Marni Nixon: How Audrey Hepburn’s ghost singer was sworn to secrecy by Hollywood

As the voice of Maria in ‘West Side Story’ and Eliza Doolittle in ‘My Fair Lady’, Marni Nixon should have been one of Hollywood’s biggest stars. Instead, other actors got the credit and she became American cinema’s ‘most unsung singer’, writes Alexandra Pollard

Oh Natalie, it’s just wonderful – absolutely wonderful.” That’s what Hollywood producers told Natalie Wood as she belted out her songs as Maria in 1961’s West Side Story. Then they turned to Marni Nixon – the woman who, unbeknown to the film’s star, would be re-recording all of Maria’s songs – and winked.

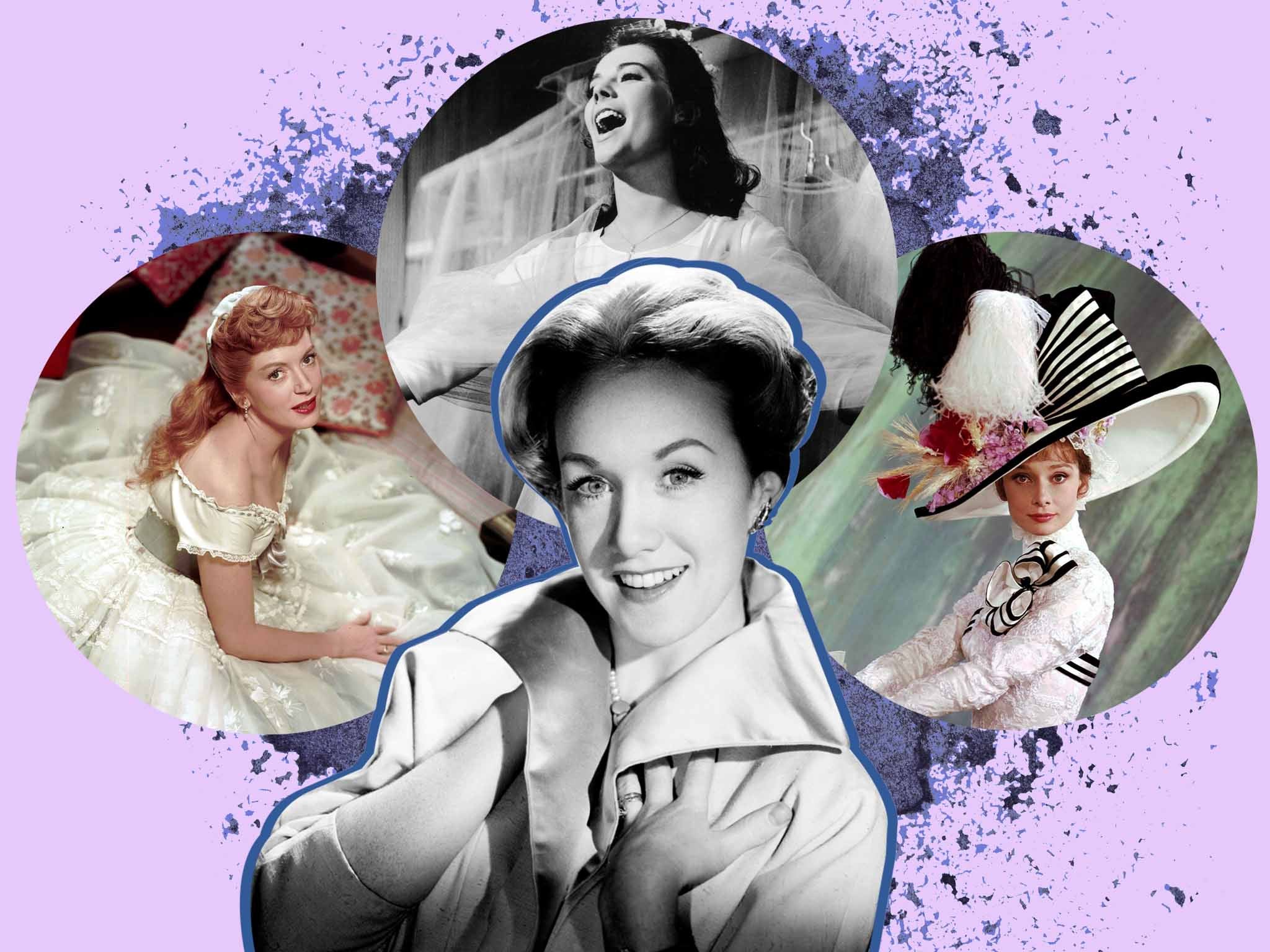

You probably don’t know Marni Nixon’s face, but you will know her voice – a trilly, gleaming soprano that adapted to suit whoever’s mouth it was supposed to be emerging from: Natalie Wood; Audrey Hepburn; Deborah Kerr; Marilyn Monroe. Referred to as “American cinema’s most unsung singer” by The New York Times, Nixon not only did all of Wood’s singing for West Side Story, but Hepburn’s for My Fair Lady, Kerr’s for The King and I, and Monroe’s – though only for one particularly tricky line – in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. “Somewhere”? “I Feel Pretty”? “I Could Have Danced All Night”? “Getting to Know You”? All Nixon.

She didn’t set out to be the voice of anyone but herself. After playing “freckle-faced brats” in a string of Hollywood films as a child, she became a private pupil of famous soprano Vera Schwarz and embarked on a career as an opera singer. Her career as a ghost singer came about by chance. After lending her dulcet tones to the angels heard by Ingrid Bergman in 1948’s Joan of Arc, she was asked to dub some singing for Hollywood star Margaret O’Brien in 1948’s Big City. She filled in again for O’Brien the following year, this time for a tricky Hindu lullaby in The Secret Garden.

Nixon quickly discovered that she could mirror actors’ emotions – and echo the timbre of their speaking voice in her singing – so seamlessly that the audience wouldn’t notice the switch. And it was vital that they didn’t: Nixon was sworn to secrecy by Twentieth Century Fox. “They said, ‘If anybody ever knows that you did any part of the dubbing for Deborah Kerr, we’ll see to it that you don’t work in this town again,’” she once recalled. Despite the soundtrack selling hundreds of thousands of copies, she earned just $420 for singing every single note of Deborah Kerr’s songs.

So why not just cast Nixon in the roles? Nowadays, directors either hire actors with enough on-screen gravitas to make up for their unpolished singing (think Helena Bonham Carter in Sweeney Todd, or Nicole Kidman in Moulin Rouge!), or cast up-and-comers who can sing impeccably (as Steven Spielberg did with Rachel Zegler for his new version of West Side Story). But back then, “Hollywood wanted recognisable stars”, Nixon once explained. “And the fact that a lot of the stars couldn’t sing was only a minor inconvenience to the big producers.”

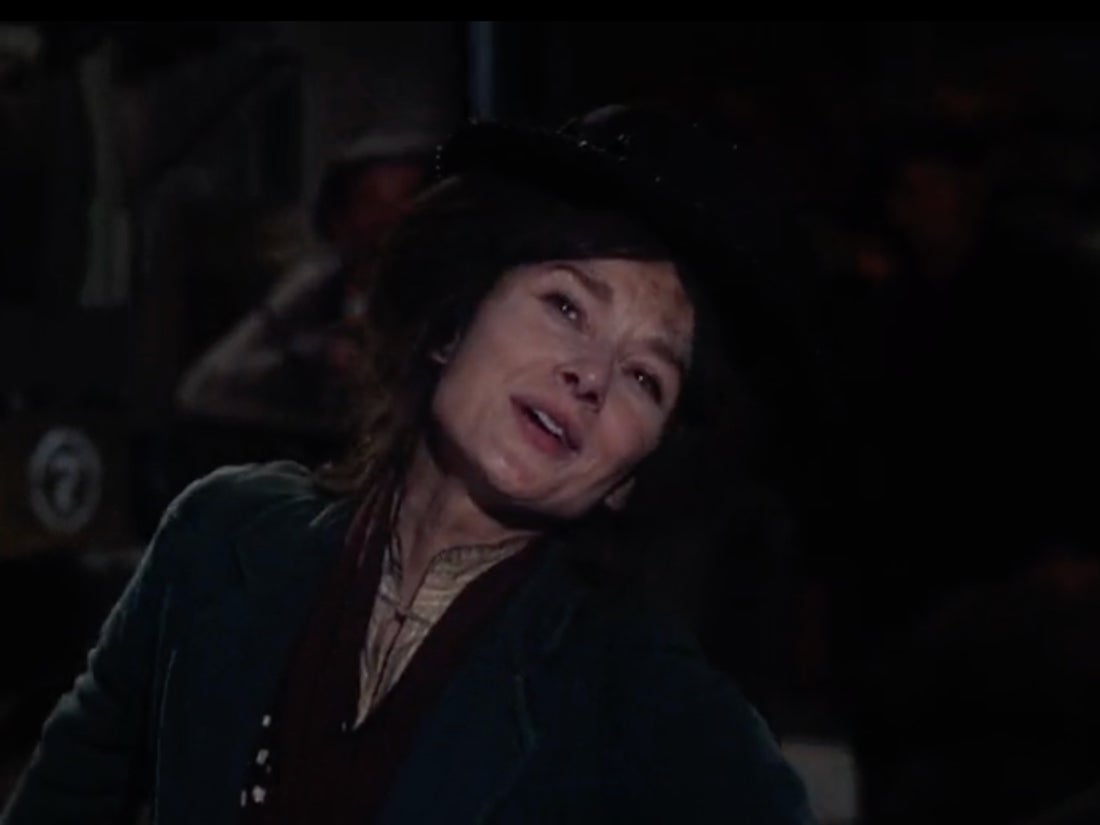

Some of those stars were only too happy to let Nixon make them sound good. Others were insulted by the very thought of it. Wood was positively fuming. The studio kept the Oscar-nominated actor in the dark throughout the filming of West Side Story, terrified that she would pull out if she knew the truth. They let her record all of her songs, orchestra and all, knowing full well that they were going to “throw it all out” and use Nixon’s voice instead. When Wood was filming her scenes as the lovestruck Maria, they had her mime along to her own recordings, not Nixon’s, to keep up the ruse.

“It created an atmosphere of… I felt very uneasy,” Nixon told NPR’s Terry Gross in 2003. Required to shadow Wood on set and in the studio to help with her performance, she felt uncomfortable being forced to lie to her. When the producers would mock Wood behind her back, “I just felt like I wanted to cringe”. Once the film was safely in the can, Wood was told the truth. “From what I’ve heard, she was just absolutely furious,” said Nixon, “and stomped out of the studio in a total rage.”

Still, a hefty salary, glowing reviews and a near-clean sweep at the Academy Awards softened the blow. Nixon, meanwhile, was paid next to nothing, her name omitted from the credits, her role kept a closely guarded secret. She was so poorly remunerated that the musical’s composer Leonard Bernstein gave her a percentage of his own cut from the soundtrack, knowing that without her singing, the film would not have been what it was.

A few clips exist online of Wood’s original singing. Though Maria’s numbers are hard to sing, the results aren’t exactly terrible: a little pitchy here, a little lacking in power there. But they’re not a patch on her acting – or on Nixon’s singing.

Audrey Hepburn was more welcoming. She would drive Nixon to set every day in her limousine, and try and help her pronounce certain words – a Cockney accent is not easy for an American, as Dick Van Dyke can confirm – but she, too, wanted desperately to do her own singing. She had been told that if she kept training and improving, Nixon’s voice would only take over for the high notes – though by some accounts that was an empty promise.

Having been controversially chosen for the role of socialite-in-training Eliza Doolittle over Julie Andrews – who had originated it on stage and had a wonderful voice – Hepburn felt the pressure. She thought that “if she had taken Julie’s place and then couldn’t sing, it would reflect very badly on her”, recalled score composer André Previn in Barry Paris’s Aubrey Hepburn biography.

Hepburn took intensive voice lessons, and would sneak into the sound stage after Nixon finished dubbing to try and record a good enough take that they would agree to use her voice. “They gave me tapes of her singing,” Nixon told People magazine in 2015, “and I could hear her saying [to herself], ‘Oh darn, I think I can do better. Maybe I can’t.’ She was really hard on herself. But she kept trying.”

Eventually, it was broken to Hepburn that despite all the training, rehearsing, recording and retakes, almost none of her singing would be used. “Oh!” she said, and walked off the set. The next day she returned, and apologised for her “wicked” behaviour. “That was her idea of being very wicked,” recalled Nixon. “She grudgingly agreed that she was not quite doing it the way they wanted her to sing it. She was very helpful.” By the end, their relationship became one of collaboration rather than competition. “I really felt fused with her.”

Nixon never saw herself as a disembodied voice; she didn’t want to simply churn out the right notes, but to convey what the actor was thinking and feeling. “It’s fascinating, getting inside the actresses you’re singing for,” she told the New York Journal-American in 1964. “It’s like cutting off the top of their heads and seeing what’s underneath. You have to know how they feel, as well as how they talk, in order to sing as they would sing – if they could sing.”

Still, by the time My Fair Lady came out, Nixon was done with dubbing. For one thing, she had grown tired of getting no credit. For another, she was suffering from an identity crisis of sorts: “I learned to adapt my own voice to suit the facial and mouth movements and even the enunciation patterns of the actresses I sang for,” she said. “It got so I’d lent my voice to so many others that I felt it no longer belonged to me. It was eerie. I had lost part of myself.”

By 1981, it was less a closely guarded secret than an open one that Nixon had done the singing for Hepburn and Wood. When Nixon embarked on a nightclub residency that year, The New York Times ran the headline: “Singing ‘Ghost’ Starts Out on Her Own”. The show was a tribute to Lerner and Loewe, the lyricist and composer behind a string of successful musicals – including My Fair Lady. It meant that Nixon could sing “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” and “I Could Have Danced All Night” – “and this time”, she told the press, “nobody is going to be fooled into thinking that’s Audrey Hepburn singing”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks