Star Wars Episode 7 is being shot on film - and now Kodak is launching a last-ditch bid to keep celluloid alive

Bob Weinstein is among the Hollywood suits who have been working with Kodak to commit to long-term orders for film. Simon Usborne wonders what all the fuss is about

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One thing unites the films Argo, Django Unchained and The Dark Knight Rises beyond their critical and box office success: they were shot using film. This makes them rare in the digital age but, as part of a campaign to reverse a precipitous decline, studios have entered secret negotiations in a desperate attempt to save celluloid.

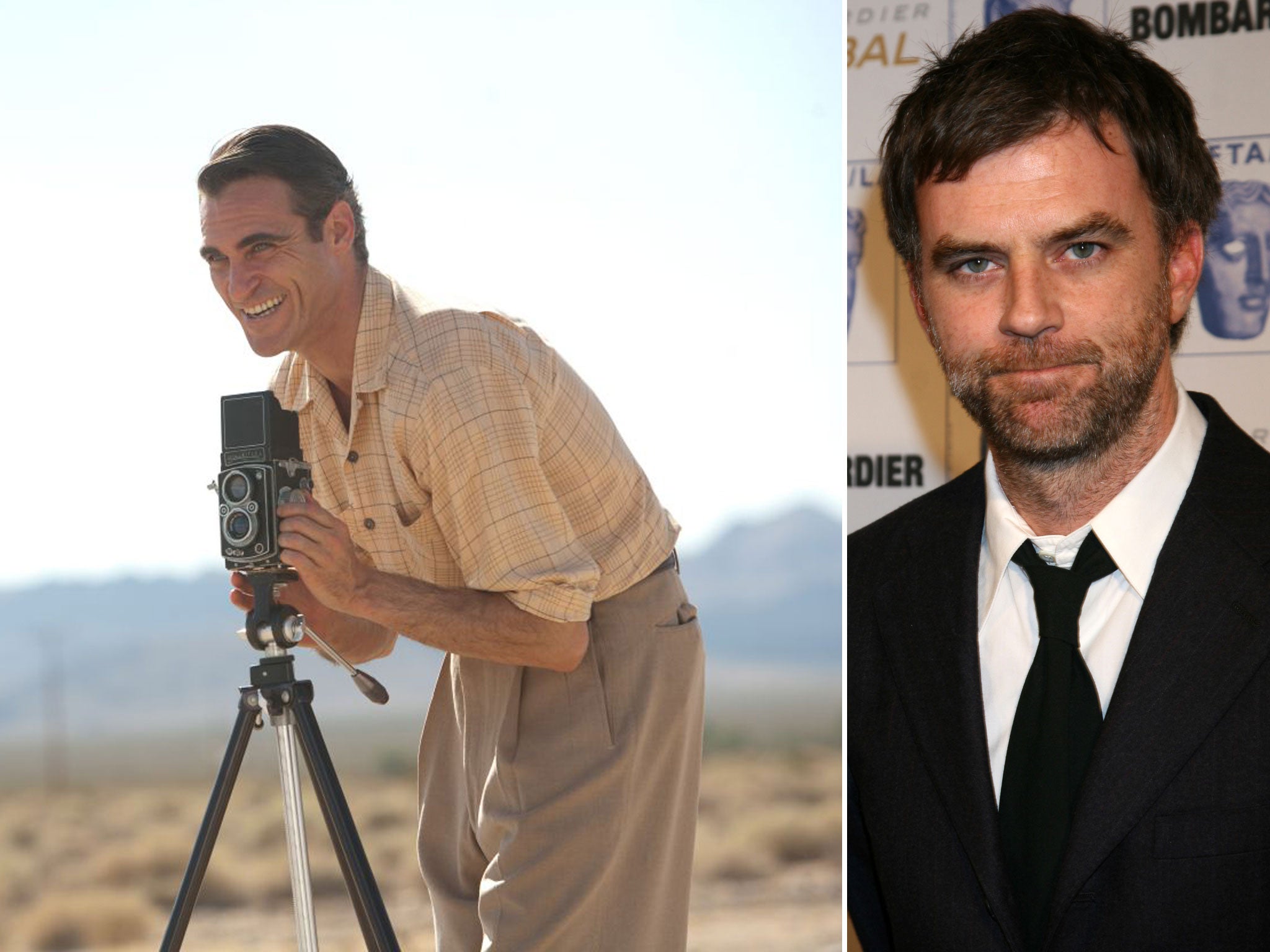

Bob Weinstein, co-chairman of Weinstein Co, is among the Hollywood suits who have been working with Kodak to commit to long-term orders for film. As recently as 2006, Kodak was selling 12.4 billion feet of movie film a year. This year, it expects to sell 449 million feet, or just one 25th of the amount. It became the last big company making film after Fujifilm canned its production last year.

"It's a financial commitment, no doubt about it," Weinstein told the Wall Street Journal. "But I don't think we could look some of our film-makers in the eyes if we didn't do it."

Quentin Tarantino is among those directors who have lobbied Weinstein to act, alongside Judd Apatow and Christopher Nolan, the British director of the recent Batman films. J J Abrams is now shooting Star Wars Episode VII on film, partly in a move to distance the work from the 2002 sequel Attack of the Clones, the first movie to be shot digitally. Film "sets the standard for quality", Abrams said. "There's something about [it] that is undeniably beautiful, undeniably organic and natural and real."

The news that powerful names, including those who control the money, are committing to film, delights those who have been campaigning for years to rescue it. Tacita Dean, the renowned British artist, shot a film inside a Kodak factory in France in 2006. It closed weeks later. "Film", her 2012 installation in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern in London, was as much a campaigning work as a demonstration of the medium's unique qualities.

"People make the analogy of oil and watercolour in painting but it's way more explicit than that," she says from her Berlin studio. "There are enormous qualitative differences. Film looks different, it captures light differently. There is more depth and it copes much better with blacks."

Moreover, in the way the shutter-happy holidaymaker's approach to photography has changed, film requires a different behaviour because the results cannot be instantly reviewed. "Digital has become like a template," says Dean, who is a leading campaigner behind SaveFilm.org. "You record it and then add to it in post-production and that just makes it different."

But these advantages are drawing film-makers who remain passionate about film. Rob Hardy directed photography on The Invisible Woman, Broken and Shadow Dancer. He went digital for the first time to shoot Ex Machina, an artificial-intelligence love story written and directed by Alex Garland. It is due for release next year.

"It's a human story with a subtle element of artificiality," Hardy says by phone. "From a photographic perspective I wanted something heightened that retained a natural feel, something digital cameras could provide."

Conversely, when Hardy shot The Invisible Woman, a period drama directed by Ralph Fiennes released last year, "there was no question that we needed the texture, atmosphere and authenticity of that period, and digital absolutely did not suit that".

Roger Deakins is the veteran British cinematographer behind films including The Shawshank Redemption and Fargo. In 2011, he switched to digital to shoot In Time, a sci-fi thriller. It "gives me a lot more options", he said at the time. "It's got more latitude, it's got better colour rendition. It's faster. I can immediately see what I'm recording.

"Am I nostalgic for film? I mean, it's had a good run, hasn't it? You know, I'm not nostalgic for a technology. I'm nostalgic for the kind of films that used to be made that aren't being made now."

Those on both sides of the debate argue there should be room for both media. "It's a question of having creative choice and that's what this campaign should be about," Hardy says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments