Wim Wenders on Beyoncé’s tribute to Paris, Texas and how Tokyo toilets inspired his new film

The German auteur has been Oscar-nominated for ‘Perfect Days’. He talks to Kevin E G Perry about the meaning behind the film, dropping Columbo into Cold War Berlin and how he ended up in a fashion show in front of Zinedine Zidane

Wim Wenders’s new film Perfect Days is perhaps the only Oscar nominee in history to be based on a series of Japanese public toilets. Just when you thought we’d exhausted every conceivable type of intellectual property, here comes the German auteur to offer a whole new definition of IP. In 2022, Wenders was approached by the Tokyo Toilet art project, which had commissioned leading architects and designers to create 17 toilets spread across the city’s fashionable Shibuya district. They hoped Wenders might make a documentary about their sparkling new facilities. Instead, he envisioned a simple drama about a man who cleans them.

We get to know Hirayama (Koji Yakusho) through his daily routine: the toilets he cleans thoroughly and methodically, the public baths where he does the same to himself, and the frequent commutes where he listens to his favourite music on cassette tapes that intrigue and baffle the film’s younger characters. These tapes are the key to unlocking his character, so when Wenders decided to open the film with Hirayama sliding in a battered cassette of The Animals’ eerie 1964 recording of “The House of the Rising Sun”, he worried it might not be the right choice.

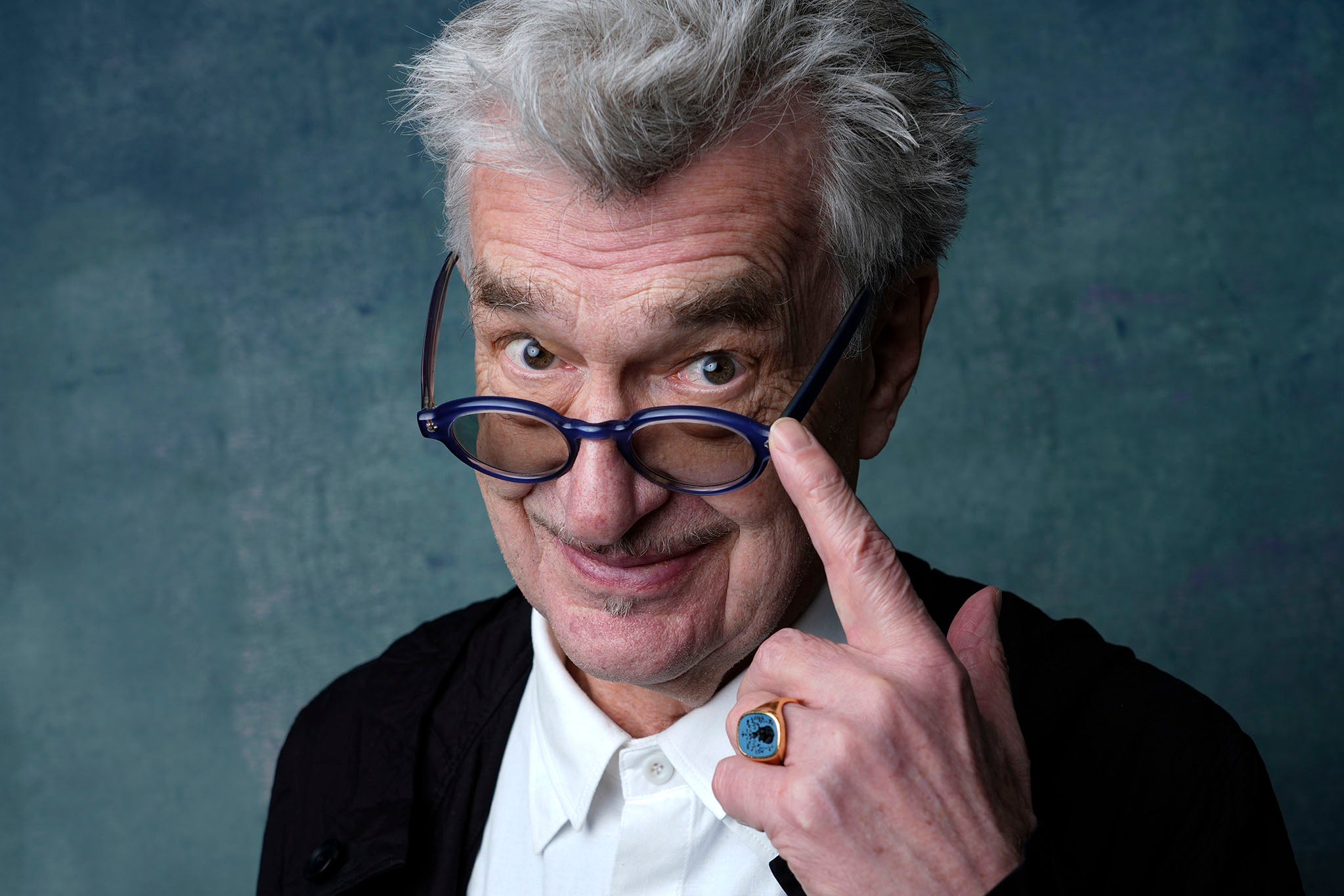

“I felt I was imposing myself, and that this was cultural appropriation,” says the grey-haired 78-year-old thoughtfully from a hotel room in London, eyes twinkling behind blue-framed glasses. “I said, wait a minute. This is a Japanese character a few years younger than me, can I impose my musical taste? This is not a good thing!”

His co-writer, Takuma Takasaki, soon set Wenders straight. “Oh, this is a misunderstanding,” the 54-year-old movie producer told him. “We didn’t listen to anything different than you did. You must know that Ry Cooder gave his greatest concert in Tokyo! Don’t try to find out what taste Hirayama has. He has the taste of his generation, and his was a global generation.”

Music – drawn from all around the globe – has always woven its way through Wenders’s films. His 1984 Palme d’Or-winning road movie Paris, Texas featured a spellbinding slide guitar score by Cooder, and has proved so enduringly influential that Beyonce references the film and Harry Dean Stanton’s red-capped drifter Travis in the teaser for her latest single “Texas Hold ’Em”. “Wow! Who’d a thunk it, that Travis on his long way home to Paris, Texas would turn out to be a Beyonce fan!” Wenders emails me later, after the video appears online. “With a bit of luck at the poker table, it might turn out to be a perfect day!”

Wenders followed his breakthrough film with another masterpiece, Wings of Desire, which featured angels hanging out at Nick Cave gigs in West Berlin. He has often made musicians the subject of his documentaries, most famously collaborating with Cooder again on 1999’s Havana-set Buena Vista Social Club. Perfect Days continues the theme. Its title nods to the Lou Reed song, which appears on the soundtrack along with classics by other Wenders favourites, including The Kinks, Van Morrison and Nina Simone. “We defined a lot of the story through the songs,” explains Wenders. “We agreed that there was not going to be any other music than what Hirayama is listening to because the film is very subjective. You do start to sneak into this man’s head more and more.”

When I saw the prices for these vintage cassettes, I started regretting that I threw a few thousand of them away in the Eighties

In some ways, Hirayama is a man out of time: He reads books rather than scrolling endlessly through the internet, and at one point his niece laughs in his face for thinking Spotify is a shop. Wenders can sympathise, and inserts himself into the film in a brief cameo, browsing the record shop where Hirayama goes on the hunt for a Patti Smith tape. “When I saw the prices for these vintage cassettes, I started regretting that I threw a few thousand of them away in the Eighties,” Wenders says with a laugh. “What an idiot! I could have financed my next trip to Japan.”

Wenders’s love affair with Japan dates back to his Eighties documentaries Tokyo-Ga, about the revered filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu, and Notebook on Cities and Clothes, which focuses on the fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto. Towards the end of making the latter in 1989, Wenders lost a pool game and a bet, which Yamamoto recently called in. This January, Wenders walked in the designer’s Fashion Week show in Paris (France), wearing a dandyish hunting jacket in one look and a black felt hat, suspenders and a pink hibiscus print shirt in another.

The director who once made a film called The Goalkeeper’s Fear of the Penalty was stunned when he noticed who was watching him. “I haven’t told anybody, but I have to tell you now,” he begins, leaning in conspiratorially. “The coolest moment was when I realised Zinedine Zidane was on the front row. That threw me. When I passed him, I did make my nod. I thought: ‘Wow! Who can say that you were doing a fashion show and that Zinedine Zidane was watching you?’ That was glorious.” He laughs contentedly. “Anyway,” he adds, “I’m never doing it again.”

Wenders was born in Düsseldorf in 1945 and began his career in the late Sixties as a pioneering figure in the New German Cinema era. Having grown up under the dark shadow of the Second World War, he turned his gaze west, to the landscapes he knew from the great American Westerns made by John Ford. Before making Paris, Texas, which follows Travis’ ill-fated attempts to reunite his family, he spent three months traversing the US to clear his mind of the impression those films had made on him. He wanted to be able to see the country for himself.

When it came time to shoot, Wenders recalls, he and cinematographer Robby Muller decided to do away with storyboards. “We said, we’re going to be in the landscape. We’re going to let the landscape and the light show us how to start the movie,” he tells me. “We were open to how the West wanted to be filmed, and that was a decisive moment in my life because it was really the first time [I’d shot without storyboards]. I never returned to my earlier approach afterwards, because it was so liberating to have the place and the light and the actor tell you how to shoot it.”

After Paris, Texas triumphed at Cannes, Wenders decided it was time to go home. He made his next film in West Berlin in 1987, two years before the wall came down. “Berlin was an island and you were locked,” he remembers. “Because you were locked in there, there was no crime. You couldn’t get away.” Wings of Desire is a staggeringly beautiful, existential poem of a film that also documents a remarkable underground music scene starring Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds and Crime & The City Solution, whose members included some of Cave’s former band The Birthday Party. “In Berlin, Nick was the undisputed king of the nightlife,” says Wenders. “He thankfully agreed to shoot that. If you watch the film now, it’s truly amazing how young he was. The whole thing is really amazing.”

Wings of Desire tells the story of a pair of immortal, invisible angels (Bruno Ganz and Otto Sander). When one falls in love with a trapeze artist (Solveig Dommartin), he longs to become mortal so he can be with her. Into this metaphysical Cold War romance, Wenders then drops Columbo. Peter Falk was best known for his role as the crumpled, smarter-than-he-let-on TV detective, but he also made movies with John Cassavetes that the pair of them improvised from open to close. Falk, who plays a version of himself, seemed to understand Wenders’s story intuitively. “Peter was a bomb,” says Wenders. “My two angels, of course, loved Columbo, but then they realised here was an actor whose whole acting approach was improvisation. My two angels were German, and brilliant stage actors, and they were [scared] s***less of scenes with him because they couldn’t hold water improvising along with Peter Falk.”

Great as they both are, Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire were of no interest to the Oscars. Before Perfect Days got the nod this year for Best International Film, Wenders had previously been nominated three times for documentaries: Buena Vista Social Club, 2011’s Pina about the dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch and 2014’s The Salt of the Earth, on photographer Sebastiao Salgado. The nomination of Perfect Days also marks the first time Japan has selected a film by a non-Japanese director to compete, which Wenders modestly put down to the immense popularity of Koji Yakusho. “He’s such an extraordinary man,” says Wenders, “I’m in on this Oscar race as his sidekick.”

Ever since algorithms tried to find out what I like, and only send me stuff that I ‘should’ like, I love my own library of music even better

There’s more to it than that. In Hirayama, Wenders has given us another character as profoundly impactful as Stanton wandering the desert in his red cap or Ganz pondering the pros and cons of mortality. If he at first glance seems out-of-touch, with his paperbacks and his cassettes, you might end up wondering whether he understands more about the modern world than any of us. With his unhurried disposition, he points the way towards a quiet stillness we’ve almost lost.

“In a strange way Hirayama incorporates something we’re all sort of longing for,” says Wenders. “I think we’d all like to regain control of our lives against being led by so many outside sources. Ever since algorithms tried to find out what I like, and only send me stuff that I should like, I love my own library of music even better. But what’s really essential to his character is the idea of reducing yourself, and that actually in reduction there is a strange remedy to our blues.”

‘Perfect Days’ is out now in the US and in UK cinemas from 23 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks