What drives a director to remake their own film?

Michael Haneke is remaking Funny Games in English. He's just the latest director to revisit his work, as Leigh Singer discovers

Michael Haneke

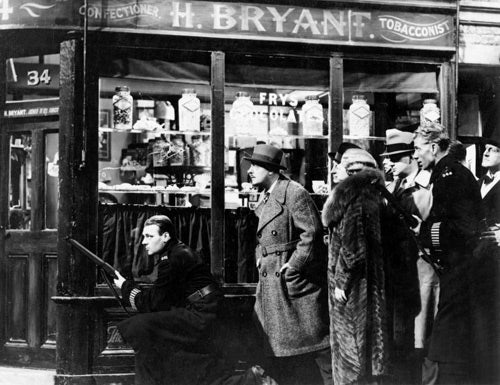

Funny Games (1997) / Funny Games US (2007)

Michael Haneke claims he always meant his merciless meta-thriller – an Austrian film with an English title – to reach American viewers and, 10 years on, he gets his wish. In this audience-baiting polemic on the nature of violence-as-entertainment, Haneke pits two well-to-do, polite sociopaths against a middle-class couple and their young son. The duo trap the family in their lavish house to torture them psychologically and, eventually, physically.

Haneke is doubtless hoping stars such as Naomi Watts and Tim Roth will entice people into his clinical mousetrap of a film – practically a shot-by-shot remake. The original was shocking a decade ago. Yet numerous you-like-to-watch-don't-you? thrillers released subsequently and the rise of the YouTube generation perhaps nullifies a message Haneke tackled more obliquely – and arguably more effectively – in his masterpiece, Hidden.

Cecil B DeMille

The Ten Commandments (1923) / The Ten Commandments (1956)

Cecil Blount DeMille's silent 1923 The Ten Commandments was billed as "the mightiest dramatic spectacle of all the ages"; his Fifties remake, "the greatest event in motion picture history". Both claims are now laughable, though the repeat suggests DeMille's penchant for excess and sermonising found its perfect match.

His original was epic enough. But the 1956 version, DeMille's biggest – and final – success is pure Old Testament and 70mm spectacle. Moses's (Charlton Heston) granite jaw seems hewn from the same slab as the commandments and the Oscar-winning visual effects – the burning bush, the famous parting of the Red Sea – though hokey today, inspired shock and awe. It's DeMille's tribute to the only showman he considered greater than himself: God.

Alfred Hitchcock

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) / The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)

How do you prefer your Hitchcock – black-and-white, gritty British, or exotic, glossy Hollywood? The plot in each of his espionage/kidnap thrillers remains roughly the same – an innocent couple stumbles over an assassination plot and their child is held hostage to ensure their silence – but offers a fascinating comparison of his early and later career.

Both versions have their pleasures. In the first, Edna Best's heroine is a resourceful Olympic-standard markswoman and Peter Lorre an effective bad guy. Doris Day is far more passive in the remake and the villains less memorable. Then again, it does have James Stewart and more intricately sustained suspense sequences, notably the Albert Hall climax. Hitchcock's made clear his own preference, claiming, "the first version was the work of a talented amateur and the second was made by a professional".

Francis Veber

Les Fugitifs (1986) / Three Fugitives (1989)

Hollywood has reimagined French film-makers from Renoir (Boudu Saved from Drowning was remade as Down and Out in Beverly Hills) to Godard (A Bout de Souffle became Breathless) but the roi of remakes is comedy writer-director Francis Veber. So far, seven of his scripts or films have been Americanised, usually with less-than-impressive results.

In the late-1980s, Veber went Stateside to helm the remake of his Les Fugitifs, with Nick Nolte and Martin Short in the Gérard Depardieu/Pierre Richard roles of career criminal trying to go straight and hapless first-time robber with a sickly young daughter. It's not all bad, but the sentimental-slapstick combination translates as frantic schmaltz.

George Sluizer

Spoorloos (1988) / The Vanishing (1992)

Whenever it co-opts foreign-language films, Hollywood is typically cast as the great corruptor of pure world cinema. Not an excuse that film-maker George Sluizer can use, however, as he reworked his peerless Dutch thriller Spoorloos, about a man's obsessive quest for his missing girlfriend and the cat-and-mouse game played with her abductor, into one of the worst remakes of all time.

In place of the original's mounting sense of dread and implacable, inexplicable evil, Sluizer offers us Kiefer Sutherland's macho histrionics and a lame back-story to "explain" Jeff Bridges's villain. Most unforgivable of all, Spoorloos's terrifying, uncompromising ending was junked for an offensively pat nick-of-time rescue. The chilling original lives on while the remake has been deservedly buried without a trace.

Michael Mann

LA Takedown (1989) / Heat (1995)

After Miami Vice, Michael Mann was looking to establish a new police television series. 1989's LA Takedown was the pilot episode, though when the project was aborted, Mann's loss was a future jackpot. Expanded into a three-hour crime epic, Heat is the film that confirmed him as one of modern cinema's heavyweights.

Mann made the most of the extra opportunity to flesh out relationships and dynamics, exercise his fearsome technical prowess and hire the best actors. Watching the first film second, it's fascinating to witness scene after familiar scene – the post-heist street shootout, the coffee shop head-to-head – unfold, with unheralded, often over-emphatic actors. It's a little like watching a village hall drama troupe tackle Shakespeare: earnest, passionate but simply lacking, though better actors than Alex McArthur and the late, unfortunately named Scott Plank would be hard-pressed to match Robert De Niro and Al Pacino.

Robert Rodriguez

El Mariachi (1992) / Desperado (1995)

In 1992, guerilla film-makers thrilled to the story of El Mariachi, a DIY shoot-'em-up about a Mexican gun-slinging guitar hero, made for $7,000, largely funded by writer-director-cameraman-editor Robert Rodriguez subjecting himself to medical experimentation, that became a cult international hit.

Gatecrashing Hollywood and adding three zeros to his budget, Rodriguez followed it up with Desperado, a retooling of his debut, now armed with cash, a crew and Latino stars Antonio Banderas and Salma Hayek.

Slicker and busier, Desperado upped the stakes and cemented Rodriguez's status as mainstream auteur. Banderas and Hayek radiate fiery heat, but in terms of raw charm, invention and on a bang-per-buck ratio, El Mariachi remains the last man standing.

Ole Bornedal

Nightwatch (1994) / Nightwatch (1997)

A university student (Ewan McGregor) takes a job at a morgue only to find himself implicated in a series of gruesome prostitute murders. Dimension Films quickly snapped up Ole Bornedal's Danish smash-hit, then drafted Bornedal in – with Steven Soderbergh co-scripting – to direct a supposedly refined American remake.

Though the promising B-movie set-up and several shot-for-shot stalking scenes remain, the retread rips off David Fincher's Se7en something rotten (despite Bornedal's 1994 original pre-dating it), with its fetid interiors and disgust with humanity. It also loses the original's winningly scabrous tone. A grunge-chic remake that's all sheen and no soul.

Takashi Shimizu

Ju-On (2003) / The Grudge (2004)

Since the young Japanese director Takashi Shimizu first released a video entitled Ju-On (The Grudge) in 2000, about a virus-like curse that haunts and kills its victims, he's been responsible for six Grudge movies: a pair of Japanese video premieres, two Japanese features and US remakes of both. Fans might call him a perfectionist; critics, a one-trick pony.

Truth is, the Grudge formula is so straightforward that identikit English-language remakes were inevitable (even if, admirably, still set in Japan).

'Funny Games US' opens on 4 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks