Tobe Hooper: How the director created horror's ultimate serial killer

‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’ director who died last month leaves a lasting legacy with his masterpiece about a family of cannibals

Texas. Chain saw. Massacre. Every word intimidates, but when placed together, they become evocative poetry, an unforgettable incantation of cheap and dirty horror.

As soon as advertisements for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (not to be confused with the 2003 remake or subsequent franchise The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), an unlikely masterpiece about a family of cannibals directed by a pacifist and distributed by the company behind Deep Throat, started appearing across the country in 1974, the lexicon of fear forever changed.

The death in August of 74-year-old Tobe Hooper, who co-wrote and directed this movie in central Texas, came only one month after that of George A Romero, a peer who also grew up reading EC comics and the magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland – the common core curriculum of a dwindling class of auteurs who revolutionised genre movies in the 1960s and 1970s.

As with so many aspiring artists who saw the 1968 independent Night of the Living Dead, Hooper was inspired by that movie’s director, Romero, proving that a few friends on a shoestring budget far from Hollywood could turn a visceral little movie into a reputation-making hit.

Both Living Dead and Chain Saw earned moralising reviews that likened their violence to pornography – Harper’s Magazine called the latter a “vile little piece of sick crap”. They also earned decades of passionate devotion from fans. Just as Romero breathed life into the lurching zombie, Hooper created the first great masked serial killer in modern American horror.

Anticipating the slasher boom that would begin four years later with Halloween, Leatherface (played with hulking abandon by Gunnar Hansen, who died in 2015) hunted his prey with ferocity and panache, using a hammer, a meat hook and, of course, a chainsaw. Living Dead emboldened a generation of horror masters, but Chain Saw terrified them the most.

Wes Craven, who died two years ago, said it was so intense that it felt like a snuff film. John Waters and John Landis both cited it as the scariest movie they had ever seen. Ridley Scott watched a screening of it before filming Alien, to help him ratchet up the terror of his movie. Romero said he avoided Chain Saw when it came out because the title seemed too tawdry, which is like Prince finding the sexuality of your music a bit much.

And yet, that is where the reputation of Chain Saw obscures some of its greatness. What really distinguishes it is not its brutality and ruthlessness, but its stunningly realised aesthetic. Its characterisations contain as much empathy as evil, and its finest moments mix the beautiful with the vicious. It’s the most persuasive proof captured on film that the tools of exploitation can make transcendent art.

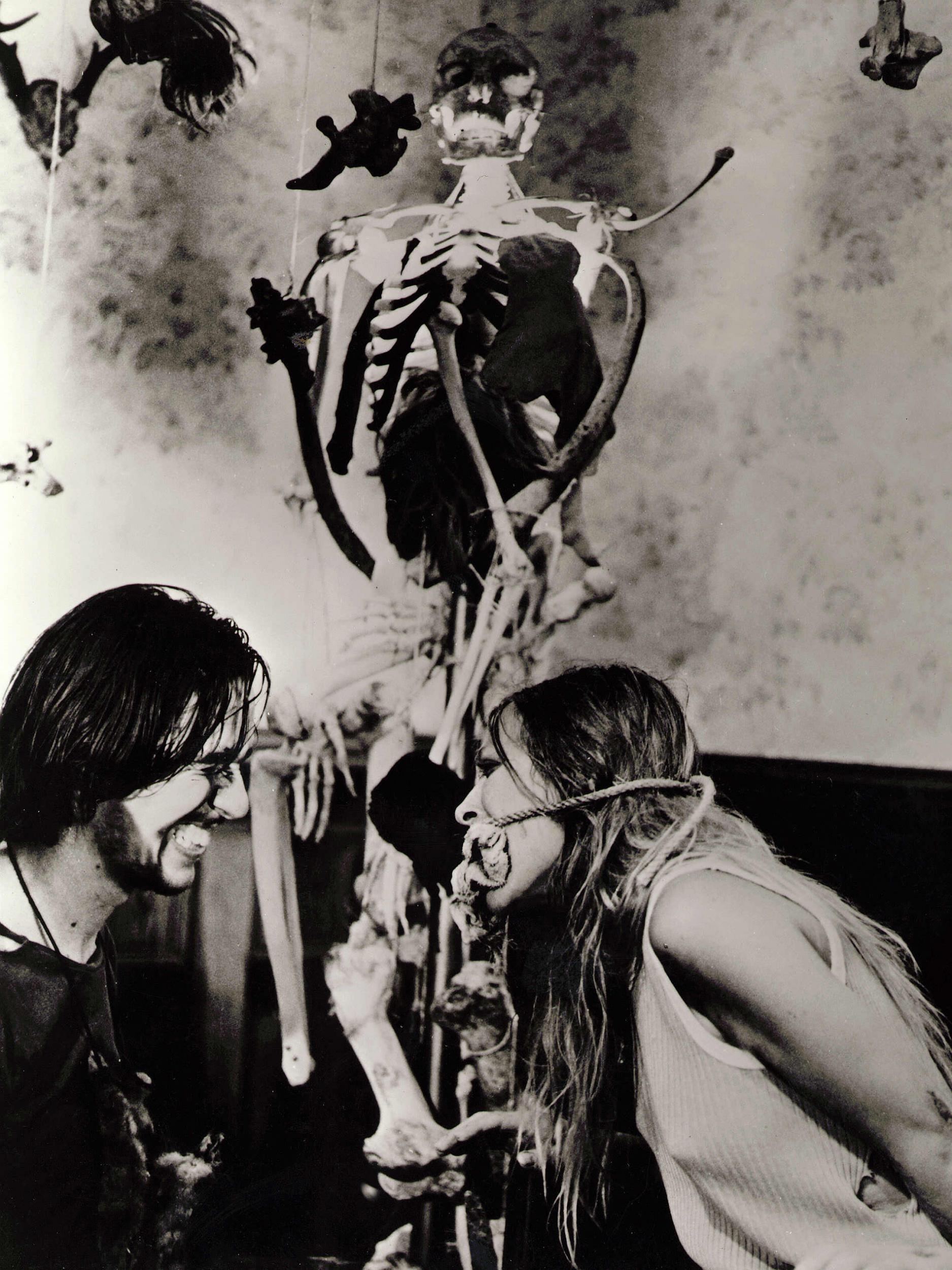

As is usually the case with grindhouse marketing, the title is deceptive. By the standards of horror, there’s no massacre. Only five people die – much fewer than in the sequels and remakes. Hooper relied on suspense more than gore, staging the kills with nary a drop of blood. He didn’t show, for instance, a woman’s back impaled on a hook, but the bucket below her, letting viewers make the connection to this container’s gruesome purpose.

Typically, when horror fans try to make you take a scary movie seriously, they resort to politics. And while Chain Saw has often been explained as a brief for vegetarianism, it could just as easily be used as a metaphor for our current moment: It focuses on anxious red-state family members whose jobs at a slaughterhouse are made obsolete by technological innovation (the air gun) and who lash out at dismissive outsiders. If you want to explore the theme of white working-class resentment, it wouldn’t be difficult.

But Hooper made an intimate movie that has always seemed more personal than ideological. Its last act is essentially a single set piece about a severely dysfunctional family at dinner, with battling brothers fighting for the approval of a damaged patriarch.

“Those family dinners can go very wrong,” Hooper told me in an interview, recalling that his parents constantly fought before getting divorced when he was eight. “I saw some things growing up that were bizarre and wrong.”

Hooper didn’t sugarcoat the evil of the killers, but when he lingered on Leatherface’s eyes behind his mask, you saw fear. An inarticulate simpleton, he gets bullied by his obnoxious brothers, forced to make them dinner. Their taste may be unorthodox, but who knows what years working in a slaughterhouse will do to your palate?

When planning the movie, Hooper and his fellow writer Kim Henkel watched Frankenstein; their film, like that classic 1931 Universal horror picture, extends some sympathy to the monsters.

They are certainly far more compelling characters than the young victims – the wheelchair-using Franklin is the ultimate example of the common horror character so intentionally annoying that you secretly cheer his death.

Hooper baffled many by describing his movie as a comedy, but you can detect its sense of humour in the way the killers come off as fools quibbling in a mundane family comedy, a sensibility that became far more overt in his sequel, an entertaining farce that disappointed fans expecting something as terrifying as the original.

All great horror movies lose something in the second viewing. Once you’ve seen the alien burst out of the chest, or discover the truth about Norman Bates’ mother, a certain pleasure – an essential one to the genre – is gone. While watching The Texas Chain Saw Massacre for the first time remains a singular adrenaline rush, it’s the rare horror movie that just keeps getting better every time I see it.

What’s lost in surprise is made up by new details noticed: the gothic juxtapositions of colours, or the ominous tracking shot underneath the swing as a victim approaches the killer’s house. When Steven Spielberg met Daniel Pearl (the Chain Saw director of photography) on the set of 1941, he stopped shooting and asked how that shot was pulled off. It’s one of many moments when Hooper turns the vast blue Texas sky into a terrifying backdrop.

In the seminal final shots of Chain Saw, the colour of the landscape changes, turning hot yellow in an instant: an abrupt shift that belongs more to dreams than any real-life dusk. The nightmare ends with Leatherface holding a roaring chain saw aloft and twirling – a dance of death whose gracefulness is the movie’s final shock.

© 2017 New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks