Vice is so determined to make a political point it ends up patronising its audience

Adam McKay's brash and noisy attempt to fuse documentary and narrative film never coheres, argues Clarisse Loughrey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the rattle and roar of Trump’s America, only the loudest can now be heard. Vice, the awards-darling biopic of Dick Cheney’s life, is an undeniable product of this climate.

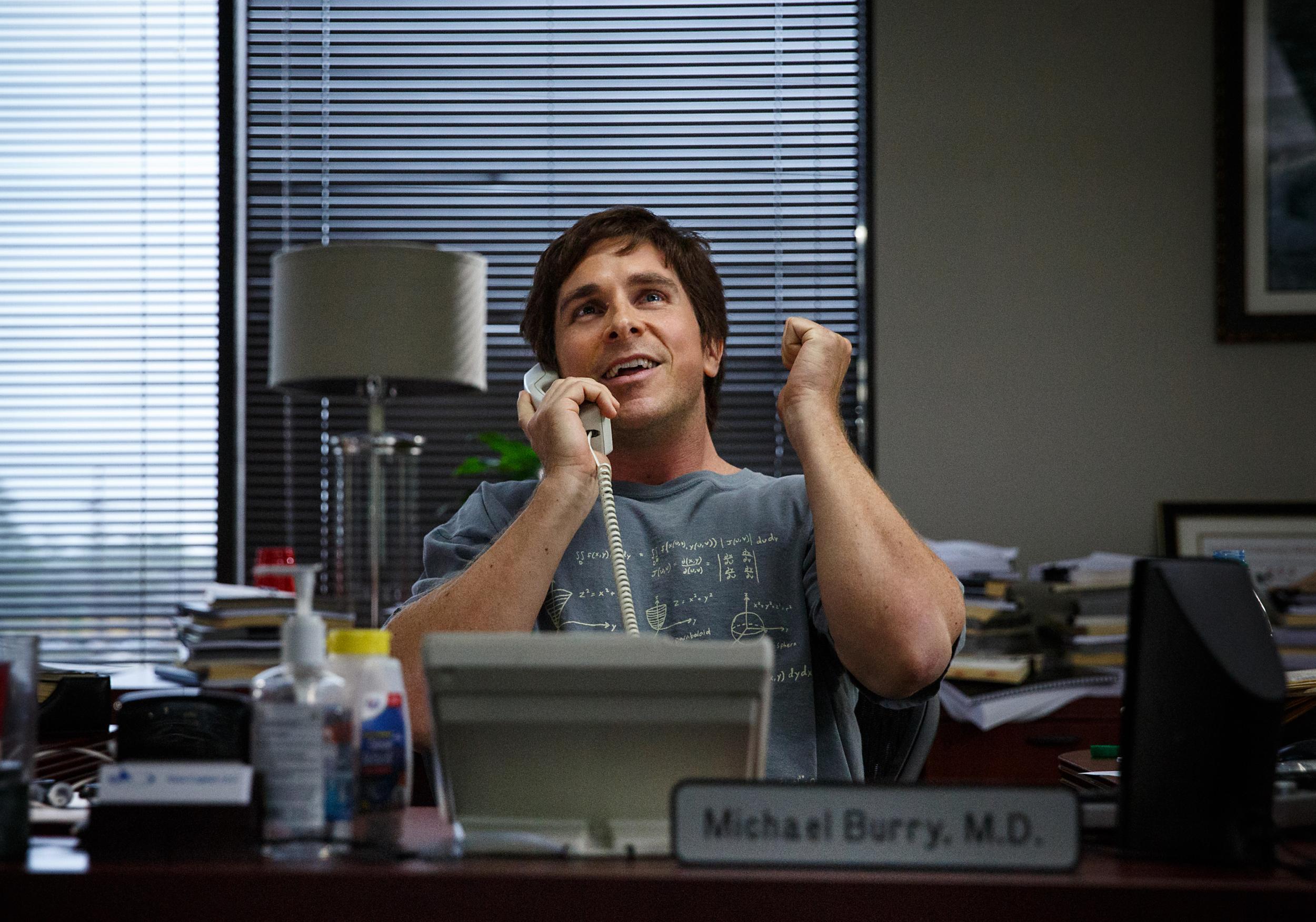

A comedy-drama stacked with top-tier performances – Christian Bale as Cheney, Amy Adams as his wife Lynne Cheney, Steve Carell as Donald Rumsfeld, and Sam Rockwell as George W Bush – the film sees Adam McKay recycle many of the bolshy cinematic techniques he used in 2015’s look at the financial crash, The Big Short.

All subtlety is thrown out the window, as the film opens with a declaration that this is a true story. Or “as true as it can be given that Dick Cheney is known as one of the most secretive leaders in recent history. But we did our f***ing best.”

From there, Cheney’s political career is chronicled from his early days as a college drop-out to his ascendancy to the role of vice president under George W Bush. But there are few of the trappings of traditional biopics. McKay is interested less in unveiling the mind of a man like Cheney than in using the film to draw a line between his manipulation of the unitary executive theory (an interpretation of American constitutional law that gives the president king-like powers), and Trump’s own disregard for the limitations on his power.

McKay is aided in his cause by the film’s narrator, played by Jesse Plemons, on hand to underline and explain whatever point isn’t already blindingly obvious to audiences. Any metaphors are diligently spelled out. The film cuts to a lion hunt when Cheney is acting like a predator, and to a fishing line when we see him reel Bush into his machinations.

Vice wields its political activism like a sledgehammer and, though McKay’s motivations are understandable, it’s hard to see much merit in the approach. The film has found its audience – it’s earned a decent $36m at the US box office so far – and Bale is a frontrunner for the Academy Award. Yet critics have called into question the effectiveness of McKay’s mix of humour, political portraiture, and stern lecturing. As Time’s Stephanie Zacharek writes: “McKay seems to think we can’t be trusted to grasp what he sees as Cheney’s Machiavellian villainy unless he spells it out in cartoon language.”

Do audiences really need to be patronised to this extent? Perhaps. After, all desperate times do call for desperate measures and, as a wake-up call to the American left, the film serves as a bucket of water over the head to those who’ve attempted to rehabilitate Bush’s reputation as of late, gushing over photos of him sharing candy with Michelle Obama and growing nostalgic for a time when Republican presidents at least showed basic manners. Vice responds by directly placing the burden of 4,500 dead American soldiers and 600,000 dead Iraqi civilians on Bush and Cheney’s shoulders. The reminder will likely be sobering, for some.

However, it comes at the expense of alienating so many others. Narrative film is unsuited for this kind of direct, borderline-aggressive didacticism, that the saliency of the film’s political points is drowned out by its stylistic forcefulness. Vice is so noisy with ideas, there’s almost no room for sober reflection on their meaning.

The film’s brashness can be traced back to McKay’s comedy origins, from two seasons as head writer on Saturday Night Live to 2004’s Anchorman and 2008’s Step Brothers. It was in 2010’s buddy-cop comedy The Other Guys that the political activism of his work kicked in, with the closing credits providing a series of statistics about the economic crisis of the time.

McKay’s thinking is surely that comedy is a perfect vehicle for political education, humour making us lower our guard when it comes to unappealing topics. In Vice, however, such an approach is undermined by the chastisement the film delivers in its closing credits. After covering its own back by having a Trump supporter angrily accuse the film of “liberal” bias, the camera pans to a woman bored by the whole proceedings who says she’d much rather go watch the “lit” new Fast & Furious film. Not only is the moment plainly condescending, but it smacks of hypocrisy when it’s tacked on to the end of film that explicitly uses comedy to make its sober messaging more palatable for audiences.

More crucially, Vice continually talks down to its audience by making the same points twice. The film portrays Cheney’s misdeeds while also plainly stating Cheney’s misdeeds, rather than trusting the narrative to do the work needed. And the narrative really is strong enough on its own: the story of an opportunistic ne'er-do-well who climbs his way to unprecedented power, where he betrays a loved one in order consolidate his legacy (Cheney allows one daughter to pursue an anti-gay marriage stance to advance her political career despite his other daughter being in a same-sex marriage).

But that isn’t enough for McKay, and all of the film’s stylistic flourishes – from a scene where Cheney and his wife address each other in weighty Shakespearean monologues to the film’s closing moments, in which the former vice president directly addresses the camera and declares “I will not apologise for doing what had to be done” – are mere repetition.

They’re the equivalent of a flashy transition in a Powerpoint presentation: unnecessary razzle-dazzle that betrays a lack of confidence in the argument itself. At times, it feels like McKay doesn’t believe that traditional storytelling has much to offer political activism.

It’s true that, in times of crisis, radical filmmakers have been more inclined to turn to documentaries and visual essays as a way to speak more urgently to the people. The civil rights movement saw a proliferation of documentaries, such as Take This Hammer (1963), All the Way Home (1957), and Agnès Varda’s Black Panthers (1968). The impulse makes sense, as the documentary, in general, seeks the unadorned truth (how successfully is an entirely different matter) in order to express its message with the greatest possible urgency.

Narrative film, meanwhile, is inevitably more of an exercise in empathy. It is an opportunity to see the world through another’s eyes and to learn from the experience, since narrative film is constricted to the perspective of one or several protagonists, however despicable they may turn out to be. It’s not as direct a conversation with the viewer.

Yet McKay attempts to make it so, in the hope that somehow he can fuse documentary and narrative film into one. In reality, both approaches end up awkwardly overlapping, begging the question as to why McKay didn’t simply produce a documentary on the topic in the first place.

Twenty-eighteen didn’t exactly come up short in politically slanted filmmaking, and it’s worth noting how many narrative works made points just as potent as Vice without resorting to its soapbox approach. Sorry to Bother You used absurdism to argue its case, and suggested that the dystopia we fear has already long been a reality under capitalism. The Death of Stalin used one historical crisis as a stand-in for any number of contemporary crises, making a larger point about the weakness of men who seek power. BlacKkKlansman may have slipped into documentary territory in its final moments, but its purpose was more distinct, utilising footage from Charlottesville as a reminder that the racism of its 1970s-set story is not an artefact of the past, but a continuing reality.

These are all films that understand how powerful empathy can be as a storytelling tool, films that understand that by offering us different perspectives, we’ll be able to draw the parallels for ourselves and better understand our own world. Really, does the message need to be spelt out?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments