Studio Ghibli is back. But Hayao Miyazaki's former colleagues are busy taking anime in new directions

When Hayao Miyazaki retired in 2013, animators from Japan's beloved Studio Ghibli set up their own studios. Then Miyazaki came back out of retirement... Robert Ito looks at what may happen next

What happens when the creative heart and soul of a studio retires? If it’s Hayao Miyazaki, the studio shuts with him, it seems.

Not long after the legendary anime director, now 78, announced in 2013 that he was calling it quits (not his first time), his movie home, Studio Ghibli, halted production, ending its three-decade run with two Oscar-nominated films, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya and When Marnie Was There. The news left animation fans across the globe wondering if the makers of such beloved films as Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away would ever release another feature.

The decision also raised other questions. Could Miyazaki – one of the world’s most ambitious and tireless directors – actually stay retired? And what would all those other creative minds at the studio do?

For Ghibli producer Yoshiaki Nishimura (The Tale of Princess Kaguya) the answer was simple, at least in theory. He would create his own studio, pulling some of the top talent from Ghibli’s deep stable of feature film animators.

The result is Studio Ponoc, which began life in 2015 in Kichijoji, a neighbourhood in western Tokyo that’s home to the Ghibli Museum and a major centre for Japanese animation. Despite a tough start – low budgets and a reported staff of “two to three” – Ponoc quickly expanded its workforce to more than 400.

The studio’s first feature, Mary and the Witch’s Flower, was a hit, becoming one of Japan’s biggest box-office draws in 2017. Its second, Modest Heroes, was released in the United States on Thursday.

The transition looked pretty seamless until Miyazaki announced in 2017 that – surprise! – he was coming out of retirement to direct one more feature. Theories abounded: he wanted to create one more film for his grandson (the Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki’s explanation). Or the master was lured back by the sweet promises of computer animation (as revealed in the 2016 documentary Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki). Or he got tired of hearing up-and-coming animators dubbed the “new Miyazaki”.

“Honestly, I think Miyazaki isn’t Miyazaki unless he’s creating something,” Susan Napier, author of Anime: From Akira to Princess Mononoke and Miyazakiworld: A Life in Art, says. She adds: “That’s where he is alive. He loves to create and imagine.”

What looked like an ending became something else – the continuing tale of two studios, one rising and going unexpected places, one resurrected and returning to its focus on a revered filmmaker, all set against the backdrop of a Japanese animation industry thriving as never before. (The 2016 box-office smash Your Name brought in $350m [£270m] to become the highest-grossing anime feature of all time.)

If Ponoc’s first movie, Mary and the Witch’s Flower, had elements in common with a previous Ghibli classic, 1989’s Kiki’s Delivery Service (the young female witch protagonist, the black cat familiar, the broom-borne aerobatics), its second, Modest Heroes, is something else entirely. First, it’s not a feature at all, but a collection of shorts, a format that Ghibli would never release in commercial theatres. If you want to see, say, Mr. Dough and the Egg Princess or Water Spider Monmon, there’s only one theatre in the world where you can see them.

“Studio Ghibli does create short films for exhibition at the Ghibli Museum,” Nishimura says. “But these are all designed and planned by director Hayao Miyazaki. Other creators are not able to realise their plans.”

With Modest Heroes, some of those same artists are making shorts meant to be seen outside of a museum setting, and directing their own works for the first time.

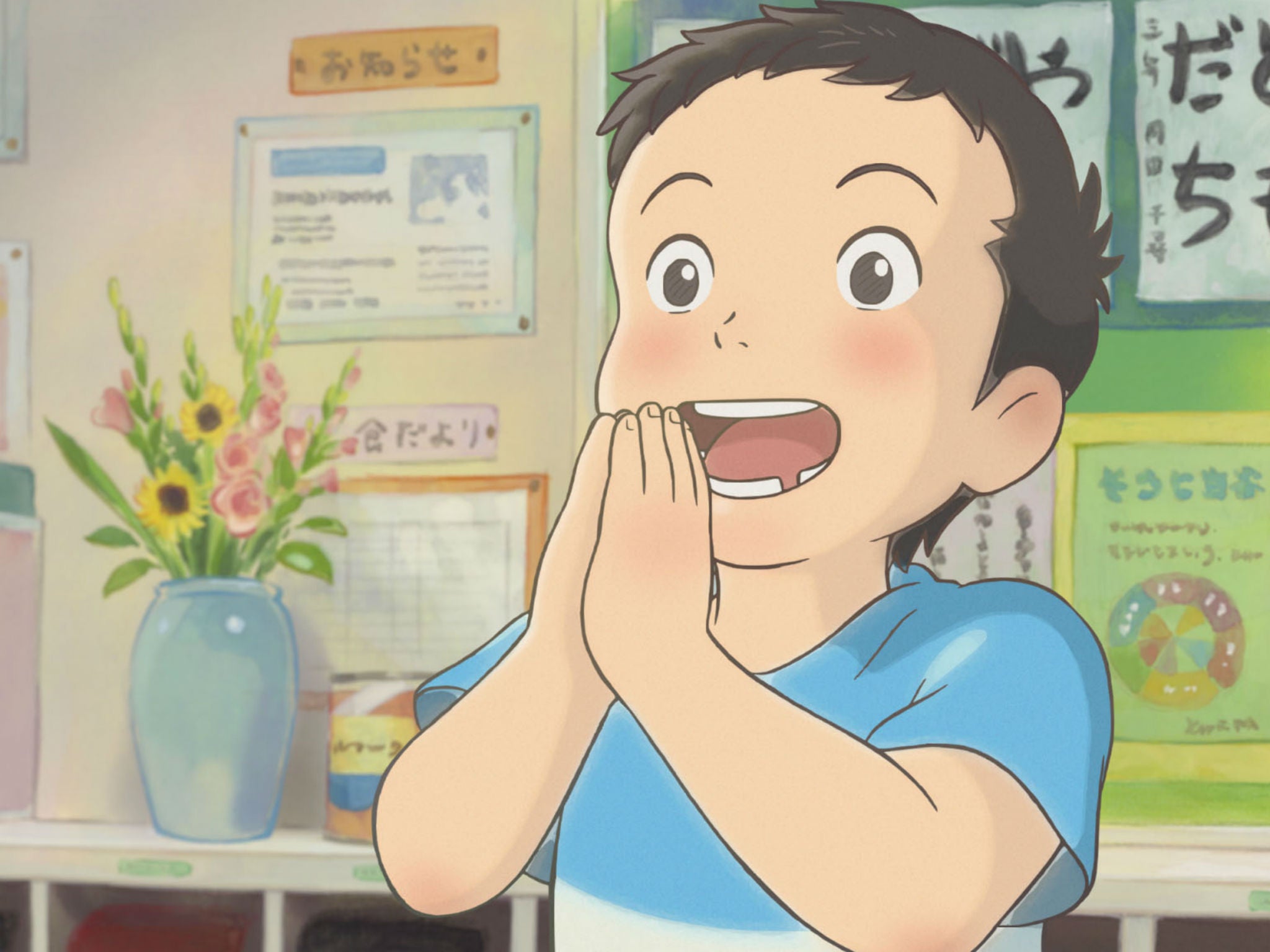

In Kanini & Kanino, Academy Award-nominated director Hiromasa Yonebayashi (The Secret World of Arrietty) tells the story of two crab brothers who encounter menacing minnows and stampeding raccoons (the crab boys are very, very small) on a quest to save their dad. In Life Ain’t Gonna Lose, animator and first-time director Yoshiyuki Momose (Spirited Away) finds high drama in a young boy’s life-threatening food allergy (fried eggs and squeeze-bottle mayo have never looked so fearsome).

The Ponoc films are a major departure from two of Ghibli’s most recent works: The Wind Rises ended with the hero losing his young wife to tuberculosis; and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya with the heroine leaving her earth-born parents to return to her home on the moon.

“Many of the stories we created at Studio Ghibli as the studio was winding down were about separation,” Yonebayashi, the director, says. “But as we started production anew at our new studio, we turned away from stories of separation to stories about coexistence and encounters.”

Modest Heroes was initially envisioned as four films, with director and Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata contributing a seven-minute segment based on a story from the Japanese epic Heike Monogatari. But that project was cancelled when Takahata died in 2018 at 82. Nishimura worked with the director during the last ten years of his life, and says he was inspired to join Ghibli after seeing Takahata’s critically acclaimed Grave of the Fireflies as a young boy. “When Isao Takahata died, I cried like I have never cried before, and I felt like a part of me had been chipped off from the shock,” he says. Modest Heroes ends with a dedication to him.

Studio Ponoc is in the midst of planning another short film and several feature-length ones; Studio Ghibli’s next film, How Do You Live?, based on a 1937 fantasy novel by Genzaburo Yoshino, is slated to open in 2020 or 2021.

The current boom in Japanese animation has led to a shortage of capable animators, a major issue in an industry notorious for its often breakneck work schedules. “Some people I met who had worked with Miyazaki on Princess Mononoke are still traumatized by it,” Napier says. “Miyazaki himself acknowledged it. He used the term ‘boro boro,’ which means ‘crumbling.’ They really rode people to the limit there.”

Ponoc felt the pressure early on. “There was always a group of talented staff members on ‘standby’ from the beginning of production of director Hayao Miyazaki’s films at Studio Ghibli,” Yonebayashi says. “With Mary, we had to start from scratch, with no one.”

In addition to releasing both of Ponoc’s films in the United States, the distributor GKIDS also holds the North American theatrical rights to Studio Ghibli’s classics (rights acquired from Disney in 2011). If the stars align, GKIDS could release a Ponoc film and Miyazaki’s latest “last” film at the same time. “Of course we would love to get” the Miyazaki film, the GKIDS president, Dave Jesteadt, says. “That would be a huge honour. But separate from the business side, I’m just very excited to see it, just like any other fan.”

And the prospect of Ghibli and Ponoc making films at the same time? “It was unexpected,” Jesteadt says. “Although maybe not so much in hindsight. There have been multiple times that Miyazaki has retired and unretired. But I think that while there’s great fellowship and a lot of shared animators and talent between those studios, it’s also great for both companies to have a little artistic competition. There’s always room for more great films.”

© 2019 The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks