The strained making of 'Apocalypse Now'

Dead bodies, heart attacks, wild parties, cocaine binges, Marlon Brando's belly and breakdowns. Thirty years on, Robert Sellers revisits the making of 'Apocalypse Now'

If things had worked out differently, Apocalypse Now would have been directed by George Lucas in 1970, guerrilla-style in Vietnam itself, while the conflict was still raging. Rightly, no studio would finance such an exploit, for fear that Charlie might dislodge the film-maker's lower intestines with a well-aimed bazooka shell. Francis Ford Coppola's vision was far greater, far more artistic and far more bonkers. As he later raved during a Cannes press conference, his film wasn't about Vietnam, "It is Vietnam!"

It was expected to be a 14-week shoot in the Philippines, beginning in the spring of 1976, but logistics, weather and general disasters conspired against the film. Worse, Coppola fired his leading man, Harvey Keitel, after two weeks, replacing him with Martin Sheen, who was then nursing private demons of his own, namely booze. When Sheen arrived, he found chaos. Coppola was writing the movie as he went along and firing personnel, people were coming down with varioustropical diseases and the helicopters used in the combat sequences were constantly recalled by President Marcos to fight his own war against anti-government rebels.

As for the crew, they worked hard – and boy, did they party hard. Doug Claybourne was brought in as production assistant. As a Vietnam vet, he was one of maybe two or three people working on the movie who had actually been involved in the war. "At the hotel where the crew were based, it was party heaven. We'd have a hundred beers lined up around the swimming pool. There were people diving off the roofs, it was crazy." Then a typhoon hit, and the whole production was temporarily shut down.

After a month regrouping at his base in San Francisco to rethink his battle plan, Coppola returned to the jungle. Some of the crew mutinied and didn't go with him. Sheen did, somewhat reluctantly. "I don't know if I'm going to live through this," he told friends.

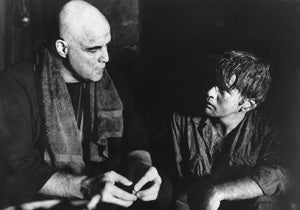

Work now began on the sequences revolving around Marlon Brando as Colonel Kurtz, the Green Beret general who goes Awol and is hunted down by his own side. During shooting on the set of Kurtz's compound, a shocking discovery was made. One morning, Sheen's wife took the co-producer Gray Frederickson to the temple set, which was strewn with garbage and smelt terrible. "You've got to clean this up," she demanded. "It's a health risk. I won't allow Marty to work here." So Frederickson went to see the production designer, Dean Tavoularis. "They're complaining about you, there are dead rats in there." Looking not very bothered, Tavoularis said, "That's intentional, it gives it real atmosphere." There was a prop guy standing close by who muttered, "Wait till he hears about the dead bodies." Frederickson cried, "What!"

Rumours had been flying around about dead bodies on the set but Frederickson discounted them as ludicrous. Then he was taken to the prop store, located behind a tent where everyone ate dinner, and inside was a row of cadavers all laid out. "You guys are nuts, where did these come from. We've got to get rid of this immediately." "No, no, they'll be very authentic, we'll have them upside down in the tress." Frederickson was livid: "You can't do that!"

They'd got the stiffs from a guy who supplied bodies to medical schools for autopsies. It turned out he was a grave robber. "The police showed up on our set and took all of our passports," says Frederickson. "They didn't know we hadn't killed these people because the bodies were unidentified. I was pretty damn worried for a few days. But they got to the truth and put the guy in jail."

Later, a huge truck showed up and soldiers started loading the bodies inside. "Where do we take these," one of them asked. "I don't know? The cemetery?" Frederickson answered. Turned out they couldn't because nobody was going to foot the bill to bury them. "Oh, don't worry," they said. "We'll dump them somewhere." And they drove away. "I don't know what they did with them," says Frederickson. "So for the scenes in the movie we had extras hanging from trees, not dead bodies."

When Brando arrived, he shocked everybody – he was enormous, maybe 300 pounds. "You couldn't see around him," says Frederickson. This gave Coppola palpitations, as he had envisioned Kurtz as a lean and hungry warrior. Also, what the hell was he going to wear? There was no Green Beret uniform on earth big enough!

Worse, Brando hadn't learnt his lines or done any preparation whatsoever for the role. "Francis had to literally start from scratch with him," says Doug Claybourne. "He had to bring him up to speed on what the thing was about and who the character was." According to his co-star Dennis Hopper, the production was shut down for a week while Coppola read Brando the script out loud. "Nine-hundred people, the cast and crew, just sat and waited!"

One day, suddenly, Brando shaved all his hair off and arrived at the idea of improvising his scenes and letting Coppola's camera capture whatever came out of his mouth. Self-conscious about his killer-whale appearance, Brando also stipulated that he dress in black and for the most part be filmed in shadow. Coppola agreed to steer his camera away from his enormous belly.

Brando wanted nothing to do with Hopper, due to his drink-and-drugs lifestyle; for their scenes together, they had to be filmed separately on alternate nights. Hopper was in a bad way according to George Hickenlooper, who directed the documentary Hearts of Darkness about the making of Apocalypse Now. "Dennis recounted the story to me that Francis came to him and said, 'What can I do to help you play this role?' Dennis said, 'About an ounce of cocaine.' So he was being supplied by the film production drugs that he could use while he was shooting."

Hopper's performance as a crazed photojournalist is, well, crazed. "That's the way he was, on and off camera," says Frederickson. "But he was fun and everybody loved him. There wasn't an edge to his craziness at all. Actually, he's a lot more serious and less friendly now that he's not so crazy." For some of the crew he was also taking his method acting a little bit too far. "Dennis was known at that time for never taking a shower," says Claybourne. "You didn't want to stand too close to him."

Catastrophes plagued the production. Martin Sheen suffered a heart attack. Coppola convinced himself he was to blame and one evening had an epileptic seizure. "We had access to too much money and little by little we went insane," he later confessed. Hopper said, "Ask anybody who was out there, we all felt like we fought the war."

Coppola had more to lose than most. Some of the money being squandered was his own, several million in fact, and he faced financial ruin if the film couldn't be completed. No surprise that he suffered a nervous breakdown, declaring on three separate occasions that he intended to commit suicide.

Apocalypse Now opened in 1979 and is today regarded as a masterpiece. Claybourne recalls helping organise press screenings in New York. "I had all the actors together at the theatre but I couldn't find Dennis. I had to go back to the hotel and I found him in his room, stark naked with his cowboy hat and his cowboy boots on. I said, 'Dennis, it's time to go to the screening, man.'"

Years later, when Hickenlooper made his documentary, most of the stars and crew were happy to talk about the movie, except Brando. Hickenlooper tracked him down to the set of a movie and made his move. "'Mr Brando, we're making a documentary on Apocalypse Now, would you be prepared to do an on-camera interview?'" Brando turned round and stared like death into Hickenlooper's face. "Why are you making a film about that fat fuck, he owes me $2m." Obviously, Brando was having issues with his royalty checks from Coppola. "You tell that fat fuck that if he pays me the two million, you can film me taking a shit." With that, the trailer door slammed shut. Hickenlooper never got his interview.

Robert Sellers is the author of 'Bad Boy Drive: The Wild Life and Fast Times of Marlon Brando, Dennis Hopper, Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson', published by Preface Publishing

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks