Scream 3 was a manic misfire – in the wake of Weinstein, it now feels like an early warning shot

Twenty years ago, Scream 3’s muted critical and commercial response effectively put the blockbuster slasher franchise on ice. But smuggled within it was an angry, provocative takedown of Hollywood, sexual misconduct and the casting couch, writes Adam White

In the opening scene of 1996’s Scream, a naive, all-American girl is seduced over the phone by a slick operator with nefarious motives, and suffers horrifying consequences as a result. Featuring Drew Barrymore in a blonde wig and white jumper – all the better to display the inevitable blood stains – the scene holds an important place in horror movie lore. It is also a metaphor for Hollywood itself. It wasn’t until Scream 3, released four years later, that the subtext became the text.

Along with Quentin Tarantino, Gwyneth Paltrow and Good Will Hunting (1997), the Scream movies were the jewels in the crown for Bob and Harvey Weinstein’s Miramax Films in the 1990s. Released through the brothers’ genre studio Dimension, Scream and Scream 2 (1997) were the most successful slasher movies of all time up until 2018’s Halloween. Smart, satirical and critically beloved, they tapped into a specific strain of Gen-X cool while nodding to the traditions of Agatha Christie-style whodunnits and Friday the 13th-era splatter gore. They were also about celebrity, pop culture and misogyny, anchored by heroic women endlessly targeted by very bad men. That Harvey Weinstein lurked over the producing credits now feels like a horrible kind of irony.

But 20 years after the release of Scream 3, the initial end of the series (before a fourth movie in 2011 and a horrible TV spin-off), it is fascinating to look back on how it first came to a close. Scream 3 didn’t just wrap up the stories of the series’ key figures, but also worked as an angry indictment of sexual misconduct in Hollywood, predatory men and the casting couch. And all under Harvey’s nose.

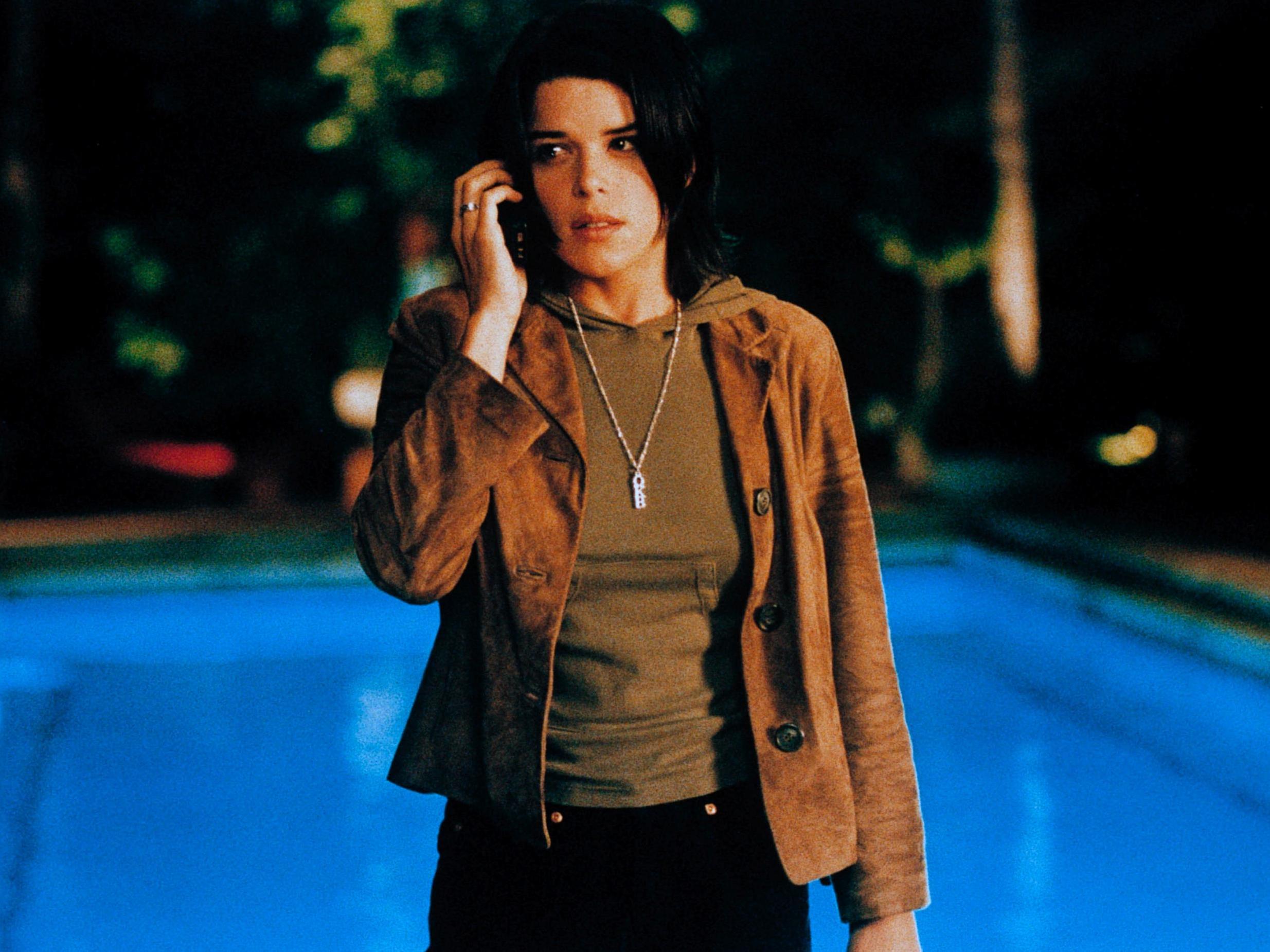

By 2000, the elements that had made the Scream films such a sensation, from their casts of recognisable TV stars to their knowing awareness of genre cliché, had been mimicked in a number of other movies, among them I Know What You Did Last Summer and Urban Legend. Series creator Kevin Williamson and star Neve Campbell, who played the franchise’s haunted heroine Sidney Prescott, were also eager to move on. But the Weinsteins wanted a third movie regardless, seeing the Scream series as the cinematic equivalent of printing money.

Things were different the third time around, however. Because of a renegotiated contract, Campbell was only on set for 20 days, reducing Sidney to a supporting player in the completed film. Director Wes Craven only agreed to return if the Weinsteins financed his 1999 passion project – an out-of-character inspirational drama called Music of the Heart starring Meryl Streep. Williamson, then at the peak of his powers as the creator of Dawson’s Creek, also had commitments elsewhere, leaving Scream 3’s script to be written by relative newcomer Ehren Kruger. He would struggle to emulate Williamson’s sharp and playful tone.

The resulting film is a manic misfire, lacking any of the emotional stakes of its two predecessors and awash in shrill comedy. It ends up playing like a bloodier, zanier episode of Scooby-Doo, with characters sprinting back and forth while a masked murderer bumps into things. By the time Scream 4 arrived 11 years later, with Williamson returning to the fold and Campbell more invested as an actor, its immediate predecessor had been largely forgotten. Then 2017 happened.

After dozens of women accused Harvey Weinstein of crimes including harassment, assault and rape (he has denied all allegations of non-consensual sex), many were inspired to take a second glance at discrete historical allusions to his alleged behaviour. TV series like 30 Rock and Entourage had lampooned his reputation, and comics such as Seth MacFarlane had previously joked about transactional relationships between the producer and aspiring female actors. But Scream 3 was the only project with which Weinstein was significantly involved that nodded towards behaviour he was later accused of propagating.

Scream 3 plays out against the backdrop of filming for Stab 3, a slasher movie based on the “real life” victims of the franchise’s masked murderer Ghostface. Sidney, who had previously survived two attempts on her life, is lured out of hiding when Stab 3 cast members start getting murdered in conjunction with their fates in the film’s script. Such a premise gives way to a number of in-jokes about the Scream franchise, but also pointed commentary on the nature of Hollywood.

Transactional sex is a key plot point. Emily Mortimer’s Angelina, an aspiring actor said to have won the role of Sidney in a nationwide casting call, is accused of having “stepped on any poor girl that got in her way”. Shortly before she is murdered, she confesses to having slept with the film’s producer in order to get the part. Parker Posey’s Jennifer, the eccentric actor embodying Stab’s version of tabloid reporter Gale Weathers (Courteney Cox), alludes to a fling with the film’s director.

Carrie Fisher, in a movie-stealing cameo, portrays a Hollywood studio employee named Bianca Burnette who looks uncannily like Carrie Fisher, and rolls her eyes at any mention of the fact. “I was up for Princess Leia,” Bianca explains, in dialogue Fisher reportedly wrote herself. “I was this close. So, who gets it? The one who sleeps with George Lucas.”

In the film’s most uncomfortable scene, studio president John Milton (a slimy Lance Henriksen) attempts to allay the fears of Stab 3’s director when production is shut down. “Hollywood is full of criminals whose careers are flourishing,” Milton remarks. Shortly afterwards, he is confronted with evidence that he was involved in an assault years before against Sidney’s late mother Maureen, once an aspiring actor known as Rina Reynolds.

Milton calls her “a nobody”, and claims that she was fully complicit in the horror that unfolded after she attended one of his notorious parties. “Rina knew what they were,” he explains. “It was for girls like her to meet men. Men who could get them parts, if they made the right impression. Nothing happened to her that she didn’t invite in one way or another, no matter what she said afterwards.”

“Things got out of hand,” he continues. “Maybe they did take advantage of her. You know, maybe the sad truth is that this is not the city for innocents. No charges were brought, and the bottom line is that Rina Reynolds wouldn’t play by the rules. You wanna get ahead in Hollywood? You gotta play the game or go home.” Milton even offers the excuse that it was a different era. “It was in the Seventies,” he protests. “Everything was different.”

In 2017, shortly after the first stories of Weinstein’s alleged behaviour appeared in The New York Times and The New Yorker, the Miramax mogul took a similar approach to his own accusations. “I appreciate the way I’ve behaved with colleagues in the past has caused a lot of pain, and I sincerely apologise for it,” he said in a statement to The New York Times. Lisa Bloom, his lawyer at the time, referred to Weinstein as “an old dinosaur learning new ways”.

In 2000, there was no acknowledgment of the strange parallels between Weinstein and Scream 3’s plot in the press, or even surprise that themes of sexual predation and the horrors of the casting couch were somehow major storylines in a throwaway slasher sequel. Dimension Films’ projects were largely overseen by Bob Weinstein, with Harvey distracted by more Oscar-friendly material over at Miramax, but it still didn’t explain how such an inflammatory subject matter could be smuggled into one of their own movies.

Answers may exist in the tortured production of the film, with no one particularly wanting to be there, most people only involved following extensive negotiations and bartering. Watched today, Scream 3 is a relentlessly bleak movie, with a weary cynicism about creativity, the film industry and fame. “To me,” Patrick Dempsey’s Detective Kincaid tells Sidney at one point, “Hollywood is about death.”

In 1997, Rose McGowan, who became a mainstream star as a result of the first Scream film, was allegedly raped in a hotel room by Weinstein. In her 2018 book Brave, she describes the set of Scream as one of the last times she felt truly happy in Hollywood. “The set of Scream was a refuge for me,” she writes. “Wes Craven was a special and complex man … He treated us actors like his equals, and it was a very special environment. [He] was so kind, a true gentleman. I thought all my movies with big directors were going to be like this one. I was wrong.”

Craven died in 2015, and never went into detail about his relationship with the Weinsteins, or how much he knew about Harvey’s alleged crimes. He certainly had a fractured relationship with Bob, at least, clashing with him during the filming of Scream over the apparent need to dress Barrymore in a “racier” outfit and fit her with a different wig. Craven was also threatened with being fired from the movie days into production, only retaining his job after screening the film’s opening sequence (which was luckily shot first) and allaying the Weinstein’s fears over his directorial ability.

But it means that Scream 3, one of Craven’s final films, exists as a potential indication of his feelings. The film feels like a rebuke to something, or at least a warning. It is about Hollywood as a sham, or where dreams go to die, and exposes the collateral damage the industry leaves in its wake, particularly in its young women.

It would be foolish to consider the film an exposé. It was made at the very peak of Weinstein’s powers in Hollywood, after all. It is, however, a snapshot of a time when his alleged behaviour was a hushed open secret, something people whispered to one another yet would never dare speak about publicly. As a result, Scream 3 only became fascinating two decades after everyone first saw it.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks