The Shining: Heeeere's ... a conspiracy theory

As it is re-released, Jonathan Romney explores the lasting obsession with Stanley Kubrick's classic horror

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's fair to say that Stanley Kubrick's 1980 horror film The Shining is all things to all viewers: a ghost story, a portrait of mental and familial breakdown, a critique of male violence. Some see it as an allegory of the malaise of modern America, or a horror film about horror films. But a coded admission by Kubrick that he was involved in faking the Apollo 11 Moon-landing footage? That's one of the more far-fetched readings that The Shining's many obsessive fans have hatched over the years. And don't be surprised if a wave of even wilder interpretations follows in the wake of both a re-released, extended version of the film and Room 237, a documentary about said fans, in which the Apollo theory is expounded along with other oblique angles on Kubrick's film.

It puzzled many critics when first released: some wondered why the visionary director of 2001 and A Clockwork Orange was messing about with what seemed tawdry scare material, and a Stephen King adaptation to boot. But, since then, The Shining has become one of those films that command intense devotion. In the recent Sight & Sound poll of the greatest films ever, 11 critics (myself included) and eight film-makers included it in their personal Top 10. The latter include The Artist director Michel Hazanavicius and rising US indie auteur Sean Durkin (Martha Marcy May Marlene). Durkin first saw the film at the age of 12 and watches it at least once a year. "It affected me like nothing else. It took the supernatural and turned it into real physical terror," he says.

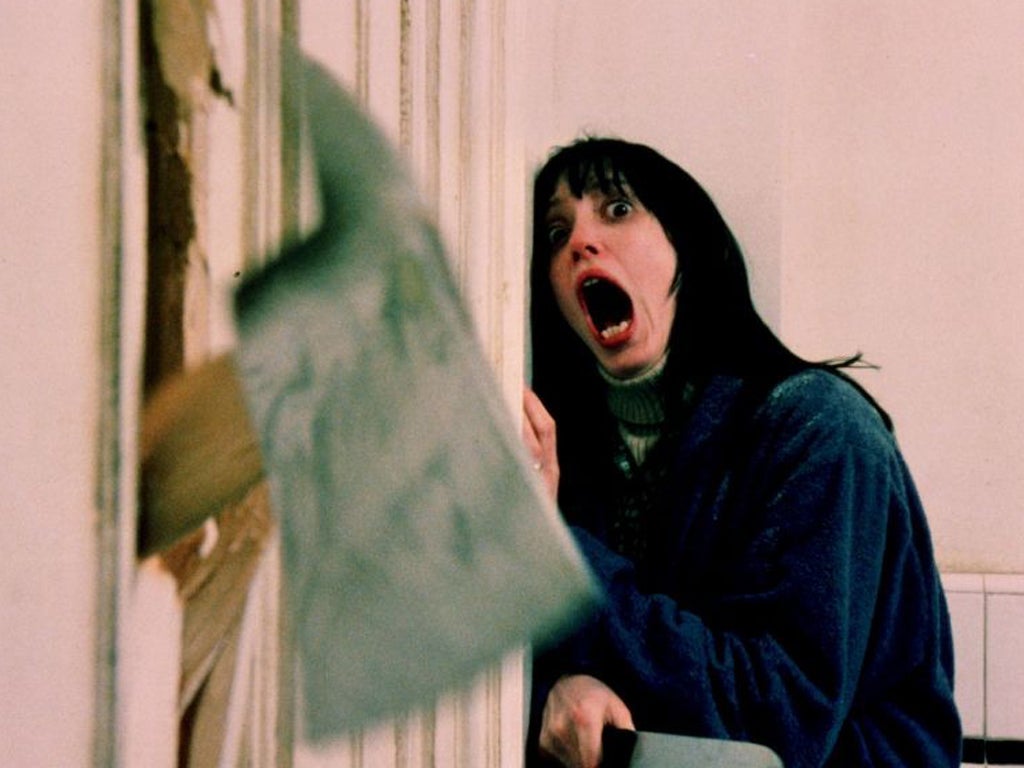

Thirty-two years after its release, The Shining still makes for a nerve-jangling experience. It follows Jack Nicholson's failed, recovering alcoholic writer Jack Torrance, who takes a job as caretaker of the remote, snowbound Overlook Hotel in Colorado and loses his sanity, trying to kill his wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall) and telepathic son Danny (Danny Lloyd) – seemingly spurred on by phantoms that haunt the hotel ballroom in a thé dansant of the damned. There's more to it than that, of course – although the film never explains quite what that "more" is. Is Jack suffering the malign effects of cabin fever, or a dramatic case of the DTs, or has he (as the ineffably eerie final shots suggest) in some uncanny sense "always" been caretaker at the Overlook? British audiences can now mull over the film's full resonance as they watch the original version that was trimmed by Kubrick after its initial US release. (This version, seen on UK television but never theatrically here, is 24 minutes longer than the familiar European cut.) It contains more material showing Danny and Wendy (who emerges more fully as a character), more about the family's troubled history and more of the ghoulish visions. (Kubrick's original coda showing Wendy in hospital remains missing from this cut.)

With or without the extra footage, The Shining is a dense, elliptical film that tends to set off complex exegetical trains of thought in its fans. In Room 237 – named after the suite where Jack has a hair-raisingly nasty encounter – US documentarist Rodney Ascher records a number of outré but erudite takes on the film. The idea that Kubrick was part of a conspiracy to fake Apollo 11 footage is the wildest, but theories about the Overlook's paradoxical geography, or the presence of Holocaust themes, or the idea that the film is really about the massacre of the Native Americans … well, it's not such a jump to buy those hypotheses. They're just the tip of the iceberg – Ascher tells me of another truly arcane theory that the film is really about America's abandonment of the gold standard, based on the fact that much of the film's action takes place in the hotel's opulent Gold Room.

But what is it about The Shining that sends people into such interpretative tailspins? The film's unsettling tone and densely detailed visuals make you unusually attentive, says Ascher. "It's a very entertaining film. People love to watch it – and while they're there, they have time to notice the carpet patterns and the pictures on the wall. It leaves you unbalanced – it's hard to say at what point things stop making sense."

It's as if individual viewers end up feeling that they have "the shining", the name given to Danny's telepathic insight, which allows them – and them alone – to see what the film is "really" about. "If you're an expert in the history of World War Two, and you start to see allusions to the war, you feel you have the toolkit that allows you understand what he's trying to do."

Above all, says Ascher, the film is impeccably nightmarish. He first saw it when he sneaked into a cinema, aged 10. "I only lasted 10 or 15 minutes before I slunk out because I was so frightened. It feels like this film is going to be a judgement on mankind. It's not the story of a little family; they're sort of proxies in a supernatural conflict of biblical proportions."

Famously, Kubrick's adaptation found little favour with Stephen King, who objected to the director's streamlining of his highly involved 400-page novel. Kubrick fans often feel that King didn't understand the potential of his own material – as evidenced by the prosaic TV mini-series remake he oversaw in 1997. As novelist and horror expert Kim Newman puts it: "Kubrick had better instincts than King. What's scary is the irrational, and King always tries to explain too much."

The Shining has an ambition and a seriousness that transcend the common run of the horror genre – routine chillers tend not to use modernist scores by composers such as Bartok and Ligeti. Even so, it unmistakably is a horror film, and shouldn't be underestimated as such. "It does things that horror films aren't supposed to do," says Newman, "but it regularly comes up in polls as one of the most frightening of horror films. There's nothing on record of Kubrick saying, 'This isn't a horror film', as William Friedkin did about The Exorcist."

Personally, I'm with the camp that sees The Shining as partly a story of cinema and the strange things it does to our minds: Kubrick's co-writer, novelist Diane Johnson, put her finger on it when she said, "In a certain sense, it's the hotel that sees the events; the hotel is the camera and the narrator." After all, cabin fever, which drove a previous Overlook caretaker to murder, is defined by hotel manager Ullman (Barry Nelson) as "a claustrophobic reaction that can occur when people are shut in together over long periods of time". Like two hours in a cinema, perhaps?

The unsettling glow of The Shining hasn't dimmed – nor will it, whatever vagaries the brand may undergo. Next year, Stephen King publishes his novel Doctor Sleep, which takes up the story of Danny Torrance as an adult, still a telepath and now helping young protégés to fight the powers of darkness. "If his remake didn't water it down, I don't see how the book is going to," comments Ascher. More worryingly, it was reported this year that Warner Bros is considering a prequel to The Shining, dealing with events at the Overlook before the Torrances' stay there. But lovers of Kubrick's film don't need any more information about the case of murderous caretaker Delbert Grady, or the mysterious events of 4 July 1921. Our imaginations, spurred by a master film-maker, have long been at work on those questions. And – as Room 237 shows – stranger questions still.

'Room 237' is released on 26 Oct; 'The Shining' is re-released on 2 Nov

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments