The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Like what you see? Why voyeur films like ‘The Woman in the Window’ continue to captivate us

Netflix’s latest blockbuster carries on an age-old tradition in cinema. Annabel Nugent taps into the enduring legacy of voyeur films and explores what it means to watch the watcher

There is a young couple who live in the flat across from mine. My kitchen window looks directly into their living room. In the past year, I’ve become accustomed to the rhythms of their shared life. When I am making coffee at 7am, they’re not awake yet. When I go to sleep, they’re watching something on a laptop (they have a TV but maybe it’s broken because they never use it). If cinema is anything to go by, I’m one step away from witnessing a murder.

Lockdown has made spies of us all. Whether that’s as casual observers or tattletales, quarantine gave us either the time, the boredom or the government green light to indulge our nosiest impulses. And without social media updates from our loved/loathed ones, it was back to basics: straight on-tap, in-real-life curtain twitching. It’s why Netflix’s latest offering, the highly anticipated and much-delayed The Woman in the Window is being called “timely”.

The thriller, which debuted on the streaming service on Friday, is an adaptation of the bestselling novel by the pseudonymous AJ Finn (aka Dan Mallory, an author whose real life contains even stranger twists than his fiction – the former editor was the subject of a New Yorker exposé in 2019 in which he is accused of lying about having brain cancer and urinating in cups that he would leave around his boss’s office).

The Woman in the Window stars an off-kilter Amy Adams as Anna Fox, a child psychologist who is recently and debilitatingly agoraphobic. Confined by the walls of her five-storey brownstone in Manhattan, she drains bottles of red wine and prescription meds. Anna’s self-imposed asylum turns into an observation deck when she uses a high-tech camera to spy on her new neighbours in apartment 101. Although most of us have been coping fine with the iPhone lens, similarities between Anna and our lockdown-era selves are ripe for comparison. At least until she witnesses the brutal murder of her friend Jane (Julianne Moore) at the hands of Jane’s husband (an uncharacteristically hammy Gary Oldman). Or at least that’s what she thinks she’s witnessed – all those pills can really do a number on your mind, a detective later chastises her.

But while the film might appear to have arrived at an opportune moment, The Woman in the Window picks up on a longstanding tradition of voyeur films. Cinema has always been aware of our voyeuristic tendencies. In fact, the industry banks on it. Are we not all voyeurs when we go to the theatre, observing the lives of strangers? Never mind that they’re fictional.

Every voyeur film since 1954 has been immediately compared to Hitchcock’s classic Rear Window – an adaptation of Cornell Woolrich’s 1942 short story. James Stewart plays Jeff Jefferies, a photographer who is suddenly housebound after an accident leaves him laid up in a wheelchair with only his unknowing neighbours for entertainment. Every window in the building across the courtyard from his home presents Jeff with self-contained miniature theatres. There is a romantic dramedy unfurling at Miss Lonelyhearts’s apartment. There’s a kitchen sink drama a couple of windows across, where a composer laments his failing career. Most compelling though, is the thriller playing over at the Thorwald flat, where to Jeff’s horror (or delight), he is convinced a husband has killed his wife.

The director’s camera movements mimic his protagonist’s perspective, entangling the audience in Jeff’s voyeur activities – which still feel a bit ethically icky, even if they do end up solving a murder. His ogling of the young, blonde ballerina he nicknames Miss Torso, hits an especially unsavoury note.

Through what Jeff sees, and some of the morally dubious choices he makes, Rear Window unpicks the seams of America’s mid-century picket-fence domesticity. It’s a message that’s picked up some 30 years later by another of cinema’s most notable voyeur films, Blue Velvet. David Lynch’s 1986 provocative neo-noir thriller begins with a Peeping Tom moment that sends a strait-laced college kid (Kyle MacLachlan) into a sadistic underbelly that shudders itself to the surface of his picture-perfect town.

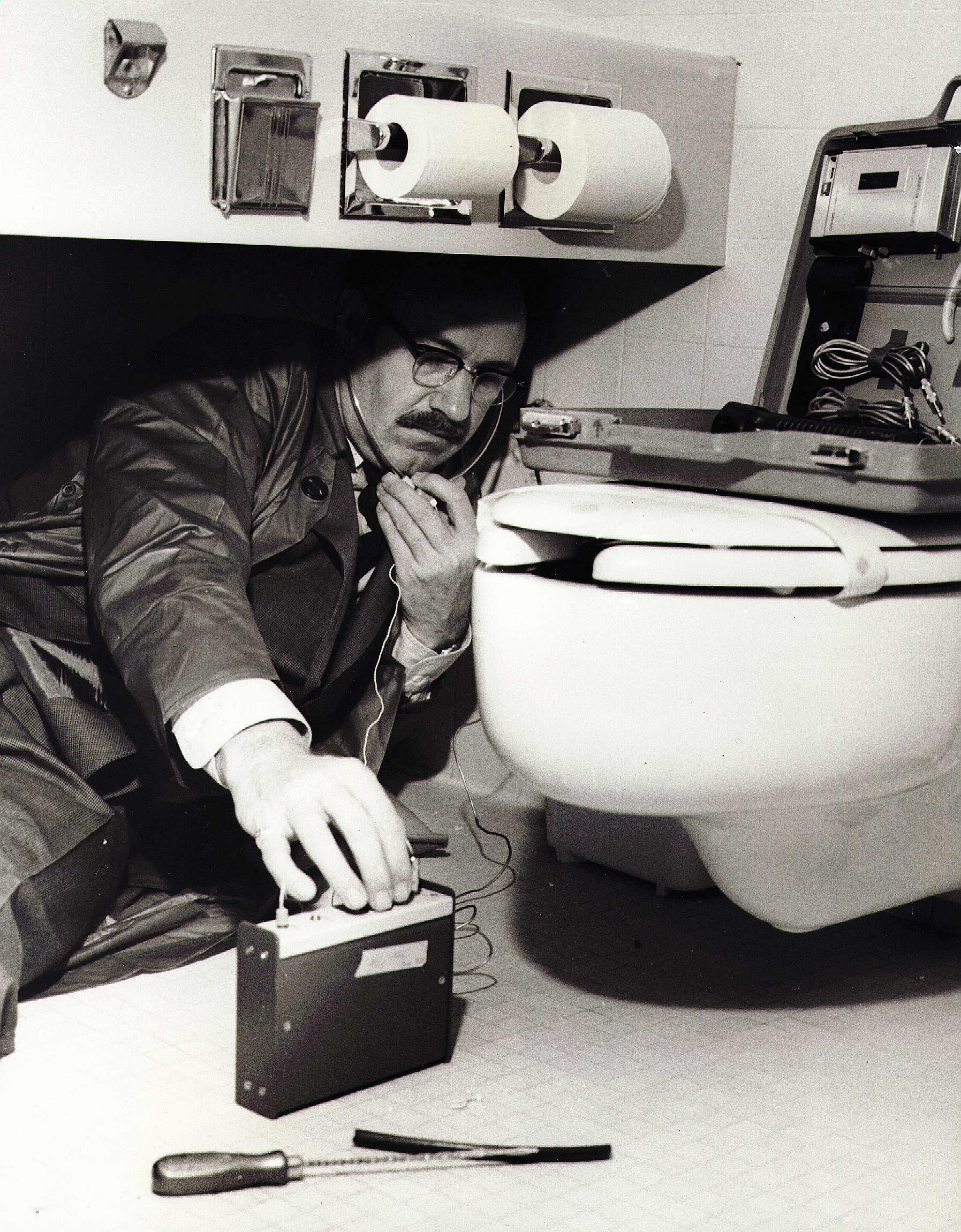

While questions of passivity and complicity are only signalled at briefly in Rear Window, they are the crux of The Conversation. The 1974 small-scale thriller by Francis Ford Coppola (who incidentally also wrote and directed a softcore “nudie” film about a hapless voyeur called The Peeper in 1960) places its audience at the junction where voyeurism meets paranoia. Gene Hackman is the miserable Harry Caul, a surveillance specialist hired to listen in on private interactions. He faces a crisis of conscience when he suspects that the adulterous couple he has been paid to listen in on are in danger of being murdered.

The film brings into doubt the passive position we assume as voyeurs. We learn that Harry’s snooping once led to the deaths of a woman and her child. In an early scene, he tells a priest in confession: “I was in no way responsible. I’m not responsible. For these and all my sins of my past life, I am heartily sorry.” But why apologise if you are not responsible?

The film isn’t about Watergate (a first draft was completed in 1970, two years before the Nixon scandal erupted into public consciousness), but it did tap into the Seventies anxiety around privacy. Harry’s festering guilt and growing sense of responsibility quickly manifests into a paranoia that he – a professional watcher – is suddenly the one being watched. Throughout the film, he is distraught to discover how fragile his privacy is. His landlord gains easy access to Harry’s triple-locked apartment to leave him a birthday present. Despite Harry not listing his phone number, both the landlord and a client are able to reach him. His mail is opened and read. Defence, Coppola shows, is futile and privacy is a myth. “We’ll be listening to you,” is the last thing the audience hears before seeing Harry rip up his apartment trying to find a bug that may not even be there.

Nowadays many of us take constant surveillance as a given. We paste tiny stickers over our laptop cameras and have accepted the fact that Siri is a listening bug, regurgitating social media ads for the dog food we talked about that one time, two days ago. Still, even in modern times the voyeur film has thrived – an apt vehicle for implicating its audience in the action and peeling back layers on a supposed reality. Take Caché. The 2005 critically beloved thriller by Michael Haneke is a modern-day voyeur triumph. The film begins with a lengthy stationary shot of a nondescript townhouse in Paris. Movie titles appear in small white text. So far, so ordinary. A woman leaves the building, but the camera stays trained on the house as she exits the frame. More time passes and then more after that, until a man and woman speak. “Where was it?” he asks in French. We discover that what we are watching is the same thing that the couple are watching: a videotape that they have been sent of their own house. Someone has given them a tape to let them know they are being watched and now, we (the audience and the couple) are all watching them being watched.

Variations on the opening scene crop up again and again. Learning to tell the difference between what is a tape and what is “real” becomes a test of subjectivity that materialises as a feeling of perpetual surveillance. Even the “real” scenes are drawn out to suggest that somebody may still be watching. Taking a page out of the Hitchockian bible, Caché makes a character of the camera itself. Rather than presenting information to us, its movements become cryptic and ultimately deceiving.

In the context of these cinematic triumphs then, it is disappointing to see The Woman in the Window drop the voyeur ball so clumsily, despite its eagerness to establish itself as part of the genre. There’s Rear Window playing on the TV in the opening shot, and grainy security footage of oblivious strangers peppered throughout. Then there’s the eye motifs crammed into every second scene. But the film doesn’t do much else with the trope beyond saying: “Hey, look at me! I’m also a voyeur flick.” The story that unfolds more closely resembles the vogueish domestic thriller, but that trend has already begun to calcify a mere seven years after Gone Girl.

The Woman in the Window is so preoccupied with signalling itself as part of the voyeur genre that it fails to do anything interesting with it. After an hour and 45 minutes of tedious viewing, I was left wondering if the couple across the street would have provided more entertainment. I guess I’ll have to keep watching.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks