What Werner Herzog’s new film ‘Lo and Behold’ reveals about the internet

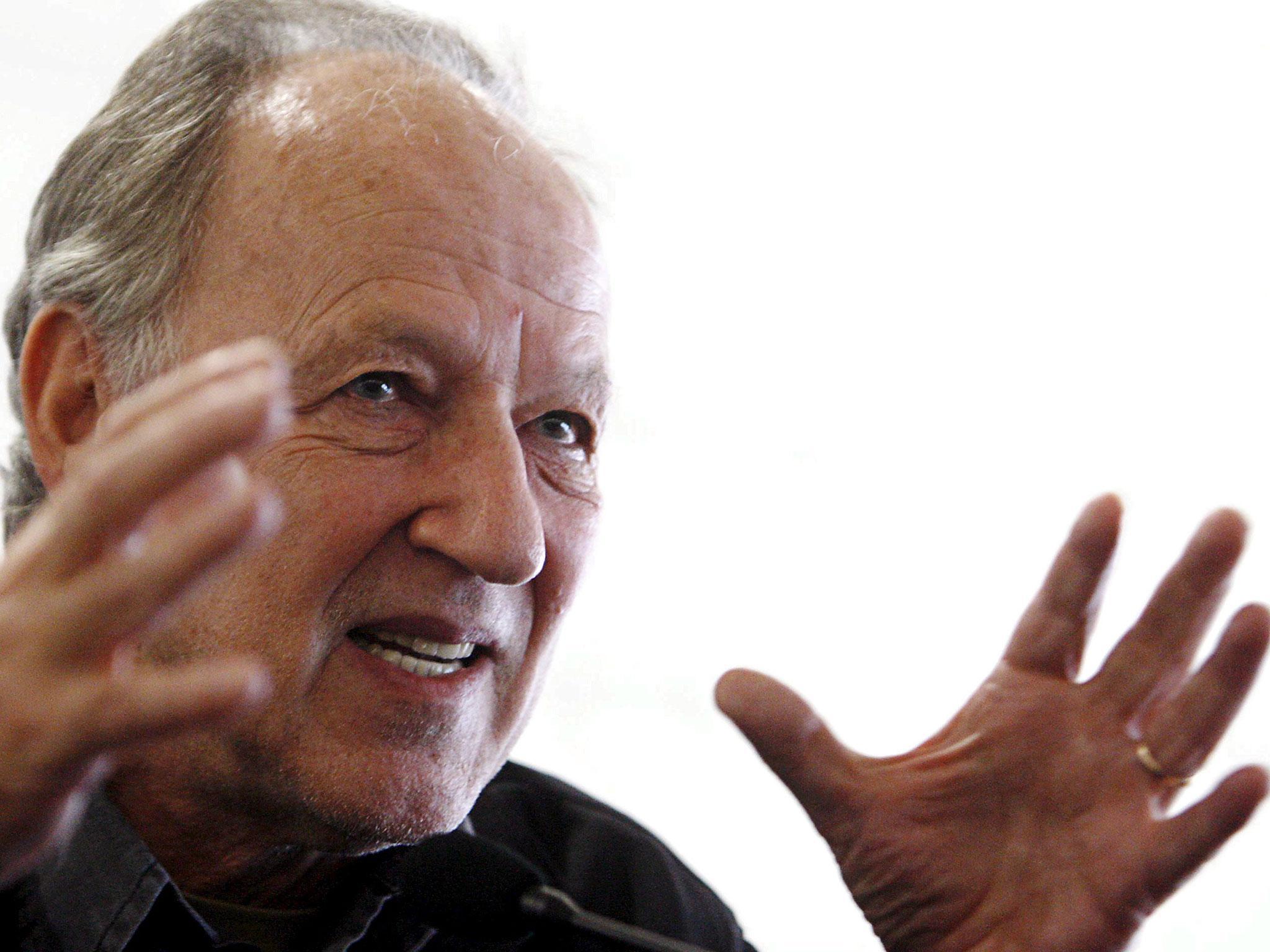

As the internet makes its way into more aspects of our everyday lives, Werner Herzog takes a closer look at the ethics of information flows in a new documentary. Alexander Nazaryan meets the German filmmaker

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Do not look at the photos of the Nikki Catsouras car crash that remain on the internet, lingering there maliciously despite the efforts of her parents to scrub them through ReputationDefender and, more simply, pleas to human decency. Look at pictures of Rollerblading dachshunds, click through a BuzzFeed quiz about Full House, read an article about Donald Trump’s grooming habits. Take a walk, for God’s sake. The photos of Catsouras’s mangled body hanging out of a car, head split open – as well as the story of how those photos ended up being disseminated on the internet – represent the most debased instincts of humanity. I gave in and looked, thinking they couldn’t be that bad. I was wrong.

The remaining members of the Catsouras family are featured in Lo and Behold, the new documentary by Werner Herzog about the founding of the internet, our struggles to understand its effects on us today and the even greater influence it may have on our tomorrows. Its subtitle is “Reveries of the Connected World”, but the film’s section that focuses on Catsouras’s death feels less like a reverie than an anger-tinged lament, not only for the girl but for a world not yet populated by anonymous trolls whose digital jabs can cause real wounds.

On October 31, 2006, Catsouras, 18, took her father’s Porsche and drove it down California State Route 241 at 100 miles per hour. As she tried to pass a slower vehicle, she lost control and smashed into a toll booth. First responders were greeted with a gruesome scene, which they photographed, sending the photos to two dispatchers. The dispatchers thought to share the bloody tableau with outsiders. They at first forwarded the photos through email, but secrets do as well on the internet as in a sixth-grade classroom, and soon enough the images of Catsouras found their way to sites that promulgate images of death.

Someone made a fake Myspace page for the girl, according to Newsweek’s Jessica Bennett, who helped make this story a national outrage. Trolls gonna troll, but why they decided to troll a grieving family is impossible to understand. But they did, descending on the Catsourases with a mirthful vehemence, sending them photos of Nikki, often with messages attached. “Woohoo Daddy! Hey daddy, I’m still alive,” one said.

Herzog did not look at the photos of Catsouras – and this is a man who once listened to audio of a man being devoured by a bear. “The transgressions make you speechless,” he says when I met him in Los Angeles on a recent afternoon. Nor does Lo and Behold describe in any significant detail the vitriol directed at the Catsouras family. “Unspeakably evil,” he says about that.

Herzog does not have a smartphone and is not an avid internet user, but Lo and Behold persuasively makes the case that digital technologies will become only more advanced and ingrained in the human experience. “You better learn how to cope with it,” he warns me with a schoolmaster’s sternness.

Believe me, Werner, I am trying. But between ruin porn, death porn and just plain old porn; 17,000-word exposés of the organic food industry; Periscope videos from Syrian refugee camps; and Christopher Walken Gifs, the coping can start to feel like drowning, until there I am, looking at the photos of Nikki Catsouras again.

There was a time, not all that long ago, when Herzog was regarded as one of the great auteurs of the New German Cinema, the uncompromising director who threatened to shoot (not with a camera) his star, Klaus Kinski, on the set of Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and had a steamship dragged through the Amazon for Fitzcarraldo (1982).

Today, though, Herzog is best known as a documentarian, especially to younger viewers. In the past decade or so, he has repeatedly trained his camera on wonders both human and natural: a man who moves to Alaska to consort with bears (Timothy Treadwell, the tragic hero of Grizzly Man, 2005); the strange creatures, some of them human, that thrive in Antarctica (Encounters at the End of the World, 2007); and the prehistoric imagery in the Chauvet cave in France (2010’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams). The disparate subjects are united by Herzog’s curiosity, his openness to the weird and wonderful – but also to that which terrifies and confounds. There is a patience to Herzog’s documentary work, and a reluctance to judge. And what some take to be a lack of humour on the native Bavarian’s part (he has long lived in LA) is really an admirable refusal to descend to sarcasm.

In 2013, Herzog made From One Second to the Next, a 35-minute documentary about texting while driving, at the behest of AT&T and other telecommunications companies. It was a bracing look at an activity both lethal and common, one that has led Herzog into the Fitzcarraldian jungle that is the internet. “I see there’s something going in civilization,” he told the Associated Press at the time, “which is coming with great vehemence at us.”

Like its predecessor, Lo and Behold is a collaboration between Herzog and a corporate patron: this time, NetScout, a Massachusetts-based cybersecurity company. Each of the documentary’s 10 chapters explores some facet of our digital lives: the rise of robots, the fear of electromagnetic waves, the internet’s founding legends. He talks to the Catsouras family, whose matriarch calls the internet “the manifestation of the antichrist,” and to Leonard Kleinrock, a computer scientist from the University of California at Los Angeles whose work on ARPANET in the 1960s allows us, today, to finish an Excel report while streaming the Hamilton cast recording. Standing in the plain room where the very first message over a rudimentary version of the internet was sent (an aborted missive from which the film takes its name), Kleinrock marvels at the “delicious old odor” of the ancient machine, which for him – and for millions of others – might as well be the Shroud of Turin.

Lo and Behold is a survey of the beast Kleinrock and his peers have created. They couldn’t have foreseen, of course, that the enormous machines that sent messages between research centres would morph into a digital overlay on the human experience, one where state secrets compete with hockey bloopers. As the Silicon Valley pioneer Danny Hillis tells Herzog – in what sounds nearly like an apology – in the 1970s you could find the identity of an internet user through the ARPANET Directory, a sort of White Pages for every person who was online. Today, about 3.2 billion people use the internet around the world. As Herzog says, CDs containing a single day’s worth of global data flow would reach “to Mars and back.” Even so, we are probably living in “the digital Dark Age,” Hillis says.

Although Lo and Behold is narrated by Werner – the Teutonic dryness in his voice lightly masking the curiosity beneath – he mostly stays out of the way, letting his subjects do the talking. The legendary hacker Kevin Mitnick recalls his pursuit by the government, the ludicrous allegation that he could launch nuclear missiles simply by whistling into a jailhouse phone, and the year he spent in solitary confinement. Elon Musk, the Tesla founder, confidently muses about the colonisation of Mars. But in a remarkably unguarded moment, he tells Herzog that he never remembers his dreams, only the nightmares. Rarely has one of Silicon Valley’s sunny, delight-bearing titans admitted to a darkness within.

“Yes, it has its dark, evil sides, and it has its glories,” the meticulously agnostic Herzog says to me as I try to tease out condemnation or praise. He may well be the last person on Earth without a strong opinion about the internet. Lo and Behold refuses to hammer the reader with argumentation: this is an anthology, not a hot take, its questions not gotcha but tell me. As the Carnegie Mellon computer scientist Joydeep Biswas praises a soccer-playing robot, Herzog asks him if he loves a puck-shaped gizmo named Robot 8, apparently the team’s star.

“Yes, we do,” Biswas says without any hesitation, or shame. “We do love Robot 8.”

In her thoughtful new book about digital culture, Magic and Loss, Virginia Heffernan argues that the internet is “the latest and most powerful extension and expression of the project of being human.” This is remarkably similar to Herzog’s view of all that Silicon Valley has wrought as “a phenomenal achievement of human dignity,” as he put it to me, one that is as awesome and dangerous as fire; that same achievement is “mysterious and maddening,” in Heffernan’s words. In many ways, Magic and Loss serves as an excellent companion piece to Lo and Behold, because both are signs of a conversation evolving beyond save-the-world utopianism and The Matrix-is-coming dystopianism.

I press the point with Herzog: if the internet is a tool, is it a tool like penicillin or a tool like the atom bomb?

“Not easy to accept the question as it is,” he counters with a touch of exasperation.

Some will wonder how a man so obviously enthralled by the internet can use it so little. He rarely goes online other than for emails and navigation – and in the latter case, he still prefers a paper map, the kind that won’t tolerate many pins. “My social network is my dinner table,” he says. Any guest placing an iPhone next to her wine glass should not expect another invitation to eat steak at the Herzog household.

While he is happy to lead a largely analog existence, Herzog knows he is the subject of many internet memes, as well as parody accounts like @WernerTwertzog, which dispenses seemingly Herzogian morsels of faux-dour wisdom: “Life is a parade of absurdities and pain, and then we die, alone, in filth. So, yes, little girl, I shall buy a box of Thin Mints.” The real Herzog, the one sitting across from me, says he welcomes these parodies, calling his various online chimeras “my unpaid bodyguards,” protecting his true identity with their fake ones. And when I suggest, jokingly, that I will live-tweet our conversation in an act of meta-journalism, he seems enthusiastic about the prospect. “It would actually be interesting,” he says. Later, he allows me to take a selfie – “If you need to” – though he warns he will not smile.

And when I bemoan the proliferation of cat videos, he rises to the defence of the internet, which is the triumph of the useless, and the beautiful, the cruel and the ingenious and the insane, the place we go when we are bored, when we are lonely, when we want to know Steph Curry’s stat line and why your knee is making a weird sound and why they tore down the Bastille and what happens when we die, which we will, unlike the internet, which will not.

“There are fantastic, crazy cat videos out there,” says Herzog. “Nothing wrong about it.”

© Newsweek

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments