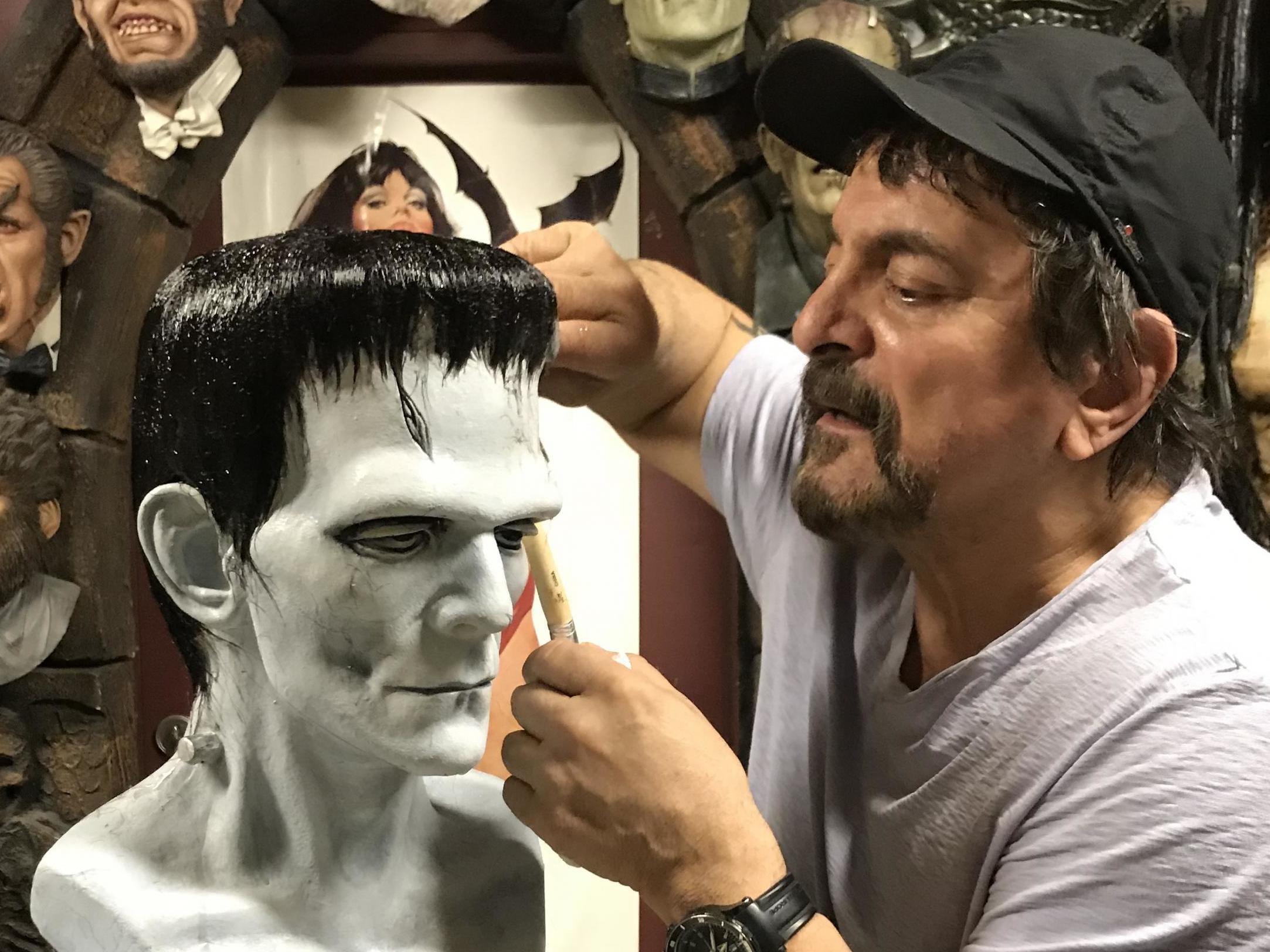

Horror effects icon Tom Savini: ‘My work looks so authentic because I’ve seen the real thing’

The 73-year-old master of prosthetics and gore in films such as Dawn of the Dead and Friday the 13th tells Thomas Hobbs some of his secrets and how being a photographer in the Vietnam War shaped his life

Whether it’s Kevin Bacon unexpectedly getting an arrow through the throat while lying in bed in Friday the 13th, Ted Danson’s waterlogged walking corpse in Creepshow, or a zombie getting the top of its head sliced off by a helicopter blade in Dawn of the Dead, Tom Savini is responsible for some of horror cinema’s greatest moments. Yet not everybody realises that a lot of this iconic gore was inspired by the special effects guru’s traumatic time serving as a field photographer in Vietnam.

“I saw some pretty horrible stuff,” the horror legend, now 73, tells me soberly. “I guess Vietnam was a real lesson in anatomy.” While serving with the US military, Savini learnt details such as the way blood turns brown as it dries or how our bodies lose control of the muscles when we die. “This is the reason why my work looks so visceral and authentic,” he adds. “I am the only special effects man to have seen the real thing!”

Many people would have lost their minds when confronted by such suffering, but Savini, who as a child created masks and fake blood in his bedroom after being inspired by classic 1950s horrors like Man of a Thousand Faces and Creature from the Black Lagoon, used this childhood passion as a way to disconnect. “What saved me from going insane in Vietnam was looking at these horrible scenes like they were a special effect someone else had created,” he explains further. “I tried to disconnect from the horror and wondered how I could recreate it as a special effect myself.”

That’s not to say these experiences weren’t incredibly damaging: “To do what I was doing as a photographer, well, you had to switch off your emotions, and I guess they don’t just come back on immediately afterwards. When I got back home I had PTSD, my marriage went down the toilet and [for a long time] I was an emotionless zombie, but it somehow set me on the path for a career in the movies.”

Upon his return to his home town of Pittsburgh, Savini quickly landed a job as a makeup artist on Deathdream, an underrated, low-budget 1974 horror about a soldier who returns permanently altered from his experiences in Vietnam. The parallels were obvious and Savini was rarely out of work from that moment onwards. Throughout the 1980s, he pioneered a new visceral approach to horror special effects and animatronics, becoming a regular collaborator with late visionary horror director George A Romero, shaping the colourful kills in Romero classics such as Martin, Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, Knightriders and Creepshow.

Although a lot of Savini’s work appears brutal, there’s a goofiness that underpins it, which is accentuated by over-the-top comic-book death sequences and killers who look like otherworldly bogeymen. In Creepshow (1982), for example, there’s a hick (played by author Stephen King, no less) whose flesh slowly turns into weeds, a bizarre vision that somehow manages to be both comically surreal and skin crawling. “I was seen as the king of splatter, but for Creepshow I finally got to design what was in my dreams!” Savini says.

His playfulness stretches back to early experiments with fake blood as a form of escapism to forget about the rigidness of Catholic school. “My work is a matter of pulling together all the right materials and creating a magic trick, something I’ve been doing since I was a boy,” he says. “You are fooling people into believing in the illusion. I guess me and Romero wanted to be magicians of murder. If you see our names on the cinema billboard then you know you’re in for a really great magic show that will make you laugh but may also give you nightmares.”

One of the pair’s greatest collaborations, 1985’s Day of the Dead, recently celebrated its 35th anniversary. The film focuses on a group of scientists and military survivors who are holed up in an underground facility as the zombie apocalypse wreaks havoc outside. The way it delves into the toxic claustrophobia of self-isolation and its portrayal of figures of authority hiding from the chaos of the world feels prescient, calling to mind claims that President Trump hid in a White House bunker to avoid angry protestors. But it is the special effects that really make the film – the third in Romero’s Undead trilogy – fly. One sequence, which shows the villainous Captain Rhodes ripped limb-from-limb by a group of zombies, his vocal chords straining as his head is torn off, is difficult to forget.

“I learnt that people decompose differently depending on who they are or where they were when they died. So I tried to make every single zombie in Day of the Dead look like they were at a different stage of death. Romero let me be as ambitious as I wanted!” Savini recalls affectionately. “That film was my masterpiece. It was this big new adventure of killing people in outlandish ways. I would say 80 per cent of the work I did with Romero was improvised. If he liked an effect, he would wink at me and make this cricket sound. We had our own language.”

But that’s not to say Savini looks back at all their work together through rose-tinted glasses. “The blood I used in Dawn of the Dead was horrible,” he claims. “It looked good in the bottle, but it photographed like melted crayons and had this awful pink colour. Thankfully, just before I worked on Friday the 13th, Dick Smith [the legendary special effects man who masterminded the effects for Regan in The Exorcist] told me his blood formula and everything was okay from then onwards.” So what was the formula, I ask. “Oh, corn syrup mixed with yellow and red food colouring.”

Savini also looks back fondly on his work with Italian horror auteur Dario Argento, particularly on 1993’s Trauma, a film about a murderer who exclusively decapitates his victims. He says the film taught him how to improvise when things don’t go to plan. “Piper Laurie was claustrophobic, so we couldn’t make a cast of her head. So I ended up putting her on a stool underneath the flooring of the set and spun it around so it looked like her head was rolling off her shoulders. From that day onwards, Argento called me the ‘volcano of the mind’. He was the greatest visual stylist I ever worked with.”

Yet Savini admits that some of his own effects might have gone too far, particularly in 1980’s Maniac, a video nasty about a loner who sadistically kills women. The movie even features Savini, who appears as a victim, getting his head, a prosthetic that had blood filled condoms inside, blown off with a shotgun. “They originally wanted really extreme sexual murders, but I said no to some of it, so what you see in the film is actually a lot less than what was planned!” He doesn’t seem to relish the memories of being the effects lead on The Burning (1981), a slasher flick which was Harvey Weinstein’s first film for Miramax. “That film was so rushed. Harvey was creepy and loathsome, even back then. I had no idea he was doing those things.”

It’s worth noting that Savini has also enjoyed a varied career as an actor, utilising his love for fencing and motorcycles for badass roles in films such as Dawn of the Dead (1978), From Dusk Till Dawn (1996) and Machete (2010). In these movies, he has the look of a man who could kill you with just a stare. “I model myself on Charles Bronson,“ he says of his acting approach. ”I want to be the epitome of the macho man and the strong, silent type. You either have it or you don’t. You can’t fake it. I guess I miss when men were men. You don’t have a Robert Mitchum today and that’s a shame.”

Approaching his mid-seventies, Savini’s main passion nowadays is teaching students how to become special effects maestros via his celebrated make-up effects programme at the Douglas Education Center in Pennsylvania. Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, the course teaches students how to create natural life-like effects without the need for CGI. “You name a big studio movie from the last 15 years and one of my students worked on it. At the end of the course, I make them re-design a classic horror character. They’re all like my own Dr Frankensteins!”

Has the course been a way for Savini, whose work has slowed down over recent years, to maintain his CGI-less approach to special effects and keep Hollywood authentic? “When I hear of there being more practical effects in the new Star Wars or Evil Dead,“ he says, ”it makes me happy. There seems to be a desire to actually make things again. If I’ve played a role in that then that’s really nice.” As for his own legacy, and how he would like to be remembered, Savini concludes: “My father could do everything! He was a plumber, an electrician, a carpenter, a shoemaker. I always wanted to emulate him. Whether it is directing, acting or doing make-up and prosthetics, I just want to be remembered as someone who could do many things well.” I suspect he will be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks