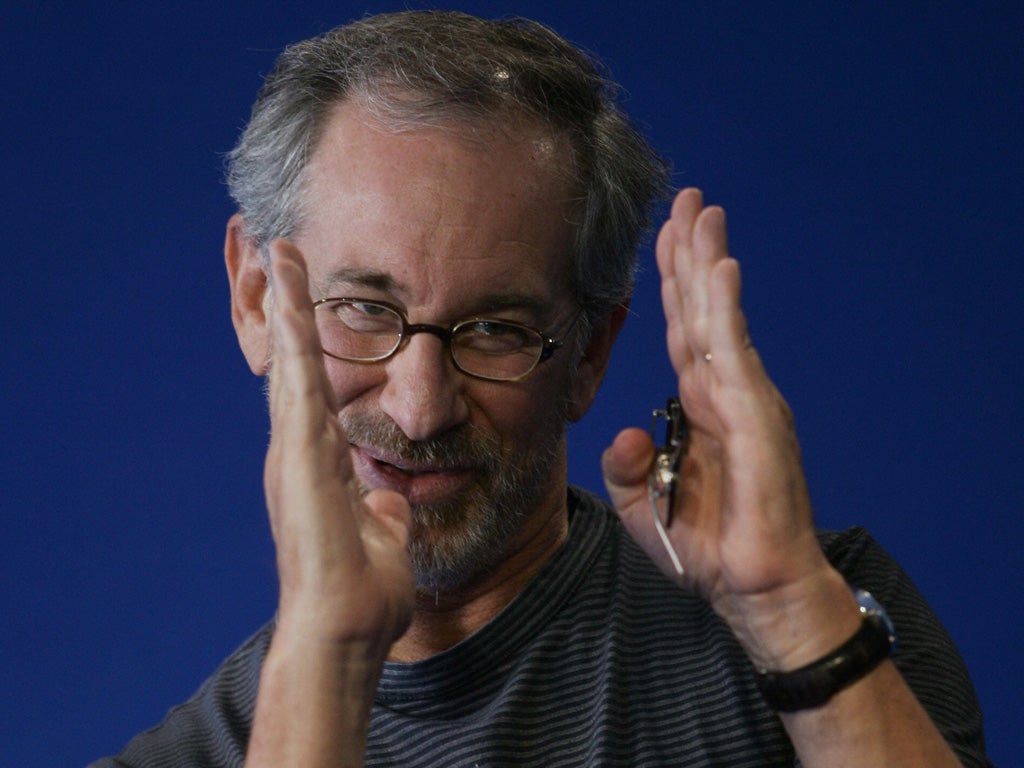

Steven Spielberg: 'I grew up with stories about war'

As his new film opens, Steven Spielberg explains how much his career is influenced by his war veteran father, and reveals his next projects

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Steven Spielberg is talking about the best piece of advice he ever got. It came from François Truffaut, the nouvelle vague director Spielberg cast in his 1977 sci-fi classic Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He'd seen him perform in his own 1970 film, The Wild Child, and wrote the role of the French government scientist with him in mind. "He even called me a 'wild child'," he says, a smile stretching across his instantly recognisable bespectacled face. "He told me, 'You're a kid. You must work with children. I loved the experience myself. I'd recommend it to you. You must go off and make a movie with kids.' And I never forgot that advice."

Speaking to the world's inner child, whether it's in films like E.T, Hook or Empire of the Sun, arguably accounts for why Spielberg, 35 years on from that close encounter, remains the most successful Hollywood director of all time. Detractors say he has infantilized cinema, he simply responds that he's being true to himself. "You can't intellectually purge yourself of who you are. Whatever that is, it's going to come out in the wash, the film wash. What you are is going to be relevant, if not to yourself, to the movies you make. If I'm still making movies that have that sense of childhood, it's because I haven't ever drifted too far away from that source."

Today, he is holed up in L'Hôtel Le Bristol in Paris, the latest pit stop in a European tour to promote new film, War Horse, his syrupy-but-stirring adaptation of the Michael Morpurgo novel. Despite the appearance of a flat-cap (replacing his trademark baseball one), he hardly seems like a man who turned 65 last month. But then film-making is the elixir that keeps him young – or at least reminds him of the buzz he got making 8mm shorts as a child in New Jersey. "If there's a secret or any kind of explanation for why I have been doing this for as long I've done it, it's that when I make a movie today, I have the same feeling – the same nervous energy, that same giddiness, that same excitement."

Lately, he's been even giddier than usual, with the release of the long-in-the-works Tintin coinciding with post-production on War Horse and the shoot for his next, Lincoln, the 27th theatrical feature film of his remarkable 40-year career, which he finished just four days before Christmas. "When I don't have a story to tell, I'm a terror to live with," he admits. "Ask my wife [Kate Capshaw, to whom he's been married now for 20 years] and my children what it's like to have me without a movie in my immediate future to direct. I mope. I walk around the house in a terrible state. I'm miserable when I don't have something that I can immediately jump into."

It recalls the time when, in a 12-month period between 1996 and 1997, he completed the shoots of Jurassic Park sequel, The Lost World, slavery epic Amistad and the Second World War saga Saving Private Ryan. "Everybody said, 'How can you possibly do that?' And I'd say, 'Read up on your history of Hollywood. John Ford directed four movies in a year. Howard Hawks and Raoul Walsh the same.' That was what the business used to be like." In the past he's called himself "a blue-collar director", referring to himself as a "working stiff". The head of DreamWorks studio clearly wants to be remembered as much for productivity as he does artistry.

Certainly, War Horse is an old-fashioned throwback to the films of Ford, from The Quiet Man to How Green Was My Valley, with its lingering shots of the Devon countryside an almost too-simplistic contrast to the bloody realities of the Battle of the Somme, where the story ends up. It was Spielberg's long-time friend and producer Kathy Kennedy who recommended both the book and the resulting West End play, claiming it was in his "wheelhouse". So entranced was he, War Horse took just seven months from the moment he commissioned the script to the first time he called "action" – a personal record it shares with E.T.

Spielberg reports that his youngest daughter Destry, 15, a horse enthusiast and a competitive rider, begged him to make War Horse for her. She needn't have worried, for this story of Joey, a courageous farm horse who gets swept up in the Great War and touches the lives of those he encounters, is like celluloid catnip to him. For this father-of-seven, "the family values, the salt-of-the-earth values, made this film something I couldn't resist," he admits. Throw in the backdrop of the First World War, and the director who has so often returned to the Second World War (from his disastrous comedy 1941 to his TV series Band of Brothers and The Pacific) must've been drooling.

If anything draws him to war stories, it's his father, Arnold, an electrical engineer who fought in the Second World War and turns 95 this year. He regaled the young Spielberg with stories of his time in Burma fighting the Japanese, inspiring many of his son's early 8mm shorts. "He never did it because he was trying to teach me something," he says. "It was just his life. I was born a year after the war ended. And all of his friends were veterans, from then Second World War. They used to hang out together in years and years, so I grew up with these stories. I don't think we ever talked about the First World War. But that's the great thing about making movies and telling stories. History opens up new worlds to film-makers all the time."

Look deeper, and you can see that Spielberg, like so many sons, has always sought his father's approval, which may account for why films from E.T. to Empire of the Sun feature a boy with an absent father figure. Even the jokey relationship between Indiana Jones and his patriarch suggests a need to be accepted. And in War Horse, Albert (Jeremy Irvine), the boy who raises Joey and then resolves to find him when they are separated at the outbreak of war, experiences friction with his drunken father (played by Peter Mullan).

If this need for fatherly acceptance drove him towards movie-making, beginning with 1971's TV movie, Duel, before his career exploded with Jaws four years later, it was almost to the detriment of all else. "I thought film was more important than life itself for many years," he says. "But I was naive to the world until my first child was born in 1985." He's referring to Max, his only child from his first marriage to actress Amy Irving. "Then I was able to be actually be more truthful in my movies because I had a real human being in my life that was growing and evolving."

He's even truthful when it comes to his own failings. "My sequels haven't been better than the originals. I haven't made a Godfather II yet," he says. There is clear admiration here for his friend and peer Francis Ford Coppola. "Godfather II is the crème de la crème. And I've never done that. For me. Not maybe the audience – a lot think the third Indiana Jones is the best Indiana Jones. But I always felt all my sequels after Raiders of the Lost Ark weren't as good."

If this Hollywood Peter Pan eventually grew up, beginning with 1993's Oscar-winning masterwork, Schindler's List, he estimates his movies took an even darker turn after the 9/11 terror attacks. "9/11 changed a lot for me. It changed a lot for everybody in the world. And my films did grow darker after 9/11. Minority Report was a very dark look at the future, and certainly War of the Worlds, which was a very direct reference to 9/11. It was a real post-9/11 story. Not intended that way, but that's the way it turned out. So I think the world has a great impact on how it colours my movies. I think that's a good sign. It just means I'm changing by being aware of what's happening."

There were lighter films in the period – not least his exuberant true-life con-artist caper Catch Me If You Can, arguably his best film of the decade (and another work dealing with father-son dynamic). But certainly, movies like 2005's true-life Munich – set in the wake of the assassination of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics – suggest Spielberg has become more political as he's got older.

So has he become more political? "Everybody does," he replies, skirting the question. "I know so many directors... Marty is more political. You can't believe it – Scorsese, political? – because he's a film-freak. But Marty is more political now than he ever was before. Everybody I grew up with, of my generation of film-makers, started out being cineastes, and now we are very aware of everything that is happening around us. I think once you have children that starts to happen anyway."

His next film will again deal with politics, as well as history. Lincoln stars Daniel Day-Lewis as the 16th President of the United States. "My interest in Lincoln really stemmed from learning about Lincoln as a student [which we were taught] from the third grade on." He refuses to talk further, but does admit that he will then make Robopocalypse. "It's a big huge crowd-pleaser, science fiction futuristic movie about a robot war between people and machines." The inner child, it seems, is still alive and kicking.

'War Horse' opens on Friday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments