Variations on the theme of Vivaldi

This year, two movies about the great Baroque composer are due to be released. Why the sudden fascination with a man who died 270 years ago? Jonathan Brown reports

You wait for years for a decent biopic about the musical genius Antonio Vivaldi and then two come along at once. Nearly five years after it was first talked about, a cinematic exploration of the secret life and times of the composer living among the unwanted children of the fallen women of 17th century Venice is finally about to begin.

The announcement that filming will commence in September this year for the long-awaited homage to the The Four Seasons' creator has coincided with news that work on a second project also probing the private world of the grandfather of Baroque is due to start soon. Movie industry insiders are already talking about the prospect of "duelling violins" at the box office and the welcome return of the classical music biographical genre, the best-known example of which is the Oscar winning Amadeus.

The British actors Max Irons, son of Jeremy Irons and the star of Little Dorrit, Claire Foy, are already reported to have signed up to one of the projects. They are the latest in a series of names including Gerard Depardieu, Joseph Fiennes and Jacqueline Bisset to be linked to the film, which will be shot in Venice, Germany, Hungary and Bruges, according to The Hollywood Reporter.

Meanwhile, The Illusionist's star Jessica Biel, the British acting grandee Ben Kingsley and the German-born violin virtuoso David Garrett have been linked with the second Vivaldi biopic.

While the first will focus on the composer's work with the orphans of the Ospedale della Pieta, a musical orphanage for poor and illegitimate children where baby girls were passed through a hatch in the wall, the second will concentrate on the musician-priest's inner battles to preserve his vows of celibacy in the face of love. Both will be set to a backdrop of his finest music.

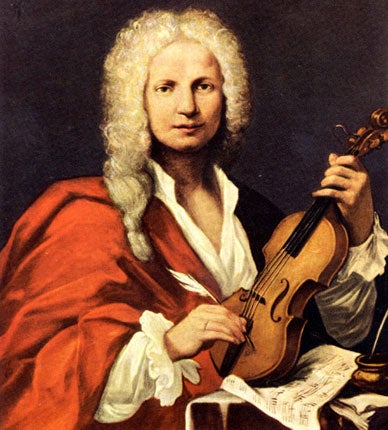

Vivaldi's reputation has – until now – rested primarily on his unique attributes as a composer. But recent years have seen the attention switch to his unconventional personal life. Although he may not have been quite the "sex-obsessed rock star" of his age as suggested in some of the early publicity surrounding the movie projects, his life was certainly the stuff of feel-good screenplay. Glamorous and beguiling to those who met him, Vivaldi was known to his fans as "il prete rosso" or "the red priest", on account of his shock of flame-coloured hair.

Yet, for all his genius and the adoration it brought him, he preferred to live the quietest of lives, residing for 40 years with his parents and teaching violin and conducting the choir and orchestra at the Ospedale della Pieta.

Four centuries before Gareth Malone cajoled mumbling teens into a crack singing unit for The Choir, Vivaldi was doing something considerably more spectacular with the abandoned youngsters who were delivered into his care.

The Pieta became a must-see stop off on the Grand Tour circuit of the travelling nobility, although the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau found himself "desolate" after watching Vivaldi's girls perform and then meeting them. Many were scarred or disfigured through poverty and disease, yet a significant number of his protégées went on to become acclaimed musicians in their own right.

Describing the experience, Rousseau later wrote: "M le Blond introduced me to one after another of those famous singers. 'Come, Sophie' – she was horrible. 'Come, Cattina' – she was blind in one eye. 'Come, Bettina' – the smallpox had disfigured her. Scarcely one was without some considerable blemish... I was desolate."

By the end of their meeting he had changed his tune. "My way of looking at them changed so much that I left nearly in love with all these ugly girls," he remarked.

Vivaldi's name was romantically linked with at least two women during his lifetime. There was Paulina Tessiere, his personal assistant at the Venice Opera and her sister, Anna Giro, one of his singing pupils. But scholars insist that, despite the licentious reputation of the Italian city state, the relationships amounted to nothing steamier than that of devout teacher and dedicated pupil.

Although hailed for his talents by nobility – not least by his patron, the Emperor Charles VI and Louis XV, for whom he wrote a wedding cantata – by the final years of his life he was virtually penniless. And while his reputation for sexual probity remained intact, his musical legacy by contrast dwindled as rapidly as his wealth in the immediate decades following his death in 1741.

The rediscovery of his work – both figuratively and literally, in case of the uncovering of a lost archive in a monastery in Piedmont including 14 previously lost folios – occurred last century.

By the 1980s his work was popularised on radio and television and, most lucratively, in the interpretation of his greatest piece, The Four Seasons, by the violinist Nigel Kennedy.

Last year, the discovery of another long-lost work at the National Archives of Scotland, brought back to his native land by Lord Robert Kerr, was the subject of international media coverage when it was played for the first time in its entirety for 250 years.

Force behind the revival

* If one man is responsible for the ubiquity of Vivaldi's work in restaurants, telephone hold music, elevators and the world's concert schedules it is Alfredo Casella.

The Italian-born composer and friend of Debussy, Stravinsky and Mahler organised the historic Vivaldi Week celebrated in Siena in 1939 – an event backed by the poet Ezra Pound.

The rekindling of interest in Italian Baroque followed nearly two centuries in the musical wilderness for Vivaldi. The war interrupted the renaissance but the publication of a complete works continued following the defeat of the Axis powers.

While Casella, who died in 1947, did not rediscover The Four Seasons he can lay claim to having revived the composer's most popular choral work, the Gloria in D. Twentieth-century British audiences were treated to their first taste of Vivaldi at the Festival of Britain in 1951.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks