The Big Question: What is the history of Batman, and why does he still appeal?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

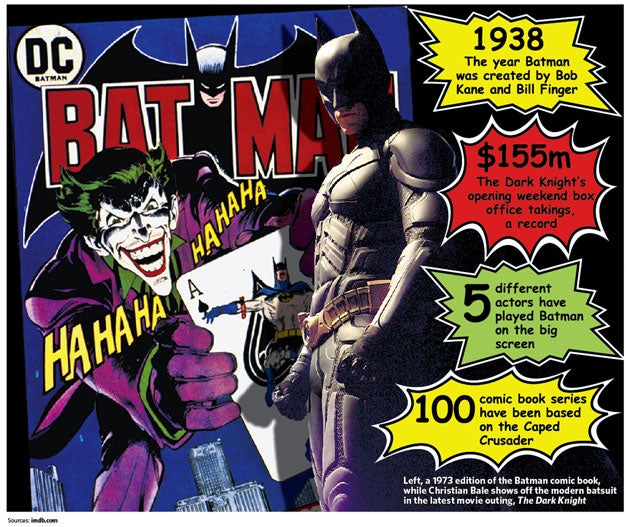

Because the Caped Crusader's latest movie had its British premiere last night – just after news emerged that The Dark Knight had topped the all-time US league for an opening weekend box-office take, with a remarkable $155m, as well as rave reviews about the late Heath Ledger's performance as The Joker. That success snatched the record from another superhero movie, Spider-Man 3.

Where does he come from?

Batman was the brainchild of the artist Bob Kane and the writer Bill Finger, who collaborated on a new character for Detective Comics in 1938. Their first sketches were a long way from the Batman image most people are familiar with today: the first drawings gave him wings and red tights. A few drafts later, a Batman who looked more like the 2008 movie version was born. He was soon starring in his own self-titled comic.

Why was he such a success?

From the start, Batman was unlike other heroes. His rivals, Superman and Spider-Man, are festooned in the primary colours of the American flag, whereas Batman dresses in dark blues and blacks. And no other superhero has a story quite as bleak. When Bruce Wayne was a little boy, he watched his parents' deaths at the hands of Joe Chill, a heartless mugger, and vowed to dedicate the rest of his life to gaining revenge on the criminal underworld. Superman's arrival from another planet is kids' stuff in comparison. To quote the film director and comics geek Kevin Smith: "Batman is about angst; Superman is about hope."

How did he move from comics to the mainstream?

The first big fillip to the Dark Knight's career came in 1966, with the US TV series based on his comic-book adventures. It was a huge success for two years, and the POWs, WHAMs, and Holy Mackerel have an enduring ironic appeal. But the kitsch style, coupled with Adam West's goody-two-shoes performance dealt a near-fatal blow to the the comics, which were sullied for the hardcore aficionados and quickly forgotten by fans of the show. For the next 20 years, the series floundered through numerous relaunches without ever shaking off the high camp reputation of the series. Finally, just as Batman seemed to be on his last legs, Frank Miller wrote the four-issue mini-series The Dark Knight Returns, and changed everything.

Why was Miller's version so important?

As the cultural commentator Jabari Asim put it: "Miller revived what had been a declining character by plumbing his tangled psyche and exposing what he found there." Miller was fascinated by the horrors of the hero's childhood, and bears responsibility for the sense of Batman that most of us have today, as a uniquely downcast hero. That idea's influence on Hollywood, from the Batman series itself to the gloomy thrills of the Bourne movies, can be felt to this day.

What made this Batman different?

In Miller's version, Batman is a 50-year-old who comes out of retirement and has to battle the ravages of time on his body as much as the supervillains terrorising Gotham City. Tim Burton's 1989 Batman drew heavily on Miller's version, giving Michael Keaton's Batman the obsessive, dark personality Miller had imagined. It placed the same emphasis on the fact that, almost uniquely amongst superheroes, Bruce Wayne is not "super" at all, but an ordinary man who sometimes seems more like a vigilante than a hero, and who makes use of high technology, piles of money, his famous wits, and an awful lot of weight training. Critics saw the movie as the first about a superhero to treat the audience like grown-ups: typically, The Washington Post called it a "violent urban fairytale", "an enveloping, walk-in vision".

What happened next?

After a less successful sequel, Burton was dumped by studio executives in search of a more family-friendly director. Sure enough, Joel Schumacher's first effort, Batman Forever, starring Val Kilmer, enjoyed some box-office success; but the next time round, Batman and Robin was widely ridiculed for its garish, overblown style. George Clooney barely survived the mauling. Since then, there's been a renaissance in superhero movies, with Spider-Man and X-Men leading the way – both clearly inspired by Burton's original, darker vision. As a result, Batman himself came roaring back in the form of Christian Bale, in Christopher Nolan's 2005 revival Batman Begins. These days, comic-book movies are everywhere.

Why the box-office surge for superheroes?

It's simple: the audiences keep lapping them up. Hollywood first caught on after the surprise success of X-Men in 2000, and so far the formula hasn't run dry. That's partly the result of the die-hard comic-book fans who routinely see each new title two or three times, and partly because studios can use the fantasy element of the superhero universe to unleash all their most spectacular special effects. There may be more intangible reasons too. According to the comics blogger Josh Flanagan: "This is the kind of movie that can be patriotic and tap into what the United States is craving in a movie right now. That resonates with a lot of people."

So will they continue to be a success?

The Dark Knight's huge success suggests so – but more telling still might be Iron Man, which made $565m and, despite having two big stars, Robert Downey Jr, and Gwyneth Paltrow, was a franchise without anything like Batman's fan-base. If the obscure story of the arms dealer Tony Stark can do so well, the critic Ross Douthat wrote, "the road is cleared for literally dozens of efforts featuring characters just as obscure as Iron Man, if not more so". Tellingly, Marvel, which owns the rights to many of the most popular comic-book heroes (although not Batman himself) has now set up as an independent studio, seeing its future as much in movies as in the comic books it has published since 1939.

What about Batman himself?

His future looks rosy. The success of the new film guarantees a sequel. The current comic book series, Batman RIP, has the fan community in paroxysms of excitement over whether the hero will live or die. But even if he is bumped off, that won't signal his permanent demise. To quote the prominent comics critic Douglas Wolk: "There's no such thing as a 'definitive version' of Batman... there are as many interpretations of Batman as there have been creators who've worked on his stories."

Is Batman the greatest superhero ever?

Yes

*He's often called the World's Greatest Detective, in homage to his formidable deductive intelligence

*His tragic personal history and dark, brooding psychology make him far more interesting than the clean-cut, square-jawed likes of Superman

*He drives the Batmobile

No

*He can't compete with X-ray vision, spider-sense, or super-strength; he can't even fly, only use his cape to glide

*The 1960s TV version will always make him slightly ridiculous

*Lois Lane and Mary-Jane Watson, female foils to Superman and Spiderman, have no equivalent for the Caped Crusader (unless you count Robin, of course)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments