‘We were smoking marijuana for breakfast’: The Beatles and the making of Help!

John Lennon recalled glazed eyes and giggling on Dick Lester’s zany Bond spoof – now recognised as the film that invented pop video, as well as the moment The Beatles’ songwriting left Merseybeat far behind. Mark Beaumont on how a classic was created out of chaos

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

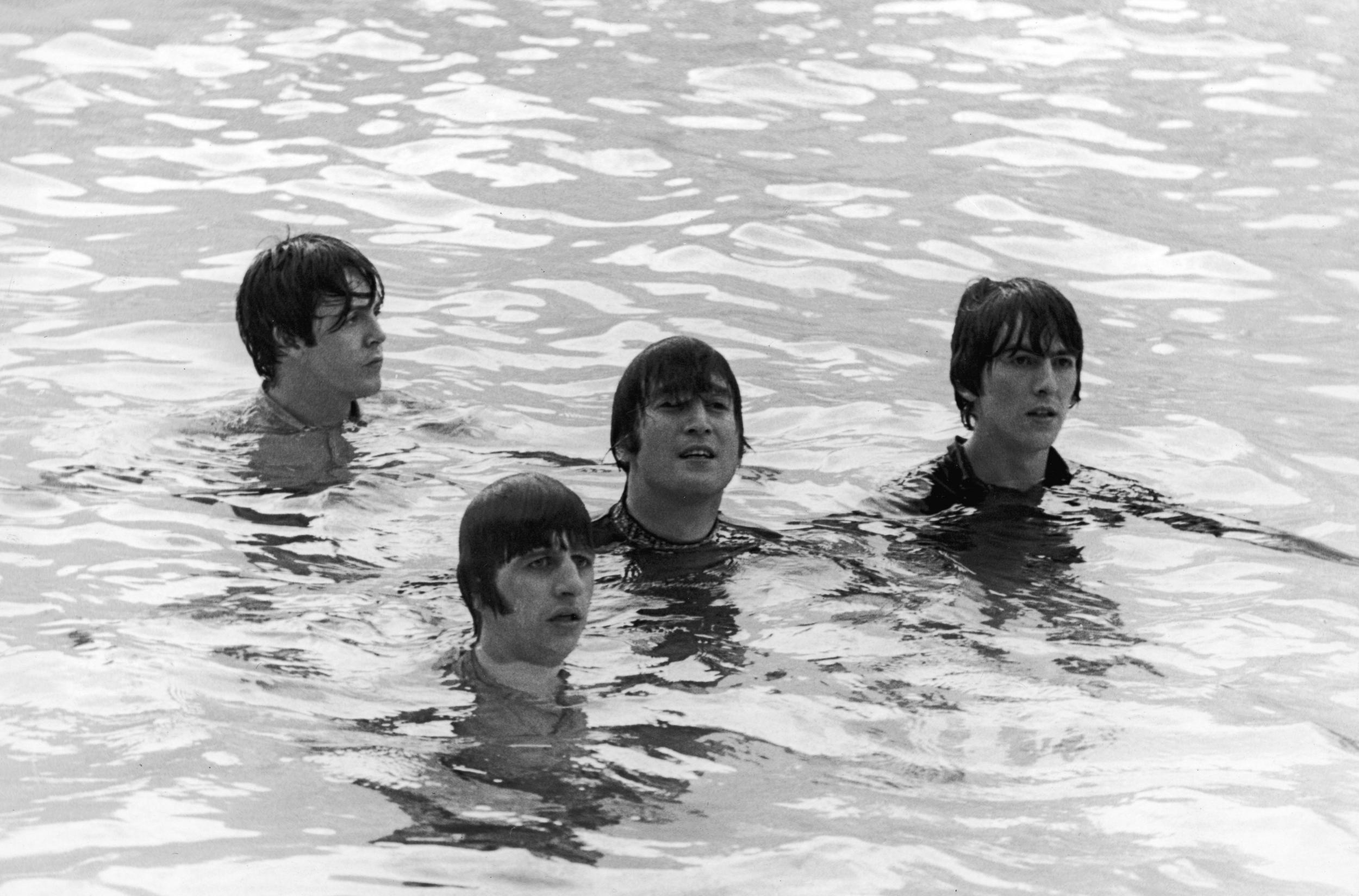

Your support makes all the difference.They smoked pot in the plane all the way to the Bahamas, and jumped in the hotel swimming pool fully clothed. They took over an après-ski party in Austria with a rowdy sing-along and larked about on the slopes barely knowing which way up to hold their poles. They looked for all the world like the ultimate lads on tour; in 2020 they’d probably find themselves the subjects of an Ibiza-based ITV2 reality show, or swiftly deported in handcuffs. In 1965, however, they were merely the biggest pop band in the world, in the middle of the greatest run of musical creativity ever put to tape, letting off celluloid steam.

The Beatles’ second cinematic foray – 1965’s Help!, which began filming 55 years ago today – has long lingered in the shadow of the previous year’s screen debut, A Hard Day’s Night. Though both were directed by Dick Lester, the first film’s documentary conceit and black and white stock lent it an authenticity that perfectly reflected both the Beatlemania phenomenon and the band’s individual characters and wit. It encapsulated a seismic shift in British pop culture; Help!, on the other hand, encapsulated only the cinema trends of the day.

The Beatles claimed the film was inspired by the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, but in practice the flimsy, Tintin-level story of an evil eastern cult hunting down the sacred sacrificial ring which had ended up stuck on Ringo’s finger satirised the technicolour intrigue and exotic plotlines of early Bond to such a ludicrous degree that it almost sat alongside the recent Carry on Spying, and was close kin to Peter Sellers’ 1963 classic The Pink Panther. Indeed, Sellers had been offered an early version of the Help! script, devised by Marc Behm and co-written with Charles Wood, so heavily was it drenched in Goon Show concepts such as abstract interludes and quips delivered direct to camera.

Over time, however, Help! the movie has grown in stature and significance. Not only did the music capture The Beatles at a turning point – a creative second wind after the half-baked Beatles for Sale, the end of their age of innocence, their first surreptitious howl from within the mania, the dawning of a new form of mainstream pop sophistication – but the film’s legendary song segments lay the roots of televised music for decades to come.

The Beatles, signed to a three-film deal with United Artists, had originally looked into making an adaptation of Richard Condon’s sexually charged surrealist western A Talent for Loving as their second movie, but as self-confessed copyists of Goon Show humour they found much to suit them in Help!.

“We didn’t just want The Beatles to make a colour version of A Hard Day’s Night, another fictionalised documentary,” Lester said in 2013. “We couldn’t show them in their private life, which would be the next logical extension to it, because that was by then certainly X-rated ... So they have to become passive recipients of an outside plot or an outside threat brought on by a weakness within themselves… The dialogue was more complex [which] meant they needed a little bit more concentration, and in those days by ‘concentration’ I meant ‘please don’t lose your script in the first week’.”

With a bigger budget at his disposal thanks to the success of A Hard Day’s Night, Lester was able to use colour film stock and explore far-flung locations for a similarly song-spattered film with such suggested titles as Beatles 2, The Day the Clowns Collapsed and, if George had had his way, Who’s Been Sleeping in my Porridge?. The working title was settled on Ringo’s suggestion of Eight Arms to Hold You and the songs put together for the shoot – often landing in Dick Lester’s lap the day before they were due to be filmed – were a significant step on from the hurried Beatles for Sale, which had marked a retreat towards their early reliance on rock’n’roll covers. The dark folk and country tones of that record had matured into a rich melodic seam that bonded The Beatles’ energy with the depths of Dylan. “I had these two guys who used to write songs whenever we needed some,” Harrison joked in a documentary on the film. “I think we just called them up and said, ‘Look, we’ll be doing a movie now lads, could you come up with a couple of catchy hits?’”

A comedy-friendly cast was assembled, including That Was the Week That Was regular Roy Kinnear, acclaimed character actor Leo McKern, Beatles favourite Victor Spinetti and relative unknown Eleanor Bron, fresh from several years embroiled in the New York jazz club scene, as the seductive Ahme. “It was frightening, frankly,” Bron says today. “It was the first feature film I was in. I hadn’t a clue [who The Beatles were]. There was a photograph when we got back of these four people leaping into the air on the King’s Road with strange haircuts.”

With the entire world as their potential film set, shooting began in the Bahamas on 23 February 1965. Legend has it that they filmed in the Caribbean because The Beatles wanted to use the project as an excuse for an exotic round-the-world holiday – in fact, the Bahamas were chosen because the band’s financial advisor, Dr Walter Strach, had set up a tax shelter on the islands, and the band agreed to film there as an act of goodwill.

If the band were expecting a fortnight in paradise when they rolled bleary-eyed off their chartered plane at New Providence Island, they were in for a rude awakening. Shoot days ran from 8.30am to 5.30pm, the islands were chillier than their beach attire costumes suggested, and they found the poverty around them shocking. One location used as a temple in the film was actually a hospital for people with disabilities and elderly. On arrival The Beatles thought it must be a disused army camp and were horrified when they were told its true purpose.

“There was some kind of very crooked administration,” Bron recalls. “It was actually a very horrible experience ... half the island was living in shanties and shacks. We had a big dinner in our honour and the aristocrats, who should have known better, were so rude to The Beatles, it set a very bad example. The Beatles behaved very well [but] they patronised them, dismissed them and were extremely unpleasant.”

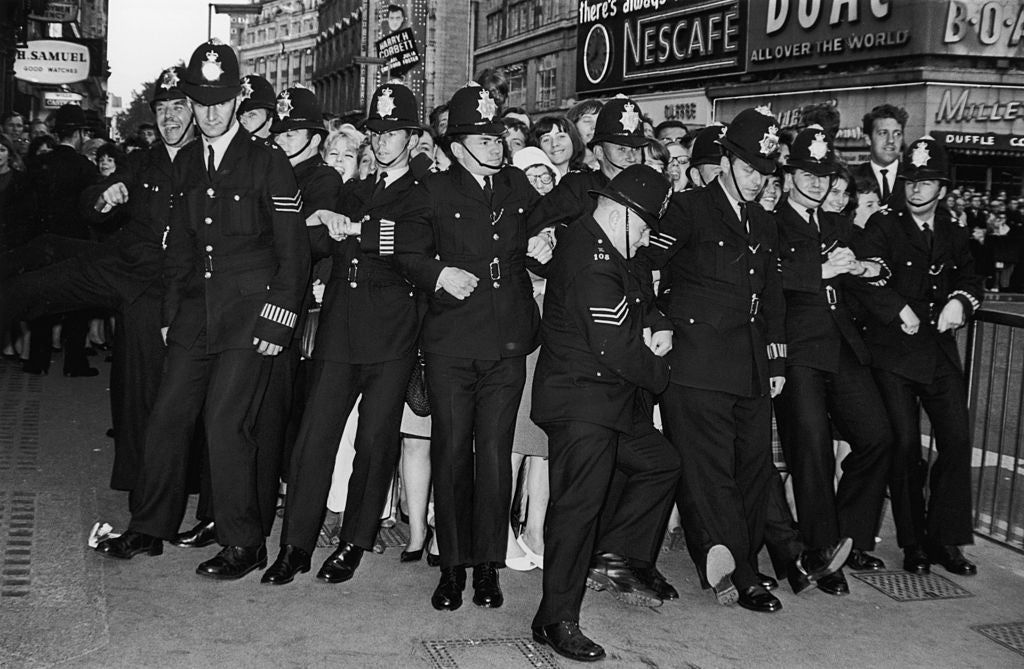

Also, even in this supposedly remote part of the world, Beatlemania caught up with them. After splashing around in the surf of Balmoral Island while filming the sequence for “Another Girl”, a temporary dressing room made of towels was constructed on the beach for them to change their wet clothes, only to be invaded by fans. “Someone would just leap across with a piece of paper saying, ‘Sign this,’” Ringo said later.

Their solution was to make the film in what the band would describe as a “haze of marijuana”. “A Hard Day’s Night I was on pills,” Lennon said in a 1970 Rolling Stone interview. “That’s drugs, that’s bigger drugs than pot ... The only way to survive in Hamburg, to play eight hours a night, was to take pills… Help! was where we turned on to pot and we dropped drink, simple as that. I’ve always needed a drug to survive. The others, too, but I always had more, more pills, more of everything because I’m more crazy probably.”

“If you look at pictures of us you can see a lot of red-eyed shots; they were red from the dope we were smoking,” Ringo said in Anthology. “And these were those clean-cut boys! Dick Lester knew that very little would get done after lunch. In the afternoon we very seldom got past the first line of the script. We had such hysterics that no one could do anything.”

Were the band permanently stoned during filming? “They probably were but I wouldn’t notice,” says Bron. “It’s hard to believe how ill-informed I was about what was going on around me ... John and I were sitting by the ocean and he offered me something and I took a puff and then I thought, ‘This must be terribly expensive,’ and I gave it back.”

Their addled state, and the experience of filming scenes from the end of the movie first, may have contributed to the sense that they were extras in their own film. “The film was out of our control,” Lennon said in 1970. “With A Hard Day’s Night, we had a lot of input, and it was semi-realistic. But with Help!, Dick Lester didn’t tell us what it was all about.” He’d also claim, “it was like being a frog in a movie about clams”, and partly blamed the drug intake. “We were smoking marijuana for breakfast during that period. Nobody could communicate with us, it was all glazed eyes and giggling all the time. In our own world. It’s like doing nothing most of the time, but still having to rise at 7am, so we became bored.”

Yet, as the band frolicked fully clothed in the pool at the Nassau Beach Hotel, shot scenes on schooners and cycled around the island pretending to search for an abducted Ringo, Bron remembers them as a lively, eager-to-learn gang. “They made the most of it,” she says. “They had company, they could be themselves when they were together and boost each other when they needed to be. They were all up for it, whatever it was. They were very keen. I’ve always been incredibly impressed by the fact that they’d done this one film and they wanted to know how to act, they wanted to learn how to do it. You had to look as if you didn’t care but I think they really did care.” How did they handle the early starts? “They probably just didn’t bother going to bed.”

The Beatles returned to the UK on 9 March, before setting off for a week at the film’s second foreign location on 14 March. The small Austrian town of Obertauern was chosen for the ski scenes in order to avoid the larger resorts where more British tourists might recognise them. Filming began on the slopes outside the band’s hotel Edelweiss. “I said to them, ‘Have you ever ski’d?’” Lester said. “None of them had. I said, ‘Don’t try it until we get the cameras out.’ We put three cameras on them and I said, ‘Now learn how to ski, there’s a hill, do it.’ We filmed everything that happened, it all happened for real.”

As the band fooled around on the slopes filming the “Ticket to Ride” sequence, riding snow ploughs and log trains and having riotous picnics, on-set photographer Robert Freeman struck on a concept for the album sleeve while watching them wave their arms around to the music. “I had the idea of semaphore spelling out the letters HELP,” he said. “But when we came to do the shot, the arrangement of the arms with those letters didn’t look good. So we decided to improvise and ended up with the best graphic positioning of the arms.” On the finished sleeve, shot later in Twickenham Film Studios, The Beatles actually spell out the semaphore for NUJV.

In Obertauern, the larks continued. They hosted après-ski parties for the 60-strong crew, played their only ever Austrian concert at the Hotel Marietta to celebrate a crew member’s birthday and continued to make Dick Lester’s life a trial. “In one of the scenes, Victor Spinetti and Roy Kinnear are playing curling, sliding along those big stones,” Ringo said. “One of the stones has a bomb in it and we find out that it’s going to blow up, and have to run away. Well, Paul and I ran about seven miles, we ran and ran, just so we could stop and have a joint before we came back. We could have run all the way to Switzerland.”

You can understand The Beatles’ need to run away from it all. When they returned to Britain to shoot interior scenes at Twickenham Film Studios, where A Hard Day’s Night had been filmed, they were plunged straight back into the chaos. The Beatles For Sale EP, featuring a selection of songs from the album, was making its way towards the top spot, swiftly followed by “Ticket to Ride”. So there were radio interviews and appearances on Thank Your Lucky Stars and Top of the Pops to fit in between days on set, alongside post-shoot evening sessions at Abbey Road to complete “You’re Going to Lose That Girl”, “That Means a Lot” (unreleased until 1996), “Dizzy Miss Lizzy” and “Bad Boy”, and audiences with Bob Dylan, holding court at the Savoy with Allen Ginsberg. Celebrities would show up on set to present them with awards on camera, which the band would sabotage by playing with Simon Dee’s Bell Award or singing “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” in Spanish accents with Peter Sellers, or “Mr Ustinov” as John called him.

At the studios, Beatlemania showed no sign of abating. “They would throw themselves on to the car and everything,” Bron recalls. “That was an early lesson which has stood me in good stead – fame is not the spur, fame has its own way of kicking back.” On a three-day excursion to film Harrison’s “I Need You” on a mock studio set up on a windswept Salisbury Plain surrounded by tanks lent by the 3rd Division, Royal Artillery, fans broke into their Austin Princess limousine parked back at the Antrobus Arms hotel and stole any clothes, cigarette butts and souvenirs they could find.

Considering the surreal fill-in scenes they were shooting at Twickenham, it’s no wonder an already drug- and fame-muddled Beatles felt even more confused by the whole escapade. One day they might be fending off a Bengal tiger in a pub basement, the next they could be chased by a gang of bagpipers, have their shirts pulled off by overactive hand dryers, get shrunk to microscopic size or fight off eastern assassins hiding inside letterboxes. “I’m not sure anyone knew the script,” Paul said in Anthology. “I think we used to learn it on the way to the set.“

Hence, when John came to write the title track for a movie now called Help!, his relief at not having to pen a song called “Who’s Been Sleeping in my Porridge?” was tempered by an authentic desperation.

“When ‘Help!’ came out in ’65, I was actually crying out for help,” he told Rolling Stone of a song recorded in just four hours on 13 April. “It was my fat Elvis period ... I may be very positive – yes, yes – but I also go through deep depressions where I would like to jump out the window, you know. It becomes easier to deal with as I get older; I don’t know whether you learn control or, when you grow up, you calm down a little. Anyway, I was fat and depressed and I was crying out for help… I meant it – it’s real.”

If “Help!” marked a distinct step towards the darker personal themes the band’s music would soon explore in depth, on set another culture-defining musical revelation occurred. While filming interior scenes for the Rajahama Indian restaurant at Twickenham on 5 April, Harrison became fascinated by the sounds of the Indian instruments brought in for musicians to play in the background.

“I remember picking up the sitar and trying to hold it and thinking, ‘This is a funny sound,’” Harrison told Billboard in 1992. “It was an incidental thing, but somewhere down the line I began to hear Ravi Shankar’s name. The third time I heard it, I thought, ‘This is an odd coincidence.’ I went and bought a Ravi record; I put it on and it hit a certain spot in me that I can’t explain, but it seemed very familiar to me … my intellect didn’t know what was going on and yet this other part of me identified with it. It just called on me.”

“The first time that we were aware of anything Indian was when we were making Help!,” Lennon said in 1972, recalling an additional Indian influence the band had encountered in the Bahamas. “A little yogi runs over to us ... and gives us a book each, signed to us, on yoga. We didn’t look at it, we just stuck it along with all the other things people would give us. Then, about two years later, George had started getting into hatha yoga. He’d got involved in Indian music from looking at the instruments in the set. All from that crazy movie. Years later he met this yogi who gave us each that book.”

The Beatles completed Help! in the same jocular spirits they began. On a two-day shoot in early May at the sumptuous Cliveden House – the stately home at the centre of the Profumo affair – in Maidenhead being used as a stand-in for Buckingham Palace, they won a relay race around the gardens against three crew teams and struggled to keep straight faces on camera. “I remember one time at Cliveden we were filming the Buckingham Palace scene where we were all supposed to have our hands up,” McCartney said in Anthology. “It was after lunch, which was fatal because someone might have brought out a glass of wine as well. We were all a bit merry and all had our backs to the camera and the giggles set in. All we had to do was turn around and look amazed, or something. But every time we’d turn round to the camera there were tears streaming down our faces.”

When they watched the finished film back with clearer heads ahead of its July 1965 release, they were sobered by it, and disappointed too. In terms of cultural significance, it cowered in the shadow of its own soundtrack, where “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away” was merciless in its Dylan-esque introspection (and arguably tackling the then-taboo topic of Brian Epstein’s homosexuality), the title track defined and conquered the Merseybeat explosion and “Yesterday” was set on course to become one of the most covered songs this side of “Happy Birthday”. Help!, the album, was the point where The Beatles ascended to a sonic sphere far elevated from mere pop music – Lennon would even claim that “Ticket to Ride” was one of the earliest heavy metal songs.

Bron recalls sensing the magic in the air when she sat on a sofa in The Beatles’ stage-set communal house with four separate front doors, being serenaded by “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away” and fielding suggestive winks from McCartney. “It was simply wonderful,” she says, “I was used to standards and the hit parade, so it was a strange juxtaposition because it was all change.”

Gradually, though, the film’s influence grew, too. “I realise, looking back, how advanced it was,” Lennon would admit. “It was a precursor to the Batman ‘Pow! Wow!’ on TV – that kind of stuff.” But even this sells it short. Its effervescent musical interludes and surreal humour became the blueprint for The Monkees, and would go on to inspire Monty Python, the Airplane! diaspora, and even Spike Lee, who bought every available format of the film. And Lester’s experimental use of reflected light, hand-crafted colour filters, mirrored angles and shooting through objects such as film reels set the visual tone for a million copycat music videos to come.

“I was sent a parchment scroll from MTV declaring that I was the father of MTV,” Lester later recalled. “I immediately cabled back and demanded a blood test.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments