalman King: The forgotten auteur who revolutionised sex, kink and female desire on screen

With his work on ‘9½ Weeks’, ‘Red Shoe Diaries’ and ‘Wild Orchid’, Zalman King introduced millions to new, erotic realms of cinematic pleasure. Kubrick also had him on his speed-dial. As ‘Wild Orchid’ turns 30, Adam White explores King’s forgotten legacy, and the collaborators eager to see him reappraised

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

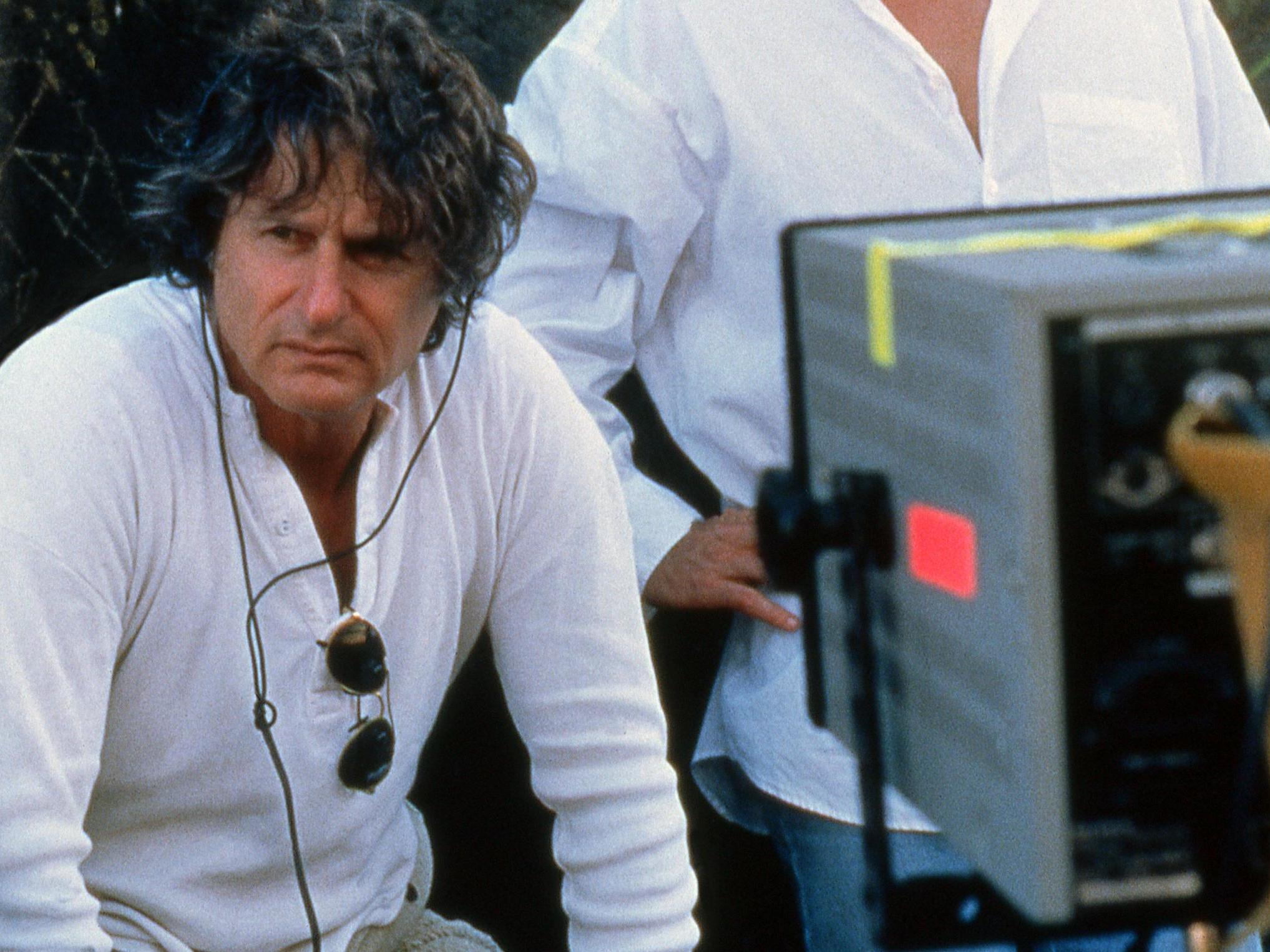

Your support makes all the difference.Stanley Kubrick needed to speak to someone about sex, so he called up the man who invented it. Through work such as 9½ Weeks (1986), the TV series Red Shoe Diaries and the Mickey Rourke vehicle Wild Orchid (1990), which turns 30 this week, American director Zalman King had cemented himself as a filmmaker of unusual and stirring sensuality. He didn’t quite invent the act of sex, of course, but he did shape the aesthetics of it on screen. When Kubrick was in pre-production on 1999’s Eyes Wide Shut, his erotic puzzleboard of a thriller, he knew exactly who to turn to for advice. They would speak every night for weeks on end.

“Kubrick loved how the men and women were portrayed in Zalman’s work,” author and screenwriter Elise D’Haene remembers. “He was calling to discuss how they shot women, how they cast women. He wanted to know how one approaches erotica as a filmmaker. I think within the industry there was a real respect and acknowledgement for everything that Zalman achieved. A lot of other people just wrote him off, which is really unfortunate.”

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, King’s spiritual home was the naughty aisle of the VHS rental store. There, his films became infamous, picked up with regularity by curious teenagers and men in long overcoats. Their cover art was uniform: women with their heads thrown back in ecstasy, their male lovers kissing at their necks. All sporting the same orangey red hue, like a thermometer come to life, the poster art was also somewhat misleading – despite indicating softcore pornography designed for and about men, King’s work was in fact largely about female desire.

King, who died in 2012 at the age of 70, came to cult renown alongside the speedy rise and fall of the mainstream erotic thriller. It was an era kickstarted by Basic Instinct (1992), dominated on home video by actor Shannon Tweed, the Meryl Streep of softcore, and plunged into a shallow grave by notorious flops like Sliver (1993) and Jade (1995). In those movies, men were perpetual dopes cursed by their libidos, all tragically preyed upon by volatile spider-women serving as harbingers of doom. As films, they swam in the same waters as King – borrowing his silk sheets, saxophone scores and arched backs in hazy light – but possessed none of the same erotic trill.

In truth, King was Hugh Hefner if he had gone to art school, a man fascinated less by narrative and sensation and more by mood. He would also, particularly in the case of Red Shoe Diaries, surround himself with female storytellers. D’Haene, Mary Lambert, Anne Goursaud and his wife, the late screenwriter Patricia Louisianna Knop, were among them, each helping grant his work the lived-in experiences of female desire.

“The story was sort of ephemeral,” remembers D’Haene, who scripted several episodes of Red Shoe Diaries. “You just entered this emotional, erotic realm. I think we want permission to be able to do that, you know? To go in and explore those aspects of ourselves, especially as women. Zalman’s work, and Patricia’s as well, allowed women to explore the power of their sexualities without shame – playing, pushing limits, going from total control to total abandon.”

“He didn’t ever look at it as being erotica,” adds King’s long-time editor Jim Bedford. “He wasn’t like, ‘Oh, I want to make erotic stuff’. He was interested in making things look gorgeous. He saw beauty, and that was probably the most important thing to him.”

A former actor, famous for being the first Jewish heartthrob on primetime US television, King transitioned behind the camera in the early 1980s. Patricia was an artist and screenwriter, and the pair lived together in a California home that was previously a brothel. They were otherwise conventional, and both in their fifties when they began writing erotic dramas.

The pair would first collaborate on the script for 9½ Weeks, which starred Kim Basinger as a buttoned-up art gallery assistant absorbed into a sadomasochistic affair with Mickey Rourke’s handsome stranger. It served as a blueprint for the rest of the King canon. There, burly strangers who look like Tarzan captivate reserved women, who bare their souls and their bodies. Masked balls play a recurring role, as do carnivals, circuses and cross-dressing; women who get off on toying with fragile men, women who adopt separate personas, or indulge in illicit acts away from the rigid confines of their friends and families. There’s plenty of voyeurism, too, King recognising the allure of the forbidden, and the indecent power of watching, waiting and pining.

In Wild Orchid, Carré Otis finds herself in a derelict mansion, where she spies a man ripping off a woman’s clothes, and watches from afar as the pair make passionate love under a burst water pipe. In Two Moon Junction (1988), Sherilyn Fenn showers off the chlorine from a dip in a public pool, and discreetly slips a tile from the wall. Behind it is a tiny hole connecting her cubicle and the gang shower on the other side, where two nude men, built like underwear models, wash themselves. In her nervous smile and glazed expression, you can tell she’s scared, aware that she’s watching a private act – yet she can’t pull herself away.

Red Shoe Diaries, the 1992 anthology series created by King and Louisianna Knop for the US cable network Showtime, is all about a man (played by David Duchovny) struggling to decipher the sexual fantasies of his dead ex. He places a call for sexual confessions in a local newspaper, with each episode opening and concluding with his awestruck narration as he reads from his latest correspondence – all tales of sexual exploration, kink and fantasy. Duchovny would film his bookend scenes in bulk whenever he had time off from The X-Files, while the tales themselves were acted out by recognisable faces: Matt LeBlanc, Ally Sheedy, comedian Margaret Cho, Sheryl Lee (aka Twin Peaks’s Laura Palmer). The casting sometimes provoked giggles (Joey Tribbiani rogering someone against a chain-link fence is never not funny), but they were otherwise genuinely steamy – showcasing sex in all its sudsy, messy and occasionally debauched glory.

“I really dislike the [word] softcore because a lot of people categorise my work as softcore, which I don’t see it as,” King said in 2006. “Softcore means softcore pornography, and that’s really not what I’m interested in. Eroticism has a real place in my vocabulary because eroticism usually needs to move out of a relationship or some sort of tension and that’s what I’m very interested in. I usually think of my work as romance.”

What made King’s work so mesmerising was its uncanny quality. His films didn’t so much exist but float. Watched in 2020, the likes of Red Shoe Diaries and Wild Orchid possess numerous visual signifiers of when they were made (specifically the shoulder-pads and abundance of velvet curtains), but they also seem to take place in a timeless netherworld – a sort of sexy dreamscape where nothing makes sense yet everything aches with carnality.

Siesta (1987), produced by King and scripted by Louisianna Knop, stars Ellen Barkin as a perspiring sky-diver left adrift in the Spanish desert. She wears a blood-stained red dress, encounters bohemian artists played by Jodie Foster and Grace Jones, and plunges head-first into reckless abandon. 1995’s Delta of Venus, inspired by Anaïs Nin’s short stories, is set in pre-Second World War France, yet also feels like an MTV pop video – time bends, scenes are cut together with sharp bangs and crashes, and every naked male looks like a Muscle Beach bodybuilder.

Those baroque and arguably confusing extremes, of sincere eroticism and outlandish fantasy, could explain why King never earned enormous critical respect in his lifetime. King and Louisianna Knop were popular in Hollywood, with an eclectic social circle that included Bernardo Bertolucci, Barbra Streisand and Annie Lennox, but their work itself was often jeered at by outsiders.

Despite being one of the most singular and lucrative filmmakers of the 1990s, King would become shorthand in critic spaces for overblown, softcore trash. “Zalman King takes credit for writing and directing, and no one is fighting him for it,” wrote the New York Times in their review of Two Moon Junction. “He’s made nothing but bad movies,” wrote the Los Angeles Times in 1992. Those that worked with him tell a different story.

“He was a real filmmaker,” Bedford recalls. “He was making films he wanted to make. He wasn’t out there trying to make erotica to exploit a market. Not only did he make films that he took very seriously and were beautiful to watch, there were definitely some things in them that were very, very good. He passed away right before the Oscars and they didn’t mention him at all. I thought that was disappointing.”

“I’ve worked with a lot of people that get respect and they weren’t the artist that Zalman was,” David Duchovny told Entertainment Weekly upon King’s death. “I use the word artist reservedly because it’s thrown around, like genius, way too much. But that was his soul. That’s the place where he came from. I don’t think people understand that. They say this or that about Red Shoes or whatever, and they pigeonhole him in that [erotica] area but it’s not who he was. He was way more concerned with the colour of the drapes than showing any T&A.”

Outside of 9½ Weeks, for which director Adrian Lyne received much of the kudos, King’s other work has been relegated to throwaway examples of softcore nostalgia. Even Wild Orchid, arguably the most hypnotic and striking of his films, is now only really known for the on-set urban legend it sparked: that Otis and her co-star Rourke, who would embark on a volatile and well-publicised marriage in its aftermath, had real sex on camera. Both have denied the claim.

Following 1995’s Delta of Venus and the end of Red Shoe Diaries in 1997, King would work only intermittently – on web series, unaired TV pilots, and erotica with far smaller budgets. “I think at that point, maybe because there was so much pornography out there, people watched other things instead,” Bedford suggests. “It’s like how Playboy went out of business – there was stuff available that was so much more extreme than what he was doing.”

D’Haene hopes a much-mooted revival of Red Shoe Diaries, which would be spearheaded by King’s daughter Chloe, will remind audiences of King’s importance as a visionary – and the many women he recruited to work on the original series.

“I think the cultivating of female voices was groundbreaking,” she says. “I think that’s why the series was so popular among women. Men watched it as well, of course – I can’t tell you how many guys come up to me and go, ‘Oh my god, Red Shoe Diaries helped me with my sexuality when I was 13!’ – but I think it was the women’s voices that really set it apart. It opened up a whole exploration of women and their point of view. You look at something like Fifty Shades of Grey and how crazy successful they have been – for me, though, they can’t hold a candle to Zalman’s work.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments