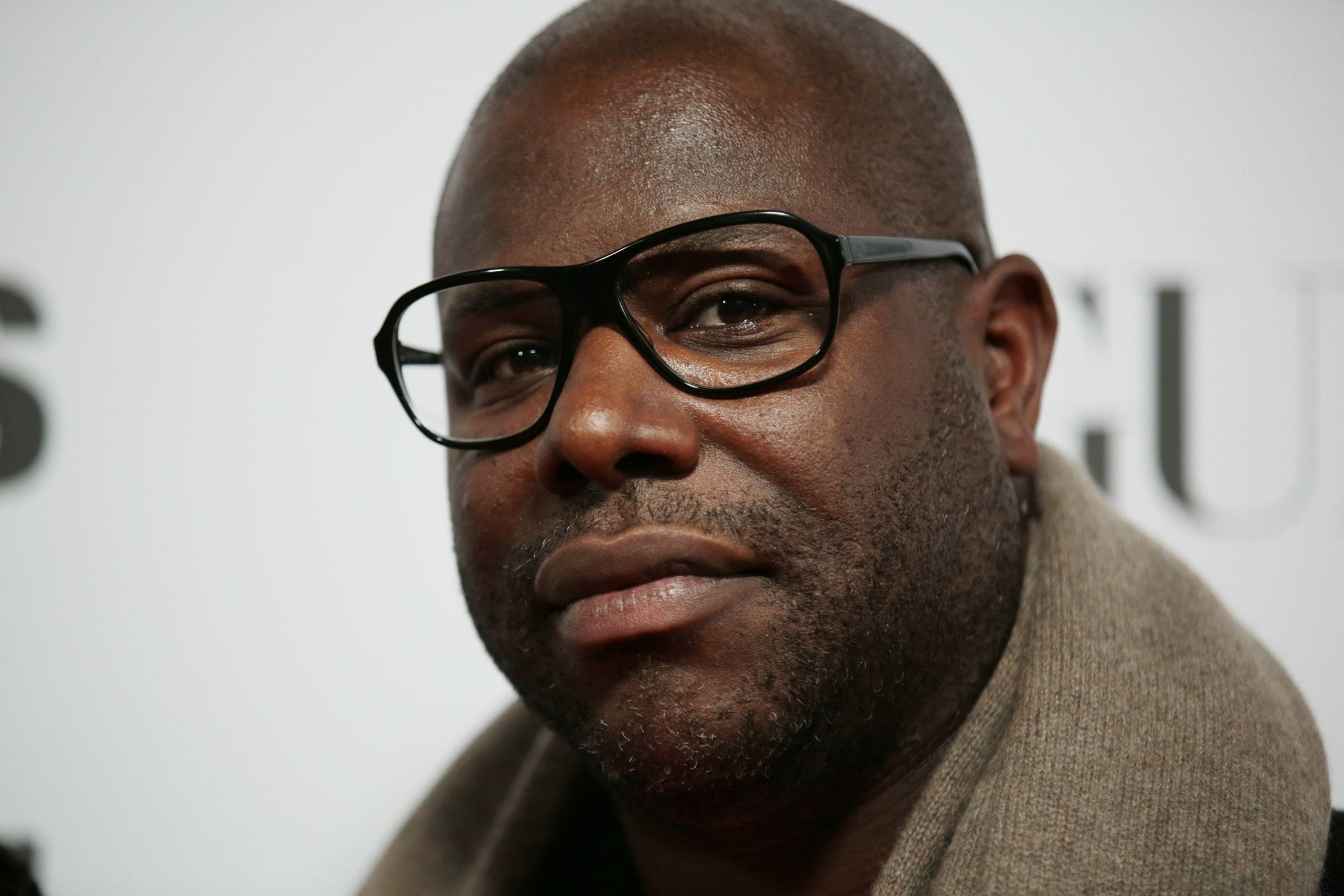

Steve McQueen interview: 'Men are a little bit tone deaf to certain aspects of feminism'

The director takes issue with male critics’ reaction to his new film ‘Widows’. He tells Clarisse Loughrey why

Steve McQueen is troubled by the critical reaction to his latest film, Widows. Not because it’s been negative – in fact, as with most of his movies, it’s been incredibly well received – but because so few male critics have grasped what the film’s true intentions are. “They miss the biggest point,” says the 49-year-old. He lets out a sigh. “That’s been the most interesting thing so far as the response to the picture is concerned, that men are a little bit tone deaf to certain aspects of feminism. I think that has been very, very illuminating to me.”

Most of the reviews for Widows have, as is almost always the case, been written by men. And that same majority has revelled in the film as a sleek, high-brow piece of popcorn entertainment: a surprise move away from the heavy, serious work of McQueen’s past and into broader (albeit still politically conscious) thriller fare.

A remake of Lynda La Plante’s ITV series of the early Eighties, Widows opens on the death of three men in a failed heist attempt, as the women they leave behind – played by Viola Davis, Michelle Rodriguez and Elizabeth Debicki – step up to finish the job, enlisting the aid of Cynthia Erivo’s getaway driver.

And yet, what’s been largely drowned out of the discourse surrounding the film is how striking this union between women is – and the importance of what it represents. “Men are engaged with it because it’s a thriller,” says McQueen, “but I think women are also engaged with it because they’re seeing themselves for the first time in certain situations they’ve never seen themselves in before.”

Widows is a story about those who have been underestimated for too long. It’s about what they’re capable of when the situation demands it, and what they can achieve when they put their trust in each other. As Davis’s ringleader Veronica tells her team, “no one thinks we have the balls to pull this off” – and that’s precisely why she knows they will.

Widows is a conscious shift of the spotlight, with a cast of four women who would never normally be seen working together in a Hollywood film, let alone so competently and coolly, without infighting or pettiness. “Often in movies, women hate each other,” says McQueen. “The fact that these people come together, that they respect each other – it’s very bold and very powerful.”

McQueen has spent his career driven by a desire to confront the unspoken. He faced the Troubles in his debut Hunger (2008), sex addiction in Shame (2011), and the racism embedded in America’s history in 12 Years a Slave (2013) – all to resounding critical and, more surprisingly, financial success (12 Years a Slave took home $188m/£145m at the box office as well as the Oscar for Best Picture).

His work as a visual artist has been no less successful. After a childhood spent in Hanwell, west London, McQueen took up studies at the Chelsea College of Arts, Goldsmiths College at the University of London, and briefly, New York University’s Tisch School of Arts. After a series of startling visual works, from his debut Bear (1993), which depicted a strange, ambiguous wrestling match, to Deadpan (1997), which restaged one of Buster Keaton’s most famous stunts, McQueen was awarded the Turner Prize in 1999 for Deadpan.

However, Widows is still new ground for McQueen, in that it’s his first film to centre on female characters. And there’s a sense that the picture’s handling by male critics has come as a surprise to him. Our conversation is varied – we discuss his collaboration with the film’s co-screenwriter Gillian Flynn and the political echoes of its Chicago setting – but time and time again, McQueen will drift back to the same thoughts.

He apologises for the derailments, but there is an anger there that he cannot ignore. “That’s why we need more women critics,” he says. “It’s a fact! Because, if male critics can’t see what’s right in front of them which, unfortunately, a lot don’t, not saying all, it’s kind of sad. You cannot have a situation where people are engaging with the world and judging how people reflect on the world, with it being 90 per cent men. The response to the film has been fantastic, but let’s focus on what it’s meant to be about!”

There is nothing to apologise for. This is the gift of getting to sit down with someone like McQueen, who sees his every word as an extension of his work. To him, an interview on a press tour isn’t the obligation of a contract; it’s not something to be suffered through until the day is over and it’s time for drinks at the hotel bar. It’s almost as if his entire being is his art, and so the words he offers me are as carefully considered as any of his work.

He’ll gallop through certain sentences, when an idea has taken hold of him. Sometimes, he’ll stop dead in his tracks, pause, and begin anew. At one point, defeated by one of his own ideas, he throws his hands up in the air and begs: “Make me sound good!” That, of course, is not something I need to do. And I’m happy, too, to share in his frustrations, because what he’s saying feels vital.

The past few months have seen several notable Hollywood figures make pronouncements on film criticism’s gender imbalance. Brie Larson took to the stage at LA’s Women in Film convention to stress a need for criticism to better reflect the world we live in, adding: “I don’t need a 40-year-old white dude to tell me what didn’t work about A Wrinkle in Time.”

Her comments were later elaborated on by the cast of Ocean’s 8, who argued the dominance of male critics was “unfair”, especially for female-led or directed films. A study later confirmed this, with male critics, on average, rating female-led films 10 per cent lower than female critics.

However, the focus on films with mixed critical receptions, such as A Wrinkle in Time or Ocean’s 8, has led to accusations of defensiveness. And so, McQueen stands as a rare example of a director who is still vocal about the male-dominated reaction to his film, despite the almost unanimously positive reviews (it currently holds 96 per cent on Rotten Tomatoes).

As the interview goes on, it’s clear McQueen’s frustrations reflect the fact he’s proud of this film. Or, more crucially, he’s proud of the women in this film. Any talk of his cast is accompanied by a cascade of words like “amazing”, “extraordinary”, or “exceptional”, and he sees a poignancy in their presence together on film. “Look at these four women,” he says. “Elizabeth Debicki, 6ft 4in; Cynthia Erivo, 5ft, dark-skinned black woman; Michelle Rodriguez, tomboy Latina with attitude; Viola Davis, middle-aged, dark-skinned black woman. These are not your typical Hollywood women, but these are women that I know, whom I engage with every day.

“All those four women have had knockbacks in this industry, one way or another, because of their appearance,” he continues. “All of them.” Actresses like Davis and Erivo are constantly stereotyped by Hollywood, as McQueen adds: “They’re not seen as sexual, they’re seen as holier than thou. They’re sort of not deemed as women.”

But here, Davis’s character is shown in a loving, sexual relationship with husband (Liam Neeson), while Erivo is also given an onscreen partner. They shared a joke between the three of them, where the director would tell them: “I’m giving you a vagina!” Widows, in McQueen’s mind, was the opportunity for his cast to stop pretending, and “just be themselves, for f***’s sake!”

This sense of unity between the four women is also crucial to the film itself. Although the quartet in the ITV series were all depicted as working class, McQueen felt it was important for his characters to come from diverse backgrounds, in terms of both race and class. It serves both as a reflection of Chicago’s deep segregation and as an empowering statement, when these women eventually come together despite (and because of) their differences.

“Because right now, politically, we find ourselves in a bubble – this bubble, or that bubble – no one’s engaging with each other, because we don’t think we can have anything in common,” he says. “Which is not the truth. And that’s why people are coming along and taking the power, and doing what they want. Because it’s dividing more. So everyone has to come together in order to make things work.”

Indeed, despite the bleakness that has characterised so much of McQueen’s work, he’s hopeful about the future. “The future is the only thing we’ve got,” he says. Even his despair over the lack of female critics ends on an upbeat note. As we part ways, he leaves me with the words: “Change the world! You have the power.”

Widows is released in UK cinemas on 6 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks