Something’s Got to Give: The story of the Marilyn Monroe film that never got made

The ‘Some Like It Hot’ star was fired from her final role months before her death – the unfinished footage was uncovered decades later. Alexandra Pollard reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wait a minute, sorry, sorry, sorry.” Marilyn Monroe, swathed in a blue dressing gown, her platinum hair still damp, is filming a scene for Something’s Got to Give. She has just fluffed her lines again. “I’m sorry. Shall we … from the beginning? Sorry.” Within a month, the Hollywood star will be fired. Within three months, she’ll be dead. The film will never be completed.

Monroe’s ill-fated final role has been endlessly mythologised in the years since she died, from a barbiturate overdose, at the age of 36. A scene in David Robert Mitchell’s polarising film Under the Silver Lake, in which Riley Keough hoists a bare leg over the side of a swimming pool, is a tribute to one of the film’s few completed scenes.

There isn’t a huge amount else to pay homage to. Monroe hardly ever showed up on set. When she did, the generally accepted narrative is that she was “wilfully disruptive”, unable to remember her lines, and would – in the words of the 1990 documentary Marilyn: Something’s Got to Give – “drift through her scenes in a depressed and drug-induced haze”. The reality is a little more complicated, though.

The studio knew what they were getting into: the actor had a reputation for tardiness, and Billy Wilder – who directed Monroe as Sugar “Kane” Kowalczyk in Some Like It Hot three years earlier – had to hide lines in props on the set for his star to surreptitiously read. When he had a wrap party at his house, she was not invited. Still, her performance in the film made up for it – as did its box office performance. Wilder later admitted that no one could have played Sugar Kane like Monroe.

She hadn’t been on a film set for over a year when she was cast in Something’s Got to Give, a remake of the 1940 screwball comedy My Favorite Wife. Her time off had been plagued by illness and drug addiction: she had undergone surgery for endometriosis, had a cholecystectomy (the removal of her gallbladder) and been briefly hospitalised for depression. The accumulative physical toll had caused her to lose so much weight that she was thinner than she had been in all her adult life. The studio, Twentieth Century Fox, was delighted. “She didn’t have to perform, she just had to look great,” said the film’s producer Henry Weinstein, “and she did.”

But in hindsight, Monroe wasn’t ready – either physically or mentally – to return to acting. She was to play Ellen, a woman who has been stranded on a desert island for years, and who returns to discover that her husband (Dean Martin) has re-married. But from day one of filming, she was absent more than she was present, sending doctor’s notes citing acute sinusitis, high fevers and a chronic virus. When she did turn up, she would have to be coaxed into leaving her trailer.

“She was just fearful of the camera,” said Weinstein, who recalled Monroe throwing up before scenes. Early on, he found her unconscious, in what he described as a barbiturate coma. “I realised that she was even more unstable than I was led to believe,” he said. “And I went to the studio and reported this. I said: ‘I don’t think you can go on with the picture.’ And they said: ‘No, no, it’s OK, we’ll go on.’”

The studio and production team had little sympathy for their star. “Yes this is a sick woman,” said screenwriter Walter Bernstein, “but this is a movie star who’s getting her way, and who doesn’t give a damn about anybody else, and is being destructive and self-destructive.”

But watching Something’s Got to Give’s raw footage – most of which remained unseen for years after the film was scrapped – gives a very different impression. On camera, Monroe is earnest, demure, desperate to get her part right. If she messes up, she apologises profusely. In one scene, hours are wasted as director George Cukor tries, and fails, to get her character’s pet dog to bark on cue. Monroe doesn’t complain once. “He’s getting good!” she laughs as the dog runs rings around the camera crew. She is gentle with her young co-stars, too. Alexandria Heilweil, who played her five-year-old daughter, is told to sit up straight. “If I do the right thing…” says the little girl, but Cukor cuts her off: “Be quiet.” Monroe smiles at her. “You will,” she says gently. It certainly doesn’t seem like the behaviour of someone “wilfully disruptive”.

And there were a few good days. During the now (in)famous swimming pool scene, Ellen takes a late-night skinny dip, attempting to lure her husband out of his bedroom. The set was closed, but a few select photographers were allowed to stay. When Monroe ended up removing the flesh-coloured swimming costume she had been given, they were caught completely off guard. “I had been wearing the suit, but it concealed too much,” she later told the press, “and it would have looked wrong on the screen… The set was closed, all except members of the crew, who were very sweet. I told them to close their eyes or turn their backs, and I think they all did. There was a lifeguard on the set to help me out if I needed him, but I’m not sure it would have worked. He had his eyes closed too.” Photos of Monroe emerging from the pool, sans suit, appeared on magazine covers in over 30 countries. By all accounts, spirits seemed high.

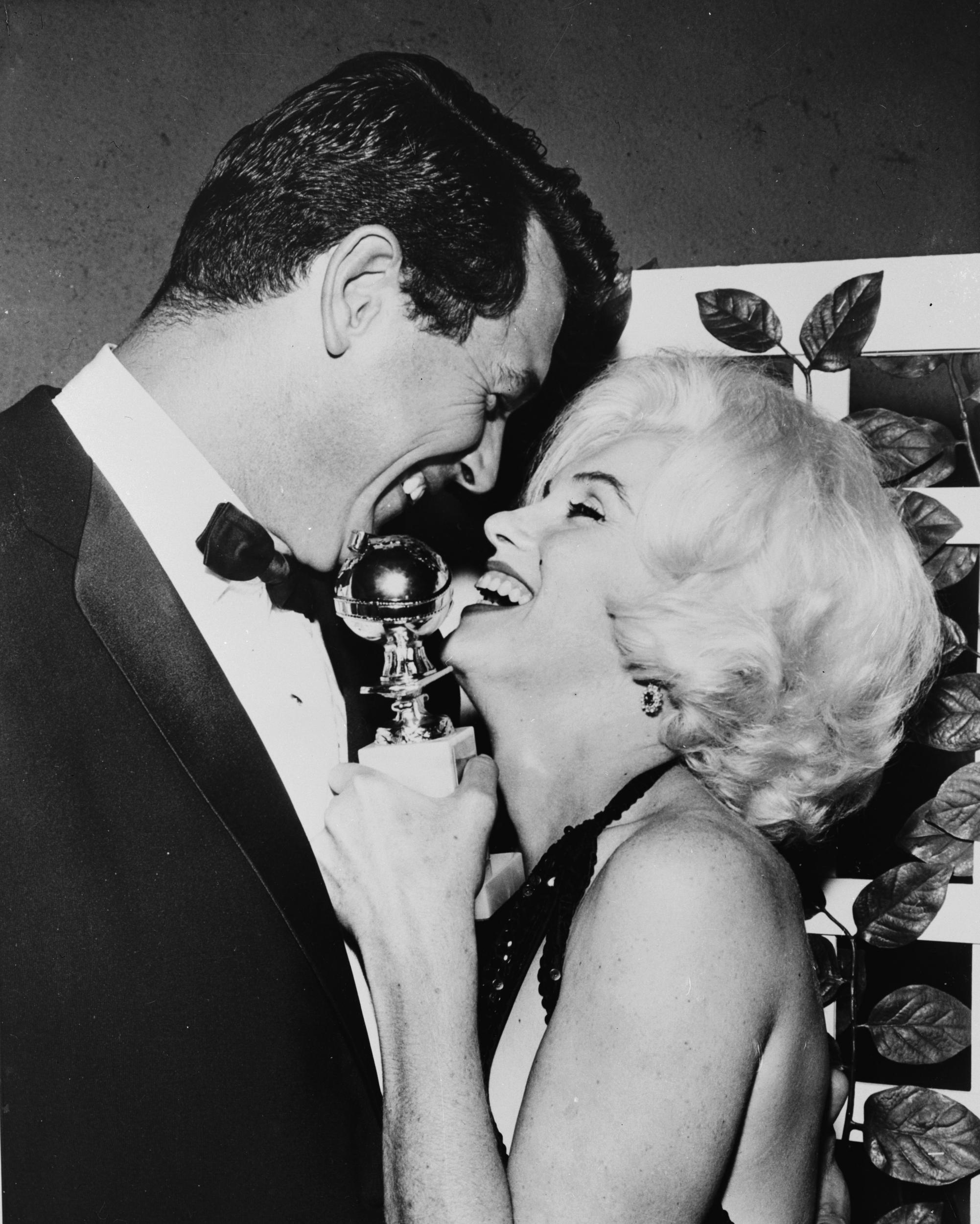

But things went rapidly downhill. On 19 May 1962, having been too sick to work for most of the week, Monroe flew to New York for President John F Kennedy’s birthday celebrations. Her performance there, a sultry rendition of “Happy Birthday”, is now world famous, the image of Monroe in that flesh-coloured, rhinestone dress, into which she had to be sewn, indelibly etched on our collective memory and endlessly parodied in pop-culture. Yet Cukor was furious at the time. Monroe had gained permission to attend the event long before filming began, but he deemed it unacceptable. In June, just a few days after Monroe’s 36th birthday, she was fired for “spectacular absenteeism”, and sued by Fox for $750,000 for “wilful violation of contract”. “Dear George,” wrote Monroe in a telegram to Cukor, “please forgive me, it was not my doing. I had so looked forward to working with you.”

In fact, it may not have been entirely Monroe’s doing. At the same time as Something’s Got to Give was being made, Fox was haemorrhaging money on its three-hour epic Cleopatra (1963). The film was dogged by false starts, re-shoots and delays, and is still – adjusting for inflation – one of the most expensive motion picture ever produced. Its star Elizabeth Taylor, whose $1 million salary was 10 times that of Monroe, refused to turn up before 11am, and was having a stormy affair with her co-star Richard Burton. “Every day’s shoot,” recalled George Cole, who played Flavius, “depended on whether they’d got on well the night before.”

The studio was panicking. “Tensions were high, nerves were frayed, funds were low,” wrote Michelle Vogel in Marilyn Monroe: Her Films, Her Life, “and it’s clear that Something’s Got to Give and Marilyn Monroe were the scapegoats for some very anxious studio executives who felt they were spinning out of control with both productions. The lesser of the films had to go.”

It’s not entirely clear why the studio decided to re-hire Monroe a few months later. Perhaps it’s because Dean Martin refused to work with any other actor, threatening to quit when the studio cast Lee Remick in Monroe’s role. “I have the greatest respect for Miss Lee Remick and her talent, and all the other actresses who were considered for the role,” he said in a statement, “but I signed to do the picture with Marilyn Monroe and I will do it with no one else.” Perhaps they simply realised what they were throwing away. In any case, with Monroe back on board, and with a renegotiated contract, filming was set to re-start in October.

But in August, Marilyn Monroe was found dead. The actor, who was brought up in foster care and had scarcely ever been free from mental health issues and drug addiction, had taken a fatal overdose in her home in Los Angeles. The film was abandoned, and it would be decades until a faded print was discovered, by accident, in a cluttered warehouse.

A few days before she died, Monroe had given an interview to a journalist from Life Magazine, and the subsequent profile was published a few weeks later. It ended with the following: “I had asked if many friends had called up to rally round when she was fired by Fox. There was silence, and sitting very straight, eyes wide and hurt, she had answered with a tiny, ‘No’.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments