‘I am older than her father’: How ‘Manhattan’ anticipated Woody Allen’s behaviour

On the 40th anniversary of its British release, the story of a middle-aged man dating a 17-year-old gives viewers a jolt, writes Geoffrey Macnab

Woody Allen’s Manhattan is, according to one influential critic, “the only truly great film of the Seventies”. It picked up Oscar nominations and was chosen for preservation in the US National Film Registry, an honour reserved only for movies of the greatest “cultural significance”. It is revived frequently – or, at least, used to be – and this week marks the 40th anniversary of its original British release. And yet nobody is banging drums to remind the British public of that fact.

Allen has been in the news in the past few weeks – but not because the press wants to talk about one of his greatest films. The focus of recent media attention has been on the 83-year-old’s apparently longstanding friendship with Jeffrey Epstein, the wealthy financier who died in his Manhattan prison cell on 10 August while awaiting trial on sex trafficking charges involving underage girls.

Allen has been in San Sebastian recently, away from the Epstein din, filming his latest comedy, Rifkin’s Festival, starring Gina Gershon and Christoph Waltz, and which is set during the city’s annual film festival.

At a press conference last month, the day before the European-financed film began shooting, Allen was in stoical form, saying that his philosophy ever since he started in show business has always been to “keep focused on the work”. No matter what happens in his private life, he insisted, he would carry on writing and directing.

Allen is one of the most prolific and revered film directors of his era, but it is obvious that his stock has fallen very sharply. Amazon Studios refused to release his most recent film, A Rainy Day In New York, and cancelled its multimillion-dollar movie deal with him last year after a steady drip of negative stories about him. Old allegations of molestation against his adopted daughter Dylan Farrow had resurfaced in the media – allegations that he had always denied – after Farrow reiterated them in a letter to The New York Times. Actors queued up to express their regret about working with him. Old friends turned on him. Those who defended him, like Kate Winslet, were attacked for doing so.

Lovers of Allen’s work might get a jolt when they watch Manhattan now. The brilliance of the filmmaking remains undimmed. The opening scenes, in particular, are beautiful. We hear the familiar, magical strains of “Rhapsody in Blue” as Allen begins his voiceover extolling his home city. “Chapter One. He adored New York City. He idolised it all out of proportion … to him, no matter what the season was, this was still a town that existed in black and white and pulsated to the great tunes of George Gershwin.”

Cinematographer Gordon Willis shot the film in widescreen black and white. Every frame of the opening Symphony of a Great City-style sequence is as artfully composed as any Magnum photograph. Under Willis’s eye, images of traffic jams or of washing hanging outside brownstones seem lyrical and alluring.

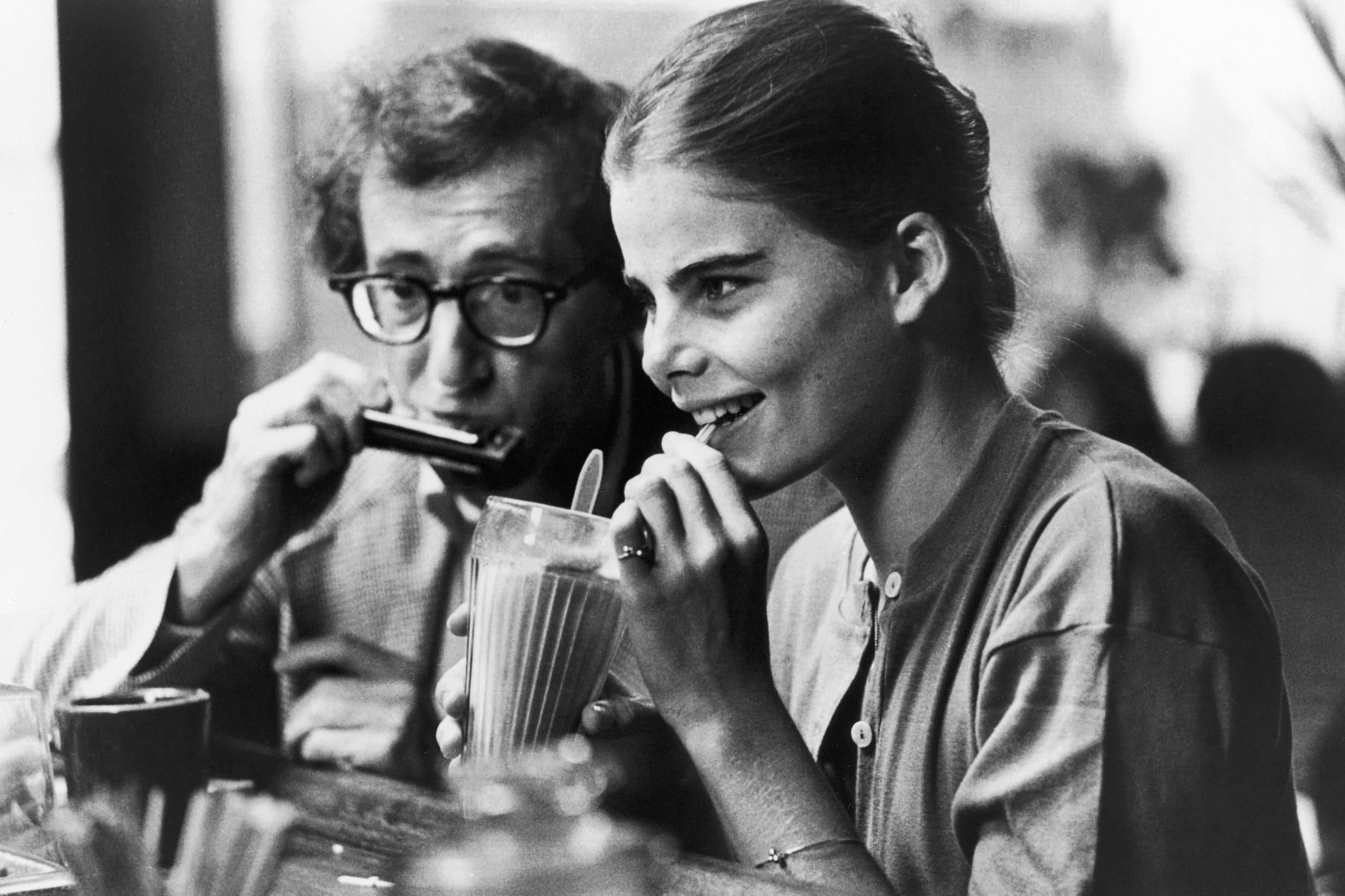

Once the overture is complete, we are introduced properly to Isaac Davis (Allen’s character). Here, contemporary viewers may begin to feel just a little queasy. Isaac is first seen in a restaurant with his girlfriend Tracy (Mariel Hemingway) and his friends Yale (Michael Murphy) and Emily (Anne Byrne Hoffman).

“She’s gorgeous!” Yale enthuses after Tracy excuses herself to leave the table.

“She’s 17,” Isaac immediately replies. “I am 42 and she is 17. I am older than her father.”

Back in 1979, the relationship between the middle-aged TV comedy writer and the teenager still at school provoked little comment. In his book of interviews with Allen, Swedish author Stig Björkman didn’t even mention it. But in 2019, that relationship seems strange and exploitative. Tracy is 17, but it is clear she and Isaac have been in a relationship for some time. How did they meet? How old was she then? These aren’t questions the film addresses.

Hemingway was 16 when she filmed Manhattan, and had never kissed anyone before. When it came time to film her kissing scene with Allen, she later said, “He attacked me like a linebacker”. Two years later, according to her memoir Out Came the Sun, Allen pursued her, inviting her to join him on a trip to Europe.

Ironically, Hemingway’s Tracy is the most grown-up figure in the film. She has none of the neuroses, grudges or the petty malice of Isaac and his friends like Yale and Mary (Diane Keaton), or his lesbian ex-wife, Jill (Meryl Streep), all of whom blithely betray one another and gossip relentlessly.

“Manhattan testifies with eloquence and candour that Allen also may have a soft spot in his heart for young, young women,” journalist Natalie Gittelson suggested in a profile of Allen written for The New York Times when Manhattan was released. “But there is little of [Lolita’s] Humbert Humbert here. Although sex is by no means devalued, the real attraction lies between kindred spirits.”

The title of her article, The Maturing of Woody Allen, was revealing. She cited Manhattan as evidence of Allen’s “ever-deepening personal vision and his growth as an artist”. He had, she suggested, now “shed his adolescent insecurity”.

Forty years on, such a verdict seems way off beam. Allen’s adolescent insecurity is foregrounded in almost every scene of Manhattan. It’s the source of much of the comedy. The idea that Isaac and Tracy are simply kindred spirits whose love for one another transcends sex and the generational divide is far fetched in the extreme.

The script for Manhattan was co-scripted by Marshall Brickman. Allen later claimed in an interview that the affair between “the older guy and the younger girl” was regarded by the writers as simply a “rich area to get comic scenes in”, a “good laugh gimmick” and a “good romantic gimmick” that had no relation to his life at that time. Allen’s work, though, has always been viewed through the prism of his own life. In spite of his continued protests to the contrary, critics and audiences have long assumed that the character they are watching on screen is a close facsimile of the real Allen. When he began a relationship with (and subsequently married) his ex-wife Mia Farrow’s adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn, who was 35 years younger than he was, it was inevitable that Manhattan would be looked at again. The film seemed to anticipate his later behaviour.

The actual model for the Mariel Hemingway character appears to have been Stacey Nelkin, a 17-year-old actress with whom Allen had an affair during the making of Annie Hall (1977). She has always defended Allen and dismissed the criticism of him as “abominable”.

“It was a life-altering relationship,” she told CNN in 2014. “He taught me many, many things. He was a father figure to me as you can imagine of somebody 24 years older and it was a wonderful relationship … he taught me all kinds of things about film and music and life. He was a wonderful man and we had a great time.”

The days are long gone when the only persistent criticism of Allen’s films was that they presented New York in a blinkered, make-believe way, and that he failed to acknowledge the ethnic diversity of the city.

“Woody Allen, he can do a film about Manhattan – it’s about one-half black and Hispanic – and he doesn’t have a single black person in the film,” Spike Lee famously complained about his fellow director.

Now, the controversy about Allen’s work is less to do with the films themselves than with Allen’s public reputation, his family life and his ill-judged remarks about the Harvey Weinstein scandal and the #MeToo movement. “You don’t want it to lead to a witch-hunt atmosphere, a Salem atmosphere, where every guy in an office who winks at a woman is suddenly having to defend himself,” Allen remarked when the scandal broke. He was accused of failing to grasp “the gravity of the issues or the implications for his own career”.

The paradox is that Allen’s films have given glorious roles to many actresses. Cate Blanchett deservedly won an Oscar for her role as the Blanche Du Bois-like socialite trying to cling to her dignity and her sanity in Blue Jasmine (2013). Kate Winslet gave a searing performance in Wonder Wheel (2017) but the film was spurned, at least partly because Allen expressed sympathy for the disgraced Weinstein in the lead up to its release.

Manhattan has wonderful performances, too. Keaton is brilliant as the endearingly narcissistic Mary, forever switching lovers and forever reminding everybody that she comes from Philadelphia; Streep is funny and acidic as Isaac’s estranged wife, while Hemingway has a touchingly ingenuous and trusting quality as his far too young lover.

There is a revealing moment towards the end of the film when Isaac is shown talking to his philandering professor friend, Yale, while standing next to a skeleton. “What are future generations going to say about us,” Isaac whines. “It’s very important to have some kind of personal integrity. I want to make sure that when I thin out I am well thought of.”

If Allen shares these sentiments, he must be mortified about the bruising that his reputation has already taken during his own lifetime. Watching Manhattan again is to be reminded his films have aged much better than he has.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks