Why OJ Simpson and George Best have transformed the sports documentary genre into something more provocative

With ‘OJ: Made In America’ nominated for an Oscar and the release of ‘Best (George Best: All By Himself)’, the sports documentary genre is undergoing a renaissance, but this time probing into all the complex issues that sport raises

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There was a time when sports documentaries were regarded as a near-redundant genre. They couldn’t capture the intensity or immediacy of “live” events. The ones that were made tended to be triumphalist narratives, telling the stories of great sporting heroes and their triumphs in very bland and predictable fashion.

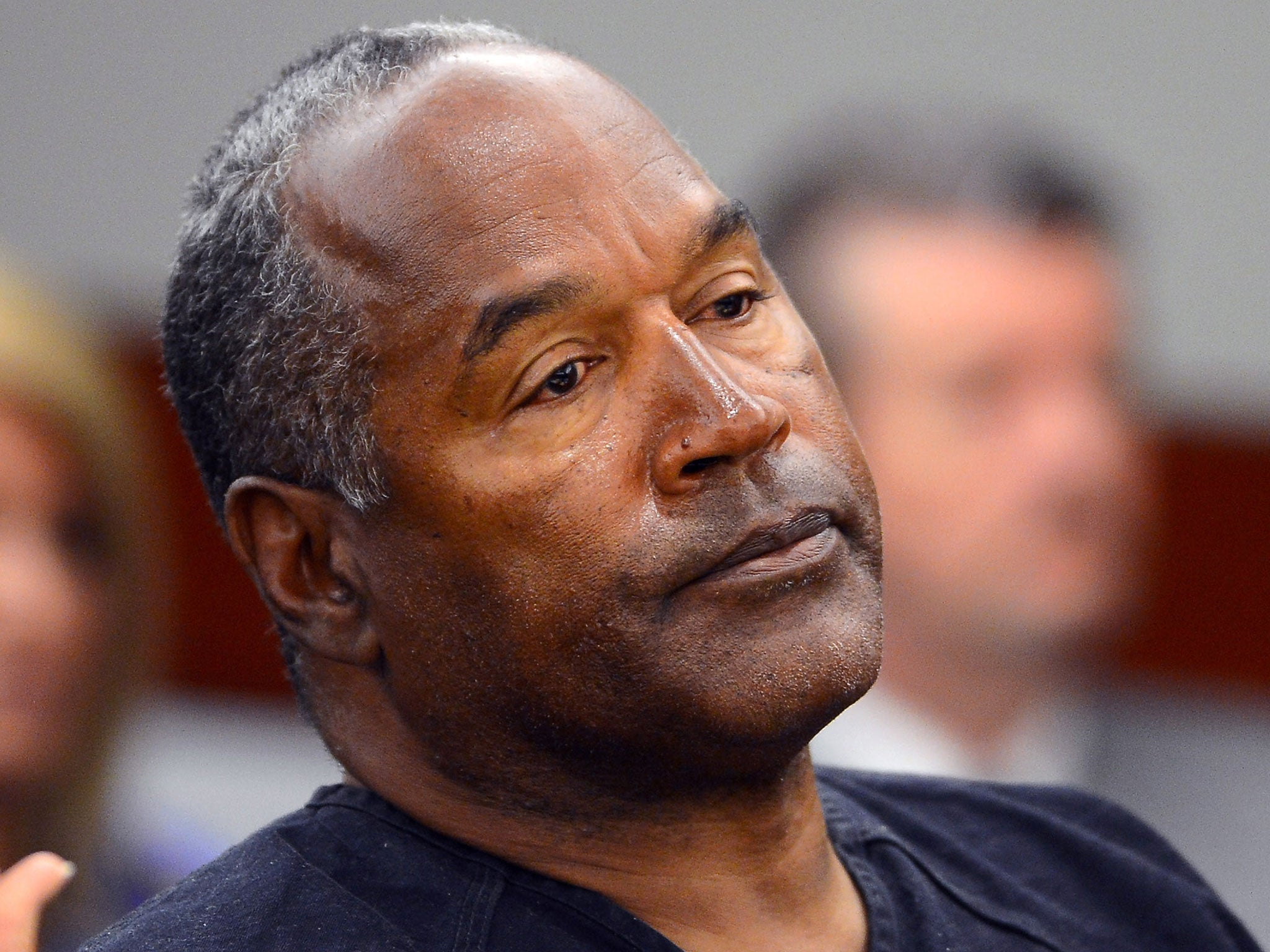

Now, the sports doc is in a golden age. If you wanted to see a single movie last year that told you about the realities of racism in America, the perils of celebrity culture, wife-battering, the flaws in the US legal system, the betrayal of the American dream and of how even the most inspirational figures sometimes have feet of clay, you would turn to Ezra Edelman’s ESPN-backed OJ: Made In America. Many critics would rank Edelman’s probing and extraordinary detailed account of the rise and fall of American football star OJ Simpson as among the very best movies of the year. At 467 minutes, it is certainly one of the longest films to be nominated for an Oscar in either this or any other year.

Sports docs have undergone a transformation in recent times. The change began in earnest in the early 1990s with the releases of two groundbreaking films: Steve James’ Hoop Dreams (1994) and Leon Gast’s When We Were Kings (1996). The former is about two African-American kids from poor backgrounds trying to make the grade in the ultra-competitive world of college basketball. The latter is an account of the “Rumble In The Jungle”, the 1974 World Heavyweight fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in Zaire. The point about both these films is that they were so much more than just sports stories. They touched on class, race, human endurance and the battle to overcome seemingly insuperable odds.

“This is one of the best films about American life that I have ever seen,” critic Roger Ebert famously commented of Hoop Dreams. “Enormously entertaining,” Todd McCarhy enthused about When We Were Kings in Variety while pointing out that the film was looking at “a watershed moment in modern black culture and history”.

Since then, the sports documentary has metamorphosed into a form that allows filmmakers to deal in entertaining but increasingly complex and provocative fashion with all the issues that sports raises.

“I don’t think it did exist as a genre,” Oscar-winning producer John Battsek says of the sports documentary genre before When We We're Kings and Hoop Dreams. “I do think those two films broke the ground - they opened the door for me and others to push on with the idea of trying to create those kind of feature docs.”

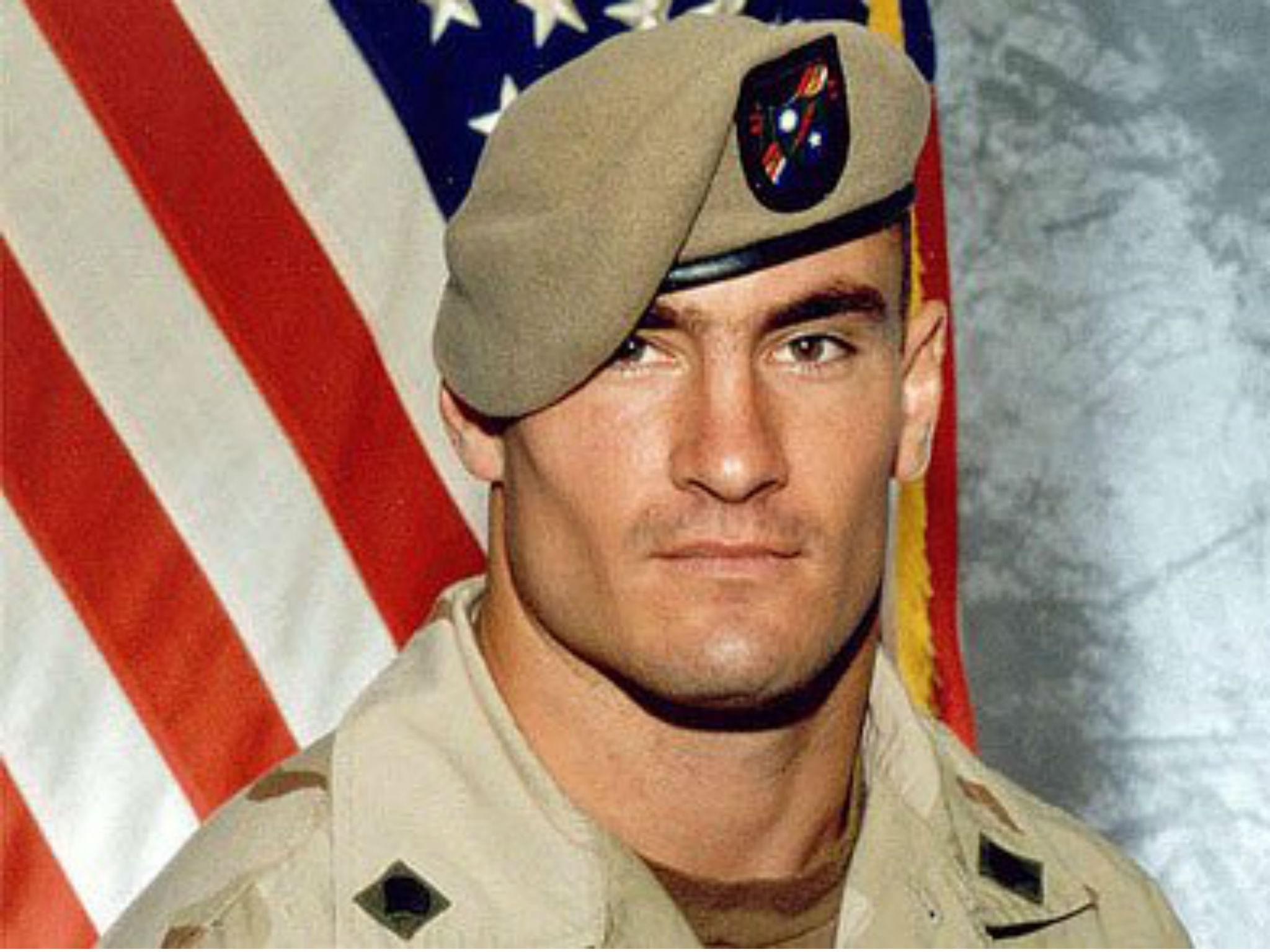

Battsek’s first “sports” documentary, the Oscar-winning One Day In September (directed by Kevin Macdonald), was about the bloody events at the Munich Olympics of 1972, at which 11 members of the Israeli Olympics team were killed by Palestinian terrorist group Black September. This was hardly a sports documentary at all. It was an example of a convulsive political event that took place against a sporting backdrop. Since then Battsek has produced and executive a number of sports docs – films that have sport in the background but deal with complex political and social issues. These include Daniel Gordon’s Hillsborough (2014), Amir Bar-Lev’s The Tillman Story (2010), about the death of an American Football star Pat Tillman, who forsook the NFL to serve with the American army in Afghanistan. The most recent, Best, about the life and times of troubled football star George Best and also directed by Daniel Gordon, is released in British cinemas this week.

“It was really When We Were Kings and then Hoop Dreams that made me very wide-eyed and made me think that there must be so many sporting stories out there that could have that sporting backdrop,” says Battsek. “The trick was to find a story that was much greater than just a sports doc.”

Of course, sports docs were being made long before the 1990s.“Leni” Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938), about the 1936 “Hitler” Olympics, was one of the first. It may induce extreme queasiness because of the Nazi ideology underpinning it, but Riefenstahl found a way of filming sport in a dramatic and involving fashion. She threw in low-angle shots of long-jumpers and used cutting and close-ups in a way that no one else had before. Not that her lessons were learned. It’s instructive to watch the leadenly made film of the 1948 London Olympics in which, if a football or hockey match was being covered, the camera would simply be placed on the halfway line.

Boxing is one sport that filmmakers have always covered in both fiction features and documentaries. Battsek cites Bruce Weber’s Broken Noses (1987) a documentary about a small boxing gym in Portland, as a film that made a particular impression on him.Shot in black and white to the accompaniment of a Chet Baker soundtrack, this was as much a jazz movie as it was a fight film. In the UK, Ron Peck’s Fighters (1991) was a revealing and surprisingly poignant film about boxers in the East End of London pursuing their dreams. The Maysles brothers, masters of so-called verité filmmaking, were behind the probing and moving 1980 film, Muhammad And Larry, about the build-up to the fight between an ageing and self-doubting Muhammad Ali and his lethal younger challenger, Larry Holmes.

Funders like ESPN, Showtime and the BBC are now ready to back sports-themed documentaries that look at their subjects from surprising and oblique angles. For example, there has been a spate of recent docs about cheating in sport. Films on drug taking in sport, why it happens and the broken friendships and emotional chaos it leaves behind, include Alex Gibney’s The Armstrong Lie (2013) (about disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong) and Gordon’s 9.79* (2012), about the 100-metre final at the 1988 Seoul Olympics in which not only the winner Ben Jonson but most of his rivals had, at one time or other, failed a drugs test.

One key difference between sports documentaries and most dramatic features based around sports is that in the latter, the hero or heroine tends to win. Eric Liddell and Ben Abrahams both get their gold medals in Chariots Of Fire. Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky gets all the glory even if Apollo Creed wins on points in the first Rocky movie. In documentaries, by contrast, the protagonists will often come a cropper. They might trip up in a vital race or slip into alcoholism as their careers decline or even die in some foreign war. Part of what makes the films so rewarding is that their insights are so different from what is presented on the sports pages or in TV transmissions. Even when the films are about winning, the back story is always complicated. The elite athletes who we’ve seen on pedestals turn out to be flawed or traumatised. They have their own demons and insecurities.

There’s a certain “blokeishness” to sports docs. They still tend to be made by and amount men. Battsek acknowledges as much. “There is a blokeish aspect to sports in general and it should be obsolete,” he says. There have been relatively few films like Daniel Gordon’s The Fall, looking at the clash between Mary Decker and Zola Budd at the 1984 Olympics, in which the main characters have been females.

At the same time, one of the points about the sports docs is that they pry behind the facades of their subjects, showing their flaws and vulnerabilities.

“When you tell your dark sports story, when you tell the George Best story or the Mary Dekker/Zola Budd story or the Pat Tillman story, there’s something that resonates universally with people. Actually, these elite athletes share a tremendous amount of human connection with ordinary people,” Battsek points out the quality which almost every great sports doc shares, namely the ability to provide a human factor that is so often lost behind the back-page headlines.

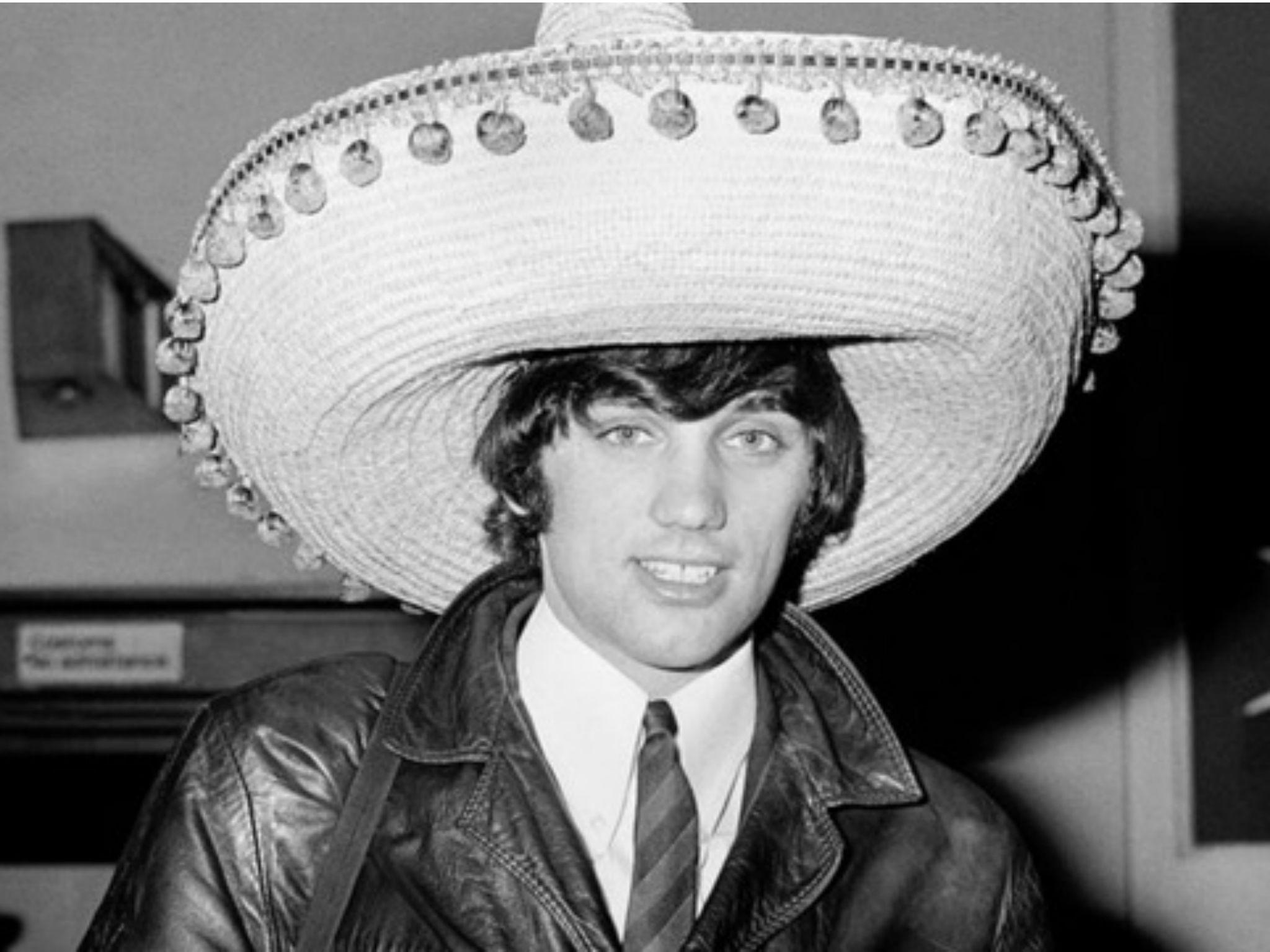

'Best (George Best: All By Himself)' is released on 24 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments