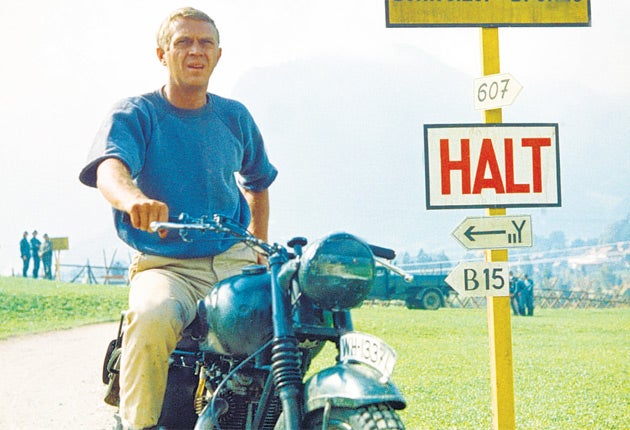

The real Steve McQueen

Hollywood's king of cool is being celebrated in a new season at the BFI. Geoffrey Macnab uncovers the reality behind the action man

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The posthumous "king of cool" is how Steve McQueen is routinely described by his fans today. Thirty years after McQueen's death, the reputation of the star of The Great Escape, The Magnificent Seven, Bullitt and The Getaway hasn't been usurped by any of his successors. No subsequent male lead has managed to be quite as cool as McQueen.

It's not for want of trying. From Die Hard onward, Bruce Willis has striven forlornly to emulate McQueen's laconic screen image. Kevin Costner clearly modelled his persona partly on that of the equally close-cropped and undemonstrative star. Alec Baldwin was another McQueen pretender, even taking the star's old role in an ill-fated remake of The Getaway. But none has come close to McQueen's mix of machismo and unflappability. He was only 50 when he died of cancer. Unlike Paul Newman or Robert Redford, he didn't become crumpled with age or take on the character roles that would diminish his original aura.

The irony is that McQueen really didn't think he was a very good actor – one reason why he was so undemonstrative on screen. "He always said he wasn't an actor, he was a reactor. By that he meant that he didn't want to be lumbered with speaking plot. He wasn't sure he could do it," the Briton Peter Yates, who worked with him on Bullitt, recalled.

McQueen's solution was to pare down and down: to aim for the most minimalist style he could. He is the antithesis to a star like James Cagney, who was in audiences' faces, demanding their attention with his motor-mouthed delivery of dialogue and expressive physical gestures. Nor, although he studied with Sanford Meisner (one of the top Method acting coaches) and effortlessly projected rebelliousness, does he have the soul-searching, neurotic quality of a Montgomery Clift or a James Dean. He isn't the monolithic John Wayne type either. Actors who try to imitate him risk being dull. They don't have his eyes or intensity.

"Steve was the ultimate movie star. He had what they refer to as the X-factor. Well, it's sex appeal, that's what it is. He had enormous sex appeal," Robert Vaughan (his co-star in The Magnificent Seven) said of him.

McQueen was unusual among action stars in that he appealed equally strongly to male fans, who relished his feats of derring-do on motorbikes or in cars, and to women, who sensed a vulnerability behind the swaggering persona. "I think it's safe to say that it would have been impossible not to fall in love with Steve," Ali McGraw, who began a turbulent love affair with McQueen during the making of The Getaway, recently told Vanity Fair.

For all his self-possession on screen, McQueen had a violent temper and a reputation as a rebel. In his early roles, a sense of barely suppressed rage is always evident. McQueen had been abandoned as a kid by his stunt-pilot father. He was a troubled adolescent who often fell foul of the law, fought with his stepfather and spent time in reform school. His time in the marines taught him the restraint and discipline he always seemed to convey in movies.

Scan McQueen's filmography and what is apparent is that, outside the films that are shown on TV regularly (The Great Escape, Papillon, The Getaway, The Magnificent Seven, Bullitt and one or two others), there is a lot of dross. The Blob (1958) may be a cult film but it doesn't show off McQueen to advantage – it's hard to maintain your cool when your co-star is a mass of flesh-eating gunge. His breakthrough Never So Few (1959), his first film with John Sturges (later to direct him in both The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape) is a dreary war picture.

"His entire modern, 21st-century appeal seems to be down to six or seven particular movies," says Tony Earnshaw, curator of the BFI season, Steve McQueen: Hollywood Nonconformist. "I've always felt that he was a far better character actor than people gave him credit for but he became subsumed within this peculiar persona."

It's a moot point how nonconformist McQueen really was. His choice of projects was often very conventional indeed. Contemporaries talk about his outrageous scene-stealing antics with his hat and gun during the making of The Magnificent Seven, designed to ensure that audiences' attention would be drawn to him. Yul Brynner became increasingly exasperated by the way McQueen tried to upstage him.

When he was playing tough-guy roles, he didn't convey much in the way of emotional depth. In The Great Escape, for example, his character, "The Cooler King," is defined entirely by his actions. He is an escape artist who sees breaking out of Nazi captivity as his one and only goal.

One of the more surprising aspects of his career, given that he became the best-paid star of his era and is closely associated with action roles, is how effective McQueen was at playing losers and characters on the margins.

Two of his finest and most underrated films, Junior Bonner and Tom Horn, are included in the BFI season.By the time McQueen made Tom Horn (1980), he was already suffering from the cancer that would kill him. That adds extra pathos to a film that is about someone left behind by changing times. His character is a man of the old West: a real-life figure who – the opening intertitles tell us – had ridden shotgun for the stage lines and worked both as a Pinkerton agent and as a cavalry scout "in the bloody Apache wars". He clings to his minor celebrity as the man who caught Geronimo, but by 1901, Horn is all but washed-up.

Production was problematic. Whether through perversity or illness, or because he despised Hollywood and would far rather have been racing bikes, McQueen held the studios to ransom when to appear in other people's films, and invariably demanded complete freedom on his own cherished projects – like this one. His Horn looks old and ravaged. He is, we're told, "a vestige of that heroic era we've just about lost." He moves stiffly, at microscopic speed, his spurs always clinking, but unlike the businessmen, judges and journalists who've colonised the West, he retains a an innocent rapture at the great outdoors. He can't even look at his beloved mountains without a tear coming to his eyes.

This is a film about dying. From the very first sequence, in which Horn drifts into a Wyoming town, shuffles off for his morning whisky and manages to get himself badly beaten up by heavyweight boxer Gentleman Jim Corbett, it's obvious his days are numbered. He knows it, and often seems to be willing his own death. "Committing suicide?", he asks himself. "Is that what I've been doing all these years?" Sam Peckinpah's Junior Bonner is equally moving and well-observed, an elegiac film about a rodeo star whose best days are also behind him and can't cope with the shiny, modern new world.

Given the dignity and pathos of these two performances, it's surprising how seldom he took roles that stretched him. When late in his career, he tackled Ibsen in An Enemy of the People (1978), there was a sense that he was belatedly trying to correct the sense that – as the critic David Thompson put it – "he preferred playing with cars to making movies."

McQueen didn't have great range. He wasn't especially imaginative in the way he plotted his career. "Through all those early blockbuster hits whether it's The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape or The Thomas Crown Affair, he is rather affected," acknowledges Tony Earnshaw. "It's a very distinctive style of acting. A lot of people said he wasn't acting. It was this old humbug about his just playing this version of himself on the screen." What he did have was an effortless charisma.

The idea of "the king of cool" is corny in the extreme. It's a testament to McQueen that nobody ever questions it when this label is pinned to him.

The Steve McQueen season runs at BFI Southbank, London SE1 throughout August (Bfi.org.uk)

IN DEEP: MORE THAN AN ACTION MAN

The Blob (1958)

McQueen brings a surprising conviction and plenty of Method-style intensity to his role to his role as a rebellious teenager pitted against a gooey, amoeba-like monster.

The Thomas Crown Affair (1968)

A rugged action star like McQueen didn't get many chances to play dapper Cary Grant-style romantic leads. This glossy thriller sees him at his most debonair – and famously features an erotically charged chess game with Faye Dunaway.

Papillon (1973)

McQueen goes head-to-head with Dustin Hoffman in this drama about two convicts on Devil's Island. McQueen is laconic and macho while Hoffman is fussy and expressive. Their acting styles are poles apart but complement each other far better than might have been expected.

An Enemy of the People (1977)

McQueen has long hair, a big, bushy beard and horn-rimmed specs in this Ibsen adaptation (above). He plays a crusading doctor trying to save the town from a polluted water system.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments