Call Me By Your Name to Battle of the Sexes: Why 2017 was a game-changing year for LGBT cinema

Since ‘Moonlight’ won an Oscar, a wider variety of queer films are getting the attention they deserve. The stars and directors of ‘Battle of the Sexes’, ‘Call Me By Your Name’, ‘Beach Rats’ and more talk LGBT representation, and how taboos are finally being broken on the big screen

While a few high-profile films have subverted the stereotyped or sidelined LGBT character in recent decades, such as Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (2005) or Todd Haynes’s Carol (2015), equality of LGBT representation in cinema still seems some way off. A US study on the top 100 films of 2016 showed that only 1.1 per cent of speaking characters were gay, lesbian or bisexual, no speaking character was identified as transgender, and only one film featured a gay protagonist. That film was Moonlight.

But Barry Jenkins’s film has perhaps turned out to be something of a game-changer. Scooping the coveted 2017 Best Picture Oscar, its success at Hollywood’s most prestigious award ceremony was seen as a coup, not only for featuring a gay protagonist (Brokeback was notoriously snubbed for the top prize back in 2006) but also for its rare depiction of homosexuality within the African-American community.

In its wake, this year’s film festival season has seen an incredible array of high-quality LGBT pictures with explicit representations of sexuality – not only on the arthouse margins of cinema but in the mainstream as well.

From Billie Jean King biopic Battle of the Sexes to Oscar-tipped Call Me By Your Name, God’s Own Country (Francis Lee’s ‘Yorkshire Brokeback’) to Sebastián Lelio’s A Fantastic Woman about a transgender singer, 2017 has seen a diverse range of narratives, from the overtly taboo-breaking to the understated slice-of-life, exploring themes such as complex desire and toxic masculinity in authentic, nuanced ways.

Michael Blyth, programmer at the BFI Flare, London’s LGBT Film Festival, notes it’s still too early to see how the critical and commercial success of Moonlight might change the landscape. But it is clearly a very exciting time for queer cinema, with the industry “slowly beginning to wake up to the need for diverse voices both in front of, and behind, the camera”.

The Independent spoke to some of the directors and actors involved in this year’s most prominent LGBT films about the characters and themes, and whether we really are seeing that long-awaited shift in the kinds of sexuality that can be depicted on the big screen.

Beach Rats

Out today is Sundance Award-winning Beach Rats. An incredibly raw and emotive film with a dark underbelly, it follows breakout British star Harris Dickinson as Frankie, a ruggedly beautiful, angst-ridden teenager caught between two worlds: playing ball and chasing girls with his layabout friends in gritty, outer Brooklyn, and closeted desires, given air through flirting with men online and meeting them by night on cruising beaches.

A fresh reinterpretation of the coming-of-age drama, writer and director Eliza Hittman explained to me how it built on her fascination with the genre, and her first female-centred feature It Felt Like Love. But with Beach Rats, her focus was “a young guy coming to consciousness about who he was”.

“And that,” she explains, “always involves sort of pain and a realisation. It’s not a beautiful transformative process, as people like to hope and imagine that growing up is.”

For her, depicting a young man’s struggle with his sexuality was not a goal in itself, but just a story to be told: “I think there’s room on the spectrum for a lot of different perspectives on sexuality. It’s just one representation of one experience in one part of the world.”

Dubbed by Hittman a “slice-of-life” film, there are no easy answers about Frankie. Instead, the audience finds themselves caught up and confused with their protagonist, particularly in his darker moments: “There are destructive consequences to living in a world where you have to hide who you are. It’s not an overtly message-driven after-school special obviously – but that is the feeling the film gives you.”

Battle of the Sexes

Also out today is Battle of the Sexes, the new film from directing duo Valerie Faris and Jonathan Dayton – the pair behind Little Miss Sunshine – loosely based on the historic 1973 tennis match between top women’s player Billie Jean King, and self-confessed “chauvinist pig” Bobby Riggs.

While ostensibly a sports biopic, Faris and Dayton’s interpretation looks at how the publicity stunt became a battleground for equal rights, and explores Billie Jean’s private life in the lead up to the match, including her struggle with her repressed sexuality.

Emma Stone gives the performance of a lifetime as Billie Jean King, fully inhabiting the role which, she told me at the film’s premiere, she prepared for “in any way I could – I was essentially living in Billie Jean’s body”.

Andrea Riseborough plays Billie Jean’s hairdresser-turned-lover Marilyn, and spoke passionately on the red carpet of exploring this intense love story: “She was a catalyst for Billie Jean really, in the sense she presented thinking of Billie Jean’s body in a sensual way, not as a machine. It was a sexual awakening.”

For Riseborough, who gets to tell these stories is also crucial. “It’s really important these stories are in the right hands. When I met Dayton and Faris, they were so compassionate. They understood what a wonderful film it could be and how it could resonate with so many different people.”

Call Me By Your Name

This stunning new film from auteur Luca Guadagnino was the talk of the film festival season. It centres on teenage Elio (Timothée Chalamet) whose passionate love affair with 24-year-old visiting academic Oliver (Armie Hammer) unfolds in a summer haze, in 1980s rural Italy.

Despite some controversy regarding the age gap between the characters – and a quickly-becoming-notorious intimate scene involving a peach – for Guadagnino, the film was not about breaking taboos. In fact, he tells me, many scenes ended up less explicit than in James Ivory’s script: “I don’t think it’s about taboo. It’s about people who ... look for the other and through finding the other they explore themselves.”

The director did reveal, however, at the film’s press conference that he faced challenges in financing the adaption of André Aciman’s non-conventional love story, as “it didn’t play according to the textbook of the coming-of-age film and, in particular, the gay coming-of-age film, where there has to an internal and external antagonist”.

The actors both spoke earnestly ahead of the film’s Mayor of London Gala screening about the challenges and commensurate rewards of bringing the necessary authenticity to their roles, with Hammer commenting: “I didn’t know that I could be that honest as a performer; it made me nervous being that vulnerable on film as an actor.”

Chalamet made comparisons between Aciman’s story and The Perks of Being a Wallflower, for providing a fantastic window into a young person’s experience “but with a sexual edge”, noting that such complex roles for young people are few and far between.

For Hammer, controversy comes with the territory when doing interesting work: “There will always be taboos to break and I think film is the same as all art, in that its job is to challenge everybody and challenge their perspective.”

Professor Marston and the Wonder Women

Before writing and directing Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, released last week, Angela Robinson had been obsessed with the true but little-known backstory to the controversial Wonder Woman comics. The creator, American psychologist William Marston (here played by Luke Evans), drew on his psychology theories and his polyamorous relationship with his wife Elizabeth Marston (Rebecca Hall) and his live-in mistress Olive Byrne (Bella Heathcote) for his fictional character.

Her film is a bold, sexy, and beautifully executed reinvention of the superhero origin story, which sits in stark contrast to the recent live-action movie featuring the comic’s heroine. In depicting the triangle of lovers, Robinson was determined not “other-ise” their experience: “We have these different words now, like polyamorous or BDSM. But they didn’t have words for what they were doing. They were just doing what they were doing.”

She also enjoyed shifting away from what she sees as the pervasive “male point of view” when it comes to desire in cinema, while “the exchange of power throughout the movie is kind of consent as foreplay”. In telling theirs like any other love story, she presents what she terms “radical normalcy”: by challenging assumptions of what normal is, the radical becomes normal.

Crucially, Robinson explains, the film holds a dialectic between fantasy and reality that ties into Wonder Woman. “Where they come together in a fantastical world of their own making, they’re able to be their truest selves – either by exploring their sexuality or role-playing. It’s like they’re liberated from the world.”

The Wound

Winning the Best First Feature award at the London Film Festival was The Wound, from South African director John Trengove, starring gay musician Nakhane Touré as Xolani, a factory worker who guides Kwanda, a city boy from Johannesburg, as he undergoes his rite of passage into manhood.

The intense, powerful film explores same-sex desire from three perspectives, as Kwanda asserts his queer identity while uncovering a hidden sexual relationship between Xolani and guide Vija.

In a joint interview with the director and lead actor, Trengove explained that he specifically wanted to set a story of same-sex desire within traditional culture, something he considered potent at a time when “horror stories were coming out of Uganda about the human rights abuses there”, and Robert Mugabe “was making all these statements about homosexuality being ‘un-African’”.

But he also wanted to avoid what he named the “The National Geographic” approach to a kind of ethnographic appreciation of the beautiful African landscape and the exotic black male body. In contrast, he takes us claustrophobically close to his protagonists, while some of the bigger sequences involving multiple non-professional actors from the Xhosa community are borderline-documentary.

Touré, with Trengove, wanted to explore the idea that there is a “prescribed an idea of masculinity” that “all men live in the shadow of”. While noting “the revolution can’t happen in the cinema – it has to happen outside”, Trengove said he was not aiming to present a thesis on “masculinity or sexuality or race or culture, but really to bring all of these ides into a kind of cocktail to let them coexist and see what comes up in the friction between them”.

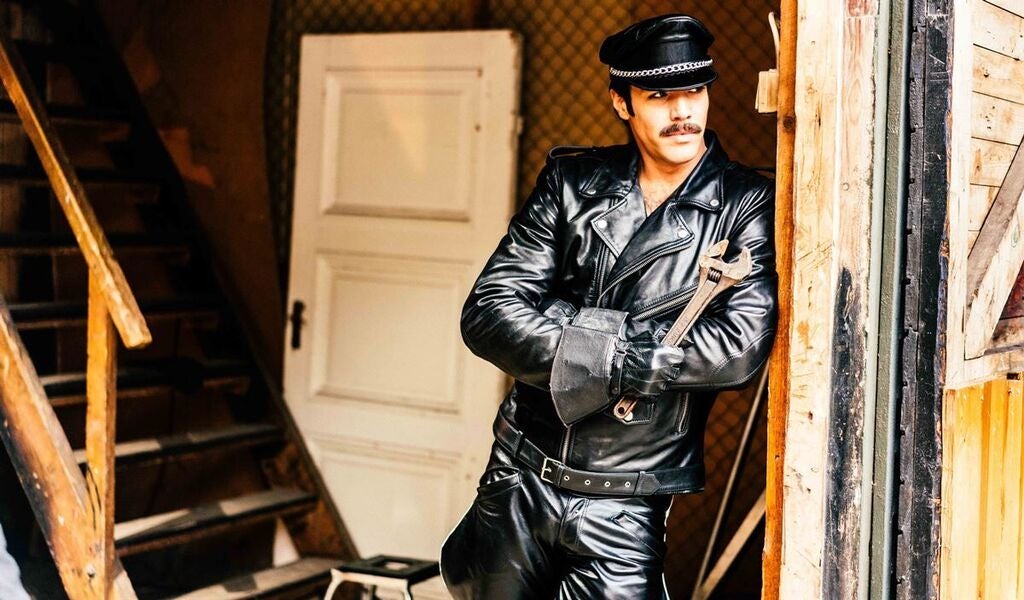

Tom of Finland

Finland’s entry into the 2018 Academy Awards, Tom of Finland, brings to the screen the story of the man behind one of the defining gay cultural icons of the twentieth century: Tom of Finland –, or rather, Finnish artist Touko Laaksonen. We see decorated WWII officer Touko, played magnificently by Pekka Strang, produce his illegal, homoerotic fetish illustrations, which eventually found mail-order popularity in 1960s US. With that came the status of a gay liberation icon, even as Touko also attempted to navigate his sexual desires in repressive post-war Helsinki.

Bulging and unashamedly explicit, his uniformed characters became a symbol of overt eroticism in the gay community, and helped give birth to an aesthetic visible from Queen to the Village People. But for some, the images remain as taboo today as they did then, as is evident from some conservative grumblings director Dome Karukoski told me he’s heard, “badmouthing the film as ‘gay-hugging’ and doubting its need to exist”. For Karukoski, it demonstrates that “taboos are broken an inch at a time”. He says: “I think we still left some to be broken.”

While the director jokes that award success and the stamp of approval from his mum are what he really seeks, an important goal has been achieved with film: “Tom’s story and life mission has been touching more and more people, and hopefully that will generate more understanding and a better society for sexual minorities to live.”

He sees cinema as one the most powerful mediums in its ability is to broaden audiences’ perspective: “One important way is to liberate laughter and emotions by creating emotional entertainment. When those emotions are opened, it causes empathy. And empathy is the key for a better world.”

‘Beach Rats’ and ‘Battle of the Sexes’ are in UK cinemas from 24 November. The Tom of Finland is available on a limited edition Dual Play disc now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks