Netflix’s Ted Bundy documentary and the problem with peak true crime

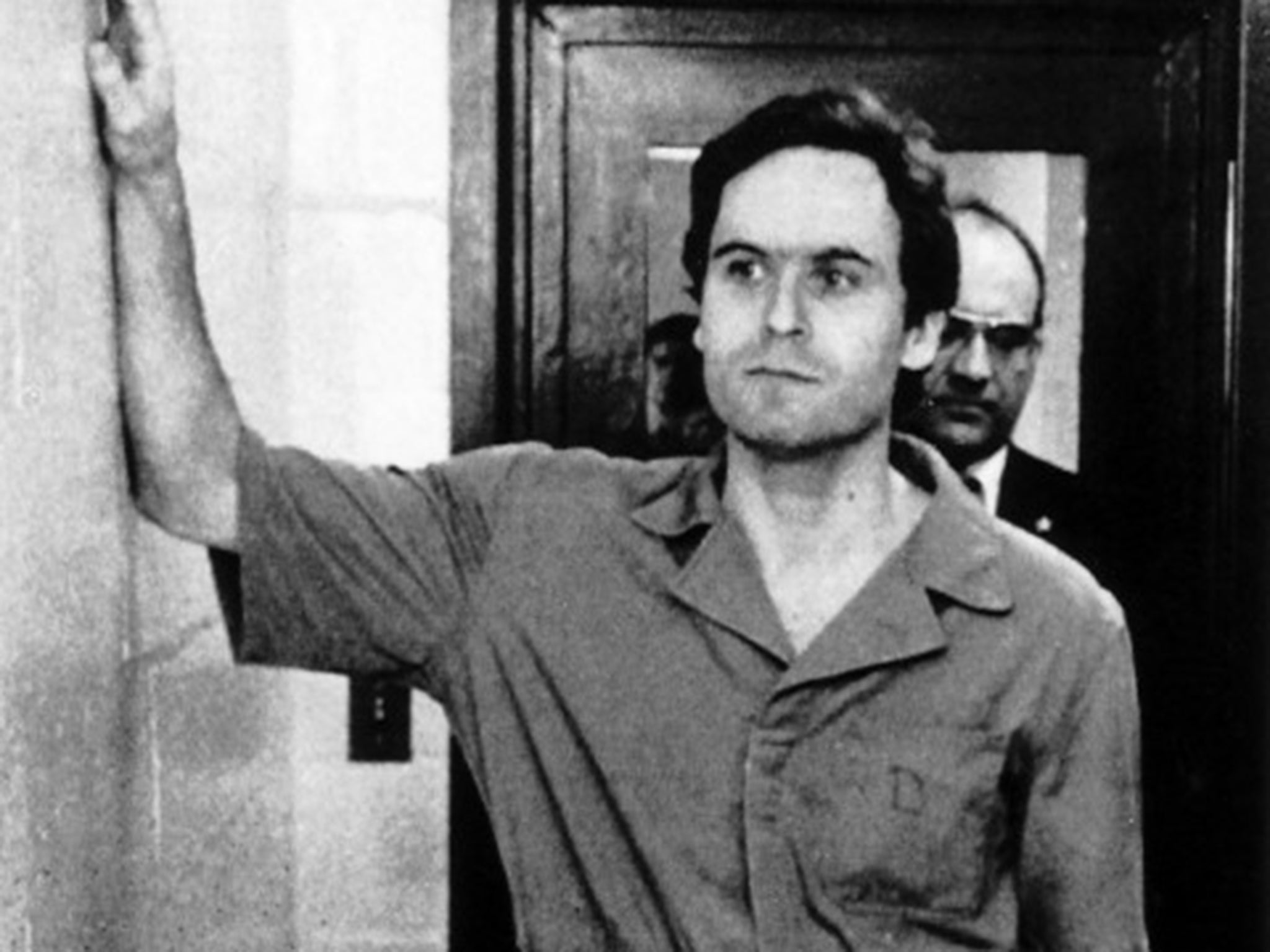

Bundy is the David Brent of serial killers – obviously evil and deranged but also obsessed with the limelight, writes Ed Power. Is it moral to now restore to him his voice?

The true crime genre has been approaching its saturation point for some time now, and Netflix’s bloated new documentary about serial killer Ted Bundy could mark a point of final overload. It isn’t just that Conversations with a Killer: the Ted Bundy Tapes is simultaneously exploitative and underwhelming, crass and listless. What’s more striking is how thoroughly un-creepy this psychoanalysis of the notoriously “charming” murderer feels. It’s ludicrous that Netflix felt the need to warn subscribers not to watch it alone (unless they were joking – but who jokes about serial killers?).

All of that is despite director Joe Berlinger’s best efforts to play up the ghoulish contrast between Bundy’s superficial likability and his murder of 30 women through the Seventies in the Pacific northwest and later Florida (the final tally of his victims may be even higher).

“I am looking for an opportunity to tell the story as best I can,” says Bundy in one of the recorded interviews that are the doc’s unique selling point. “I’m just a normal individual.”

Yet Bundy comes across less as a wolf among sheep than as a violent weirdo, in the end a mystery only to himself. The problem is that there’s no puzzle to untangle – nothing to chew on for audiences that have already gorged on the intricate grisliness of Making a Murderer, Amanda Knox, The Staircase, The Innocent Man, etc.

Bundy’s crimes – decades old and in most cases long solved – feel, by contrast, like a cross-word puzzle with all the answers already filled in. The live wire tingle of suspecting another twist around the corner is absent.

Conversations with a Killer also promises more than it can deliver. The lure is the opportunity to hear the voice of a monster on tape. Portrayed in popular culture as a real life Hannibal Lecter – clever, dashing and feral – Bundy would, it was hinted, be deconstructed via more than 100 hours of interviews conducted with him by journalists Stephen G Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth in the Eighties.

What Netflix doesn’t tell you – and which Berlinger takes a very long time revealing – is that Bundy imparts little of substance on the tapes. He’s a dreary narcissist, delighted to have reporters hanging on his words. But he protests his innocence and refuses to delve into his crimes. It’s all about him – not his victims.

The closest Bundy comes to pulling back the veil is when Michaud asks him to hypothesise as to what sort of person would have committed the gruesome murders of which he is accused. Even here he has little substantive to impart.

“How do you describe going to the mouth of any great river and pull out a handful of water,” he says, explaining that a killer’s motivations likely extended to their childhood. “We’re talking microscopic events.”

He went to the electric chair in January 1989 (the new series coincides with the 30th anniversary of his death). On that day, in a park across from Florida State Prison, hundreds gathered to celebrate his demise. They danced, set off fireworks and then broke into cheers as a hearse carrying Bundy’s coffin emerged through the gates. Is it moral to now restore to him his voice, even if he chooses to use it mostly to drone on about his popularity at high school?

The portrait painted is of the David Brent serial killers – obviously evil and deranged but also obsessed with the limelight and entirely unaware of the ludicrous figure he cuts as he insists on defending himself at trial.

Yet it’s unclear whether Berlinger understands how much of a black hole his protagonist is. The makers of Conversations with a Killer seem almost hypnotised by Bundy. That’s another flaw with “Peak True Crime”: the insistence that we, too, are bedazzled by their subjects (see also Michael Peterson in The Staircase, Marjorie Diehl in Evil Genius etc).

There is also the problem that all of these true crime shows are starting to flow into one another. Each arrives with an interchangeable David Fincher’s Seven-meets-True Detective title sequence.

And all cleave to the same tempo. Grainy footage from a pastoral American idyll is interspersed with talking head eyewitnesses. Typically there will be a central protagonist – it helps if they are enigmatic, with just a hint of menace – protesting their innocence. Unearth a dogged cop/reporter/defence lawyer pursuing the truth all these decades and so much the better.

Perhaps that is ultimately why the Ted Bundy Tapes feels as if it’s tumbled off a production line. There’s so much true crime on television that not even a smiling serial killer who murdered at least 30 women can hope to stand out.

Watching Conversations with a Killer, you’ll find it hard not to conclude that the documentary-making community should itself be in the dock. It’s grown fat foisting these identikit repackagings of other people’s tragedies onto us as parlour entertainments. Maybe it’s time to stop dining out on gore and misery.

Conversations with a Killer: the Ted Bundy Tapes is available on Netflix

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks