Strikes... camera, action

From 'I'm All Right Jack' to 'Made in Dagenham', cinema has found rich pickings in industrial turmoil.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Strikes are back on screen. It is surely no coincidence that at a time when RMT union leader Bob Crow is calling for a campaign of civil disobedience against spending cuts in the UK and public- sector workers from Greece to South Africa and France are taking industrial action, film-makers are also heeding the call to arms.

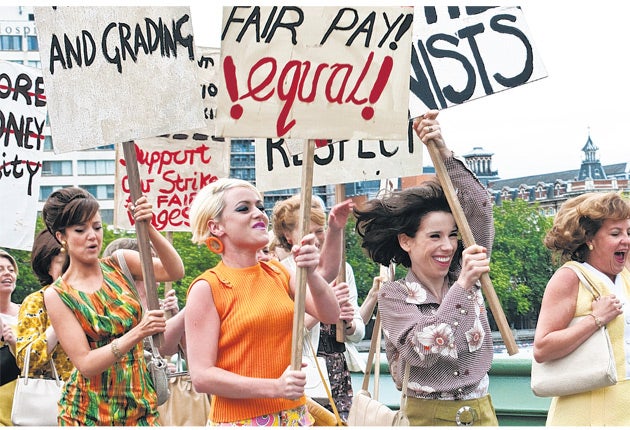

Next month sees the release of Nigel Cole's Full Monty-style yarn Made in Dagenham, about women workers in late 1960s Dagenham coming out on strike against sexual discrimination in the workplace. Last week in Venice saw the world premiere of François Ozon's deliriously funny 1970s-set Potiche, a comedy set against the backdrop of a provincial French umbrella factory. The workers, led by union boss Gérard Depardieu, are forever downing tools in the face of abusive behaviour from their bourgeois bosses.

What is surprising about such films is the nostalgia they show for an era which (in the Thatcher and Blair years at least) was regarded with open disdain. Strikes belonged to the troglodyte past. The images of NUM leader Arthur Scargill at picket lines in Yorkshire or Lech Walesa leading the Polish ship workers in Gdansk seemed to belong to another age. Until recently, film-makers didn't appear interested in revisiting that age or in making movies that dealt with industrial strife.

There have been films made about strikes from the silent era onward. These have come in every shape and invariably reflect the political prejudices of their directors and producers. They combine tragedy and comedy by turns. Some have been paeans of praise to heroic workers. Others have been sneering satires about lazy, self-interested union leaders. There have been self-reflexive, essayistic movies analysing labour relations and melodramas about families struggling to cope when no one is bringing home the wages.

Arguably, the grandfather of the genre was Sergei Eisenstein's debut feature, Strike (1924), heralded by the Soviet press as "the first revolutionary creation of our cinema." This is unashamedly a propaganda piece. Deceitful, corpulent capitalists and brutal soldiers are shown betraying and terrorising the workers. There are intertitles quoting Lenin. As rousing as the political message is the dynamic editing, Eisenstein's marshalling of huge crowds of extras and his telling use of close-ups. He has an eye for the incongruous image (for example, the tiny children playing with cats as sheer chaos rages around them). He is also prepared to be very brutal in what he depicts – for example, a soldier throwing a baby to its death. The shots of a cow being slaughtered are juxtaposed none too subtly with images of fallen workers massacred by the Czar's army.

From Gracie Fields films in the 1930s to Billy Elliot (2000), British cinema has often somehow found humour and pathos in films about workers pitted against bosses. Fields' character in films like Sing As We Go (1934) and Shipyard Sally (1939) was like a shop steward and a favourite aunt rolled into one. In the final scene of Sing As We Go, she is shown leading a crowd of unemployed, Union Jack-waving workers back to the mill from which they were laid off. "Jobs Again!" trumpet the papers as she leads her unlikely march of smiling followers back to a promise of full employment. In Shipyard Sally, she is like Jimmy Reid in a pinafore as she enjoins the Clydeside shipbuilders to head to London and demand their jobs back: "Why, you boys are the greatest shipbuilders in the world! Britain owes you a lot and you ought to remind her of it. If I was in your shoes, I'd go up to London to see this Lord Randall, let him know how bad conditions are and demand work!"

The naive optimism of the Gracie Fields films is in stark contrast to the far more cynical attitude toward workers and strikes found in some British films of the 1950s. John and Roy Boulting, who had made idealistic, socially conscious films like Thunder Rock (1942) had become more pessimistic by the following decade when they made I'm All Right Jack (1959). The film is very funny indeed but has an entirely jaundiced vision of trade-union leaders. Peter Sellers gives one of his greatest performances as Fred Kite, the union leader who speaks in tongue-twisting jargon. "We do not and cannot accept the principle that incompetence justifies dismissal. That is victimisation!" Kite declares as he rallies his men to save the job of upper-class nincompoop Ian Carmichael. Kite may be able to keep the picket line solid, but he is helpless to control the actions of his own wife or daughter who end up going on strike against him.

There is a similar animus against unions in Guy Green's The Angry Silence (1960). The film is about a factory worker (Richard Attenborough) who is victimised when he refuses to take part in an unofficial strike. After crossing the picket line, he is victimised by his colleagues. Like Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront, he is portrayed by the film-makers as the heroic individual standing up against the mob.

Even more sneering toward unions and strikes (which are seen as part of "the British disease") is found in Carry on at Your Convenience (1971), about the rumblings of industrial discontent at lavatory factory WC Boggs & Son. This is a company at which the union leader Vic Spanner (Kenneth Cope) calls strikes almost at a whim, over the most inconsequential incidents.

At around the time the Carry On crew was mocking the British habit of calling strikes at random, over in France Jean-Luc Godard and his collaborator Jean-Pierre Gorin were making Tout Va Bien (1972). This was about a strike at a sausage factory. Keen to lay bare the means of production, Godard opens the film with a shot of cheques being written. "If you use stars, people will give you money," a voice-over tells us. Godard has one of the biggest American stars of the time in tow – Jane Fonda. She plays an American journalist. Yves Montand is a film director who has lost his way. These two big names clearly helped get the film financed, but there is little about the movie that is remotely conventional. Characters talk directly to camera. There are reflections on Marxism and the class system. Godard relishes the collision between agit-prop and mainstream commercial film-making. Audiences, though, were baffled.

Strikes have also provided the subject matter for historical period epics. Claude Berri's Germinal (1993), adapted from the novel by Émile Zola about striking coal miners, was a film on a self-consciously grandiose scale. Set in a 19th-century French mining town, it contrasted the lives of the impoverished workers living in squalor with the carefree lives of the bourgeois mine owners. There is one very telling scene in which we see the enormous mud-encrusted miner Gérard Depardieu taking a bath. Berri goes out of his way to make him look like a creature who has emerged from the bowels of the earth.

There are obvious reasons why relatively few Hollywood films have been made about strikes. During the heyday of the the studios, studio bosses weren't especially well-disposed toward unions. The animator Art Babbitt (who created Goofy) was fired from Disney in 1941 for his union activities. This, in turn, helped provoke the Disney animators' strike of that year – an incident which helped cloud Disney's folksy, all-American image for good.

Contemporary Hollywood is heavily unionised. The writers' strike of 2007-2008 caused huge upheaval in film and TV production, but wasn't in itself a subject that anybody had a desire to make a movie about.

The British miners' strike of 1984-1985 was such a convulsive moment in recent British social history that it continues to be turned to by film-makers. Billy Elliot was set against the backcloth of the strike. In 2001, film-maker Mike Figgis filmed a re-enactment of one of the strike's most violent incidents, the Battle of Orgreave. The miners' strike apart, film-makers have shown little recent enthusiasm for making movies about strikes or confrontations between workers and bosses and politicians. However, as films from Made in Dagenham to Potiche attest, at a time of economic turmoil, dramas about injustice in the workplace have a new-found resonance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments