Strikes! Camera! No action – how the writers’ strike changed Hollywood forever

The identity of Tom Hanks has been stolen by a deep fake, robots are coming for ‘red carpet’ jobs and it could even be curtains for the Oscars as we know it. The writers’ strike may be over, says film critic and producer Jason Solomons as the London Film Festival opens, but the drama is still playing out on our screens

Imagine the scene. A Hollywood evening heavy with traffic and anticipation. Lucky ticket holders craning their necks on the bleachers. TV presenters readying their mics and the world’s photographers checking their camera batteries as they wobble on their stepladders in excited expectation. A limo pulls up and, after all the fittings and grooming, its passenger steps out with their bravest smile on to face the frenzy... only to be met with a collective sigh of: “Nobody.”

Unless Hollywood gets back to work making movies, it’s what could happen in March – an Oscars with no stars, a red carpet with no stardust. Sure there will be the odd director you might have heard of, or even recognise (Martin Scorsese, Greta Gerwig and... is that Christopher Nolan?) but a struck Oscars would be nothing short of a disaster. Frankly, it wouldn’t be the Oscars at all.

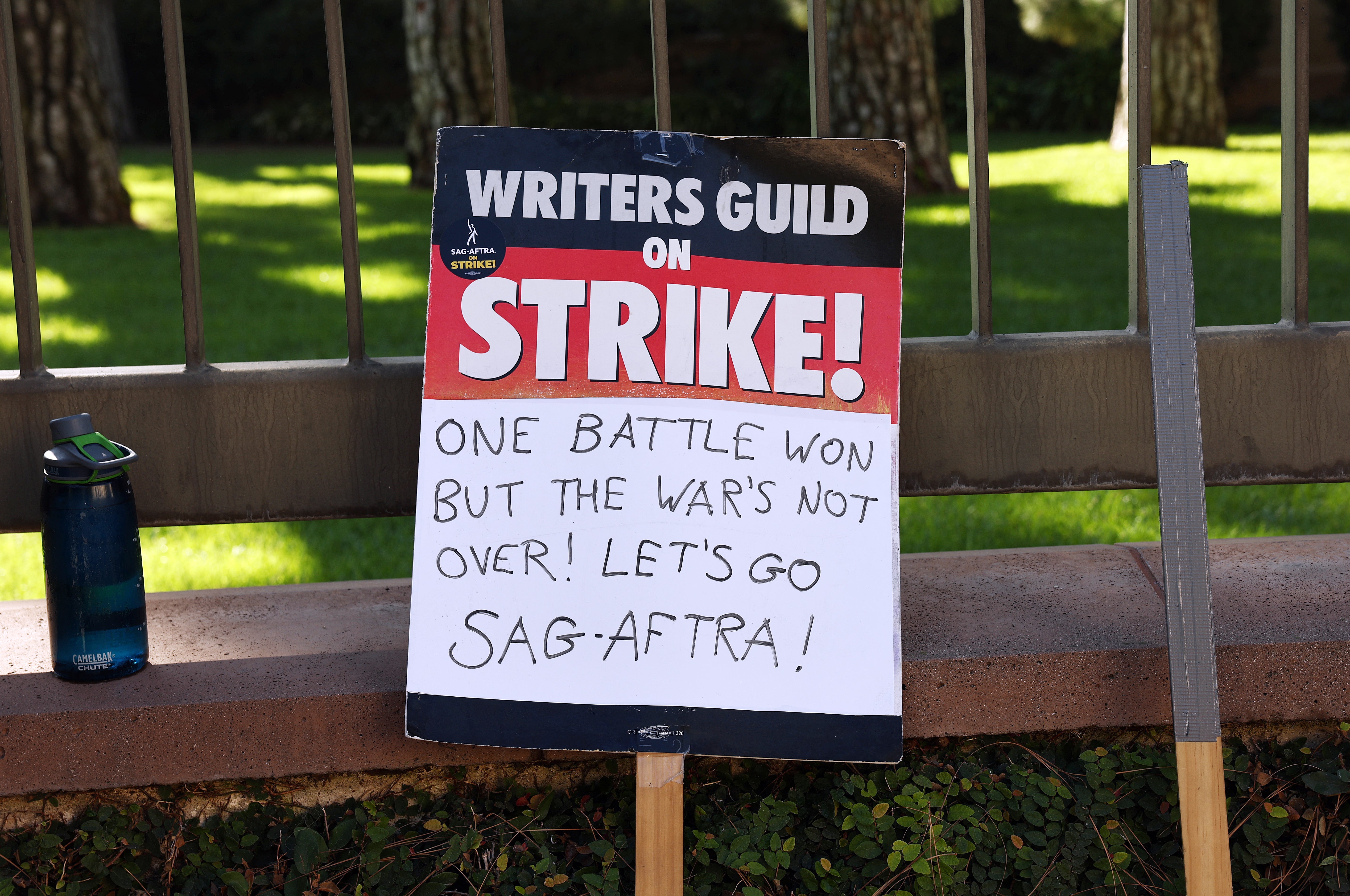

We might not get there. But after a distinctly unstarry season of festivals such as Venice and Toronto, and a London Film Festival kicking off this Wednesday (4 October), it’s possible. The good news is that striking actors are back at the tables. Not the roundtable interviews so prevalent at this time of year, but the negotiating tables, given fresh impetus by last week’s resolution of the Hollywood writers’ strike after 146 days of picket lines and protest.

To many outside the film industry, these strikes might seem like a distant dispute among wealthy individuals in the Hollywood Hills. However, their impact has been painful, and far reaching, disrupting movie releases, Netflix streams and your favourite TV show. It might not be immediately obvious to you yet, but for many of us working in the industry it has been alarming how quickly everything has ground to a halt.

Last week it was announced that the writers’ strike had finally come to an end as the Writers’ Guild of America (WGA) had successfully negotiated an agreement securing “meaningful gains and protections” for its 11,500 members with the studios and streaming platforms. But the storm clouds haven’t abated. The creative industries union BECTU is organising a rally in Leicester Square this Thursday (5 October) to raise awareness of the impact the US strikes have had on UK film and TV workers. Meanwhile, Hollywood is facing the ongoing headache of a 150,000-member-strong actors’ union, SAG-AFTRA, still being on the picket line. So, even if words do flow back on the page, there risks no one being around to speak lines to the camera.

The intricate Jenga of the international film and TV production community and their challenges may seem insignificant in a world grappling with war and climate change. Yet, as a film critic and first-time producer, I’ve found it heart-wrenching to see all this turmoil in an industry meant to entertain and inspire.

Since George Lucas’s Star Wars in the 1970s, Hollywood has extensively utilised UK studios and crews, establishing the UK as a prime location for film and TV production. The TV industry alone contributes £3.9bn to our economy, with production facilities accommodating the insatiable content demand from streamers like Netflix, Disney, and Amazon. It has meant that huge productions such as Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, Barbie and the latest Mission Impossible movies have all been shot on our stages. But these vast spaces have been frozen over for months.

“They’re like ghost towns,” one producer scouting locations and visiting Pinewood told me last week.

The UK’s thriving visual effects industry, known for groundbreaking work in films such as Gravity, Dune and Oppenheimer, reported a loss of around 40 per cent of its workforce during the strikes, equating to roughly 4,000 lost jobs out of 10,000. A survey conducted by BECTU revealed that 75 per cent of its members were no longer working, encompassing a wide range of film and TV professionals, from camera operators to costume designers.

“It highlights what a fragile industry we are,” one prominent UK producer involved in a Hollywood production told me, admitting to feeling powerless to help those on her huge team. “They have mortgages to pay and almost no one is working. And there’s nothing I can do to help them. Coming right after the pandemic, it’s a terrible time of uncertainty.”

How did this situation arise, where the actions of a writers’ room on a late-night US TV talk show can have such an impact on the life of a set dresser in Clapham, a graphics compositor in Liverpool and a camera operator in Brighton?

The writer’s strike was, in essence, a response to the changing landscape of the entertainment industry due to the rise of streaming platforms such as Netflix and Disney+. While these platforms offered numerous new opportunities, the new business model introduced uncertainties. Traditional films had clear stages: cinema release, DVD release, TV broadcast, and residual payments. However, in the streaming era, traditional box office figures and unit sales no longer apply, with most companies withholding viewing figures even for their most-watched output.

Writers protested they were not being fairly compensated for their work, and that the deal that has been struck was “exceptional” in that it delivered on most of the unions’ demands around payment for streaming content and protection against AI encroaching on writers’ credits.

People have mortgages to pay and almost no one is working... It’s a terrible time of uncertainty

However, while members of the Writers Guild may be doing a victory lap, they are still to be joined by thousands of production staff currently out of work and actors waiting for their own resolutions. The dispute has also pulled into sharp focus just how upended the industry has become with the arrival firstly of streaming and, secondly, of AI, which, despite the recent concessions, remains an existential threat.

On Monday, Tom Hanks sent up a flare, warning his 9.5 million Instagram followers that an ad for a dental plan had used an AI-created image of him without his permission. He joins many other actors who are increasingly worried about how AI will threaten their future. Hanks told comedian Adam Buxton’s podcast in April, “I could be hit by a bus tomorrow, and that’s it, but performances can go on and on... there’ll be nothing to tell you that it’s not me and me alone. That’s certainly an artistic challenge, but it’s also a legal one.”

As a critic, I am accustomed to quickly reviewing and moving on to the next project. For years, directors would tell me it had taken them five, or seven, sometimes even 10 years to get their movie made and I’d be baffled as to how anyone would want to work on something for so long. But now, attempting, as I am, to make a film for the first time, I have a new sympathy for anyone trying to get anything in this delicate ecosystem. Hollywood’s famous adage, “No one knows anything,” has never been truer than now.

In my experience as a first-time producer, an American director initially attached to my film, A Waiter in Paris, had to step down due to the strike’s disruptions. Finding a new director who was an American resident in Europe allowed us to circumvent the writers’ union’s jurisdiction. However, it remains uncertain when we can begin discussions with actors. Producing is filled with daily dramas at the best of times, but the current situation feels like an epic.

Last month at the Venice Film Festival, few could ignore the lack of razzle-dazzle typically associated with the late summer event that kicks off awards season. Streamers such as Netflix – billed as ‘struck companies’ by SAG-AFTRA rules – were there in force, showing off their high-profile, award-ready products such as Leonard Bernstein biopic Maestro and hitman thriller The Killer, but there was no Bradley Cooper, Carey Mulligan or Michael Fassbender to support them. I’ve never seen a red carpet so clean and untrodden – DEARTH IN VENICE ran one smart headline. It proved a red carpet really is just a red carpet if there isn’t enough sparkle sprinkled on it.

The London Film Festival, opening this week, will still showcase impressive films such as Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn, starring Rosamund Pike, the Venice winner Poor Things with Emma Stone and hot ticket All of Us Strangers, starring Andrew Scott and Paul Mescal. All will be playing to packed audiences on the Southbank, and to awards voters from Bafta and the Academy, but with so many actors on strike and staying away out of solidarity, the red carpets along the river at the Royal Festival Hall will be significantly less worked than usual.

The actors’ strike, ongoing since 14 July, may extend up to the Oscars in March 2024 if their demands, focusing on image rights, likeness, voice work, special effects and background work are not met. While there is enough quality film in the pipeline for next year’s Academy Awards to go ahead, longer delays in returning to work could well mean there’s no one to present the show or accept the biggest awards in the acting categories. Further along, a lack of big films in the following 2025 voting corridor could be disastrous. It’s becoming a game of chicken at this point, to see who can hold out.

And, initially a footnote, AI has now become the most significant concern for almost everyone. The Writers’ Guild of America agreement addresses AI’s use and specifies that AI cannot “write or rewrite literary material” or be considered “source material”. This safeguards writers’ credits and rights. And noting that this strike was essentially the first workplace battle between humans and AI, the LA Times boldly declared: “The Humans Won”. But have they really?

A key point in the writers’ settlement was the language around the use of AI, which many writers fear can replace them in the development and production process. There’s a stage in the development of every movie called “budget and schedule”, for which a producer will hire an experienced “line producer” who will go through the script line by line and work out how much each scene will cost to shoot and how long it will need for the whole film to be shot. This can usually cost you a few thousand quid – last week, I was shown an AI programme that did it in five minutes, for free.

AI can replicate actors’ likenesses, potentially eliminating the need for background artists. There are now services that provide human-sounding AI narrators to publishers, meaning voiceover actors will no longer be needed. There are whole websites available with databases of voices for video games and animation. Ultimately, we are now having to ask big questions around the essence of creativity itself. While some new guardrails have been put in place, in this new tech dawn, it is impossible to know many roles algorithms will replace. As one person commented last week, when it comes to renegotiating the deal three years from now, there is always the possibility that studios will turn around to its writers and say: “Thanks, but no thanks, we’re done.”

The film I’m producing, an adaptation of Edward Chisholm’s book A Waiter in Paris, tells a unique story filled with personal experiences, emotions, and authenticity. I was tempted to see what AI could do, and so I tried it. The plot and dialogue that it came up with was terrifyingly OK, a bit like an episode of Emily in Paris. I quickly shut my laptop to avoid peering deeper into the abyss. I’m still committed to the traditional approach and think AI struggles to capture the complexity of human experiences and the unique elements that make a story original and compelling. Can AI tell jokes and capture the emotional nuances that make the best movies memorable? Not now, but one day maybe.

Alex Tate, a writer and producer who has worked in Hollywood and the UK, believes this is the first step to AI finding its place in the system. “Over the last couple of years, I’ve started to hear so many horror stories – actors being offered measly sums for the use of their likeness in perpetuity, and creatives going into meetings and where commissioners refer to the algorithm that not only set up the meeting that’s called them in, but also has already picked out the specific story, budget and cast it wants.

The strikes have shown that everyone in the film and TV ecosystem is interconnected

“But all new tech comes in like a clumsy foal smashing into things until it eventually understands itself, and we harness it,” he says. “I like to say, it’s a fight to get what you deserve but getting what you deserve is worth the fight.”

In the end, it comes down to whether audiences and creators value the emotional and human aspects that define great films. The strikes have shown that everyone in the film and TV ecosystem is interconnected, from studio heads to streamer tycoons, from red carpet stars to independent producers and the diverse army of workers who bring a writer’s story to life.

“It’s been terrible, no doubt about it,” reflects Adrian Wootton, CEO of Film London and the British Film Commission. “But we are expecting a feeding frenzy when it all starts up again and the UK is in the best position to benefit from that.”

Making a movie takes a village, and the strikes have underscored an industry grappling with change. As the immediate focus, rightly, is getting people back to work, the battle to ensure the soul of creativity is likely to be long and hard fought. We all have to hope, to trust, that audiences, producers, financers, studio executives and actors still care about the emotional beats and rough edges that make the best movies. You know what I mean, when watching them makes us feel just that little bit more alive and human.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks