Why near-future science fiction like Westworld and Black Mirror is so terrifying: They allow for discussions of the implications of believable changes

The near-future sub-genre, which imagines a future only a short time away, closely aligns itself to the latest developments in science and technology to make it all the more real

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

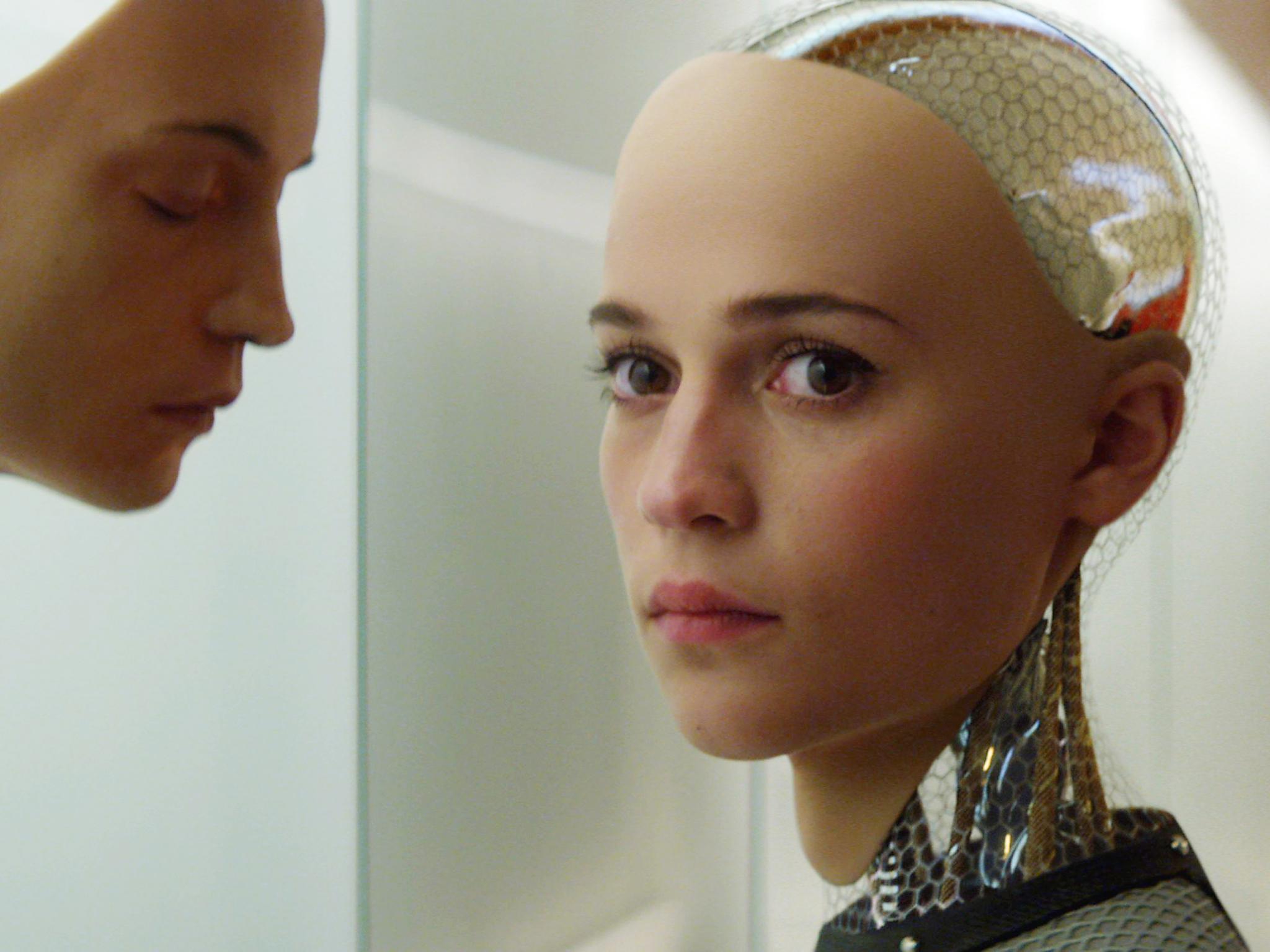

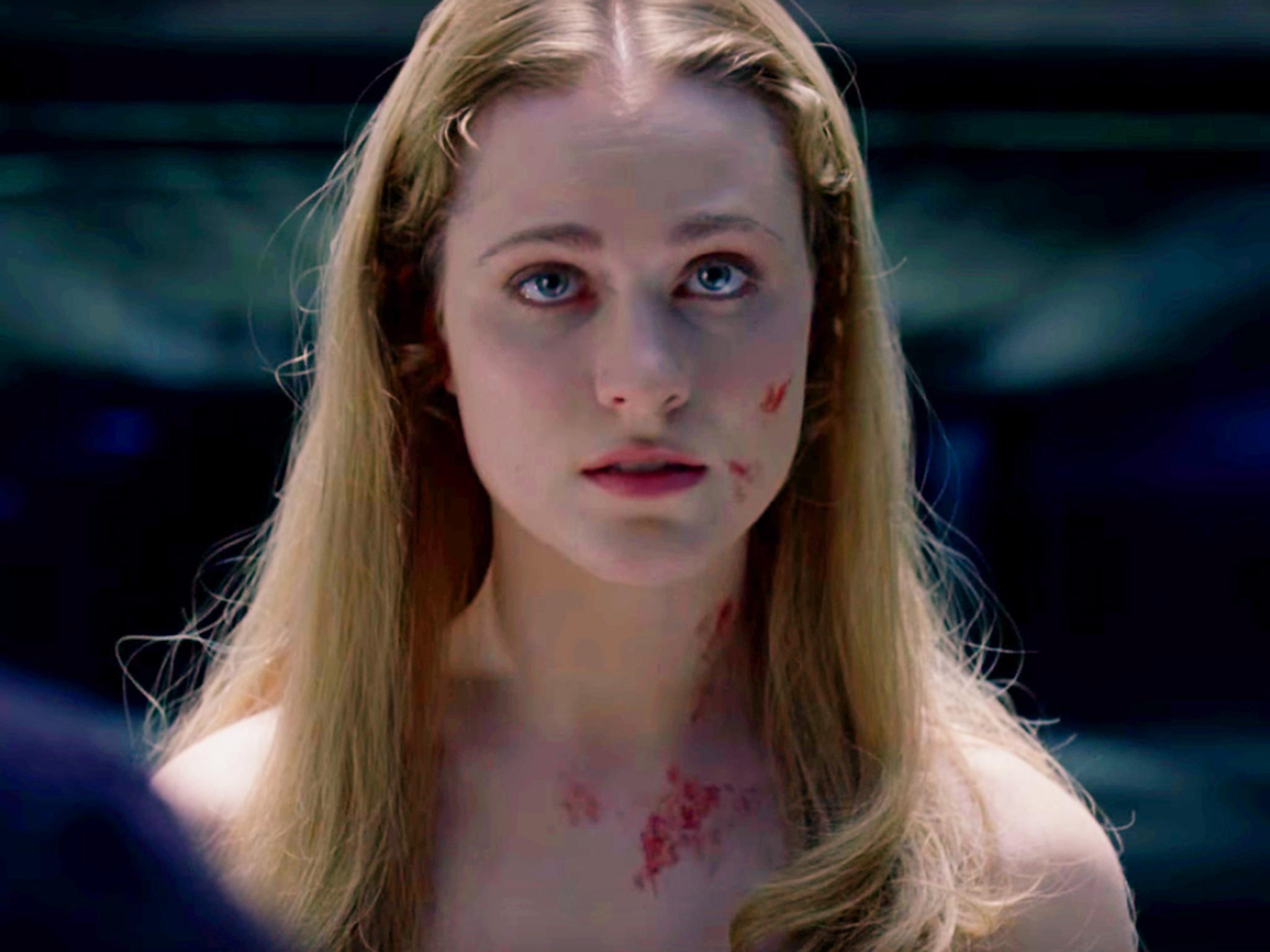

Your support makes all the difference.From Humans to Westworld, from Her to Ex Machina, and from Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D to Black Mirror – near-future science fiction in recent years has given audiences some seriously unsettling and prophetic visions of the future. According to these alternative or imagined futures, we are facing a post-human reality where humans are either rebelled against or replaced by their own creations. These stories propose a future where our lives will be transformed by science and technology, redefining what it is to be human.

The near-future science fiction sub-genre imagines a future only a short time away from the period in which it is produced. Channel 4/AMC’s Humans presents world where advanced technology has led to the development of anthropomorphic robots called Synths that eventually gain consciousness. As the Synths become increasingly indistinguishable from humans, the series explore notions of what it is to be human: societally, culturally, and psychologically.

The second series was particularly concerned with the rights associated with being able to think and feel – and the right to a fair trial. Odi, an outdated NHS caregiving Syth who features in both seasons, chooses a form of suicide (returning to his original setting and rejecting consciousness) as he can’t deal with his new reality.

The robots that inhabit the future theme park in Westworld are also introduced as the playthings of the super-rich. In both cases, the fictional scientists who have created these androids, David Elster (Humans) and Robert Ford (Westworld), purposely design or make provisions for their creations to “become human” with a variety of intentions and both utopian and dystopian possibilities. Both series question the distinction between “real” and “fake” consciousness and the complexities of having a creation come to life.

The challenge of near-future science fiction is that for it to be believable it needs to closely align to the latest developments in science and technology. This means that it has the potential to become obsolete or even come to pass in the lifetime of its creator. News reports and commentaries from scientists such as Stephen Hawking about the dangers of AI and concerns that “humanity could be the architect of its own destruction if it creates a super-intelligence with a will of its own” make the fears articulated on screen seem more real and more frightening.

Some of today’s most popular science fiction takes real-world science and follows it to a possible conclusion, showing it can have a direct impact on each of our lives rather than on just on far future global and intergalactic events. Stories about the near future have proliferated because they are popular with audiences and filmmakers alike. They allow for discussions of the implications of believable changes, such as the artificially intelligent operating system Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson) in the film Her, or the thought-controlled contact lenses that appear in various forms in episodes of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror.

These near-future fictions offer prescient alternatives to other science fiction set in the far future. Consider, for example, the alarming relevance of The Handmaid’s Tale. The novel by Margaret Atwood has been adapted for the small screen and will be broadcast in late April. It is set in a gender-segregated, theocratic republic that is fixated on wealth and class. Women are rated according to their ability to reproduce in a near-future where environmental disasters and rampant sexually transmitted diseases have rendered much of the population infertile.

Amid growing fears of religious conservatism in Trump’s America, Samira Wiley, one of the stars in the new adaptation, says “is showing us the climate we’re living in [and] specifically, women and their bodies and who has control of our bodies”.

Science fiction’s alternate worlds and imagined futures – whether dystopian or utopian – force audiences to look upon their own reality and consider how changes in our societies, technologies, and even our own bodies might take shape and directly influence our own future. Whether presenting a positive or negative future, science fiction attempts to provoke a response, highlighting issues that need to be dealt with by everyone, not just by scientists and governments.

In some senses, science fiction has caught up with us. The idea that we might be able to have android servants, or a personal bond with our computers has been crystallised by Apple’s personal assistant Siri. Research into self-healing implants has brought the prospect of enhancing our bodies to make us more than human ever closer.

The future isn’t as far-fetched as it used to be and it often feels like the futures we see on screen should already be here, or are already here even when they aren’t. We are perhaps shifting from what the futurist Alvin Toffler termed “future shock” to a sort of “past shock”.

Toffler defined future shock as “too much change in too short a period of time” – an overwhelming psychological state that both affects societies and individuals who cannot keep up with and comprehend the speed of technological change that seems to constantly redefine conceptions of the self and society. But we might now be entering an age of “past shock” where we are able to imagine and accept technological changes well before they were developed or even patented. The shock is no longer at the speed of technological change, but rather its apparent slowing, as scientists cannot keep up with our own imagined futures.

As the line between real-world science and science fiction becomes increasingly fluid, the future is closer that it has ever felt before.

Amy C Chambers is research associate in science communication and screen studies atNewcastle University. This article was originally published in The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments