Broken bones, no glory: As Ryan Gosling takes on The Fall Guy, when will stunt performers get their due?

From Buster Keaton to Brad Pitt, Hollywood heroes and their stand-in stuntmen have been risking life and limb (quite literally) to keep us on the edge of our seats for decades. With Gosling starring as a gnarled stuntman in next year’s ‘The Fall Guy’, Geoffrey Macnab hails the hard men you’ve never heard of

For most of cinema history, stunt artists have languished in obscurity. They are dragged under stagecoaches and trampled by horses in old John Ford westerns; they drive chariots round the Colosseum, or jump out of trains and helicopters. Few watching actually know their names. A-listers who’ve been sitting safely in their trailers invariably usurp their glory. That is a state of affairs actor Ryan Gosling seems determined to change. “In most films, the actors get all the credit, but the stunt performers do all the work,” he said earlier this summer. “That ends today.”

Gosling was talking up his next film, The Fall Guy, at industry event CinemaCon. In the action thriller, which hits cinemas in March, he plays a gnarled and ageing stuntman brought in to work on a movie whose main star (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) has just gone missing. Emily Blunt co-stars as the film’s director – and Gosling’s ex.

So are stunt artists finally about to receive some long-overdue recognition from the public and their peers? For this to happen, though, Hollywood will have to come clean about the limitations of most movie stars. For years, we’ve been drip-fed stories of big names boasting about performing their own stunts. But unless they’re Tom Cruise or Jackie Chan, they almost certainly didn’t. Gosling is one of the few A-listers who’s always acknowledged the help he receives from professional stunt artists.

The actor took a stunt driving course before appearing in Nicolas Winding Rein’s existential thriller Drive (2011), and played a motorbike stuntman in Derek Cianfrance’s crime drama The Place Beyond the Pines (2012). Nonetheless, Gosling pointed out last year to Virgin Radio – during promotion for his action film The Gray Man – that “it took a village to make one brave man”. By that, he meant he was only able to look so cool and courageous on screen because he had an “amazing stunt team” that was “curating” his every move behind the scenes.

Hollywood studio bosses have traditionally regarded stunt performers as useful idiots: courageous, foolhardy and eminently expendable. “Most stuntmen were not what you would call intellectuals,” film director Tay Garnett, of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), once witheringly observed. “But if they were, they wouldn’t be stuntmen.”

Things have been slowly changing. In films such as The Fall Guy and Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), in which Brad Pitt played Leonardo DiCaprio’s double, stunt performers are finally being portrayed in a heroic and intelligent light. Certain stunt actors have even graduated to starring roles themselves, notably Zoe Bell, who doubled for Uma Thurman in Tarantino’s Kill Bill films, before leading his follow-up film Death Proof (2007) and making cameos in both his The Hateful Eight (2015) and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. A lot of attention is also being paid currently to a HBO documentary titled David Holmes: The Boy Who Lived. Executive produced by Daniel Radcliffe, it revolves around the actor’s stunt double for the Harry Potter movies, who was paralysed after an accident during the making of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 (2010).

There is growing evidence, then, that stunt artists are being treated with more respect now than at any time since the silent era – when comedians like Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin endured houses collapsing on them, or being dangled from clock towers and slipping on bananas just to keep audiences amused.

Several former stunt coordinators have become respected filmmakers in their own right. The Fall Guy is directed by former stunt artist David Leitch, whose other credits include Deadpool 2 (2018) and Bullet Train (2022). He also co-directed the first John Wick (2014), alongside fellow stunt performer turned filmmaker Chad Stahelski – he was famously Brandon Lee’s stunt double on the comic book adaptation The Crow (1994), and assumed the starring role for several shots when Lee was tragically killed during filming. Both men are also following in the career footsteps of rugged Hollywood 1970s director, Hal Needham.

The title of Needham’s 2011 autobiography is instructive: Stuntman! My Car-Crashing, Plane-Jumping, Bone-Breaking, Death-Defying Hollywood Life. Before he started directing films like Smokey and the Bandit (1977) with his close friend Burt Reynolds, Needham had been one of Hollywood’s most durable and highly paid stuntmen. He was a sharecropper’s son from Arkansas who had grown up dirt poor in the Depression era, before becoming rich by putting his life at risk in movie after movie. He calculated that in the course of his career as a stunt double, he had broken “56 bones, my back twice, punctured a lung, had a shoulder replaced and knocked out a few teeth”. He almost drowned several times too, and came close to being burnt alive.

Needham taught John Wayne how to throw a punch and did stunt work on some exceptional movies, including Billy Wilder’s The Spirit of St Louis (1957), Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970), William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971) and Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974). No one outside of Hollywood knew his name until he graduated to directing, though. He made a series of mostly uninspired action comedies that were generally excoriated by critics. Nonetheless, he earnt far more respect as a filmmaker than he did when he was crashing cars for a living, or being dragged across the desert by horses.

It’s shocking how much credit has been stolen from stunt artists over the years. Mention Ben-Hur (1959) to movie fans and the sequence that immediately springs to mind is the chariot race. It is often hailed as one of the greatest action sequences in cinema history, as well as a highlight of director William Wyler’s career. However, as Wyler testifies in the recent book Hollywood: The Oral History (compiled by authors Sam Wasson and Jeanine Basinger), he actually had very little to do with it. “It was really the work of [stuntman and action director] Yakima Canutt and [second united director] Andrew Marton,” he explained. “They worked about four months doing just nine minutes of film.”

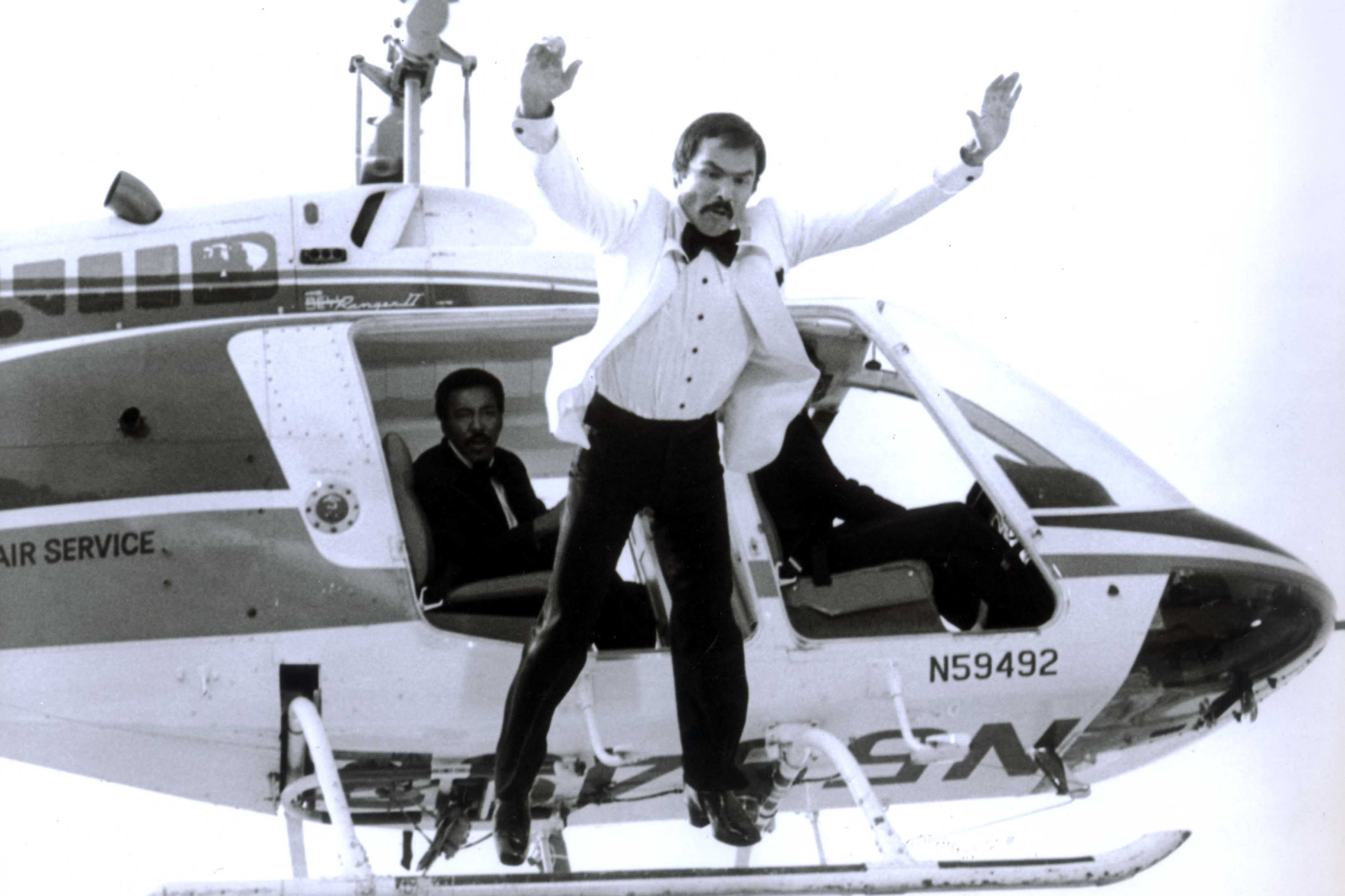

Needham’s movie Hooper (1978), starring Burt Reynolds as a stunt coordinator on a spoof Hollywood action movie, reveals the utter contempt that stunt artists felt for the directors calling the shots – many of whom were also oblivious to the risks they were taking. Hooper portrays its stunt artist hero in a strangely ambivalent fashion. The film opens with Reynolds wrapping his scarred body in bandages as he gets ready to go on set to “perform” yet another motorbike crash. He takes several slugs of whisky, too. The sequence goes perfectly. Reynolds bounces up after the crash, cracks a few jokes with the leading man he is doubling for and flirts with the female stars. The audience, though, is uncomfortably aware of how easily the stunt could have gone wrong. As soon as a stunt is over, Hooper asks for yet more “percs” (highly addictive Percocet prescription painkillers, which he devours as if they’re Smarties.) This is a comedy, but its devil-may-care hero has a bad back, walks with a limp, and is clearly haunted by past traumas.

Audiences still have little idea of the risks taken by stunt artists. Even today, in an era of digital VFX and with exhaustive health and safety guidelines in force, many are continuing to perish. During the making of xXx (2002), Vin Diesel’s stunt double Harry O’Connor hit a bridge during an aerial parachute stunt and died. Earlier this summer, Variety reported that the producers of F9: The Fast Saga (2021) admitted liability over an accident that left stunt performer Joe Watts with life-changing injuries. He had been thrown over a balcony and landed “on a concrete floor from a height of over 20 feet.” Stunt artist Paolo Rigoni died after an accident shooting a ski chase in Bond movie, For Your Eyes Only (1981). Olivia Jackson was driving a motorcycle that collided head-on with a camera during filming of Resident Evil: The Final Chapter (2015), leaving her in a 17-day coma – doctors were also forced to amputate her left arm. During the making of Marvel superhero picture Deadpool 2 (2018), stuntwoman Joi Harris was killed when a motorbike sequence went wrong.

These often catastrophic events tend to be brushed under the carpet. When the films are released and the stars walk up the red carpet at the premiere, there is typically no mention of the tragedies that occurred. But even when stunts don’t go awry, Hollywood seems reluctant to shine a spotlight on their performers.

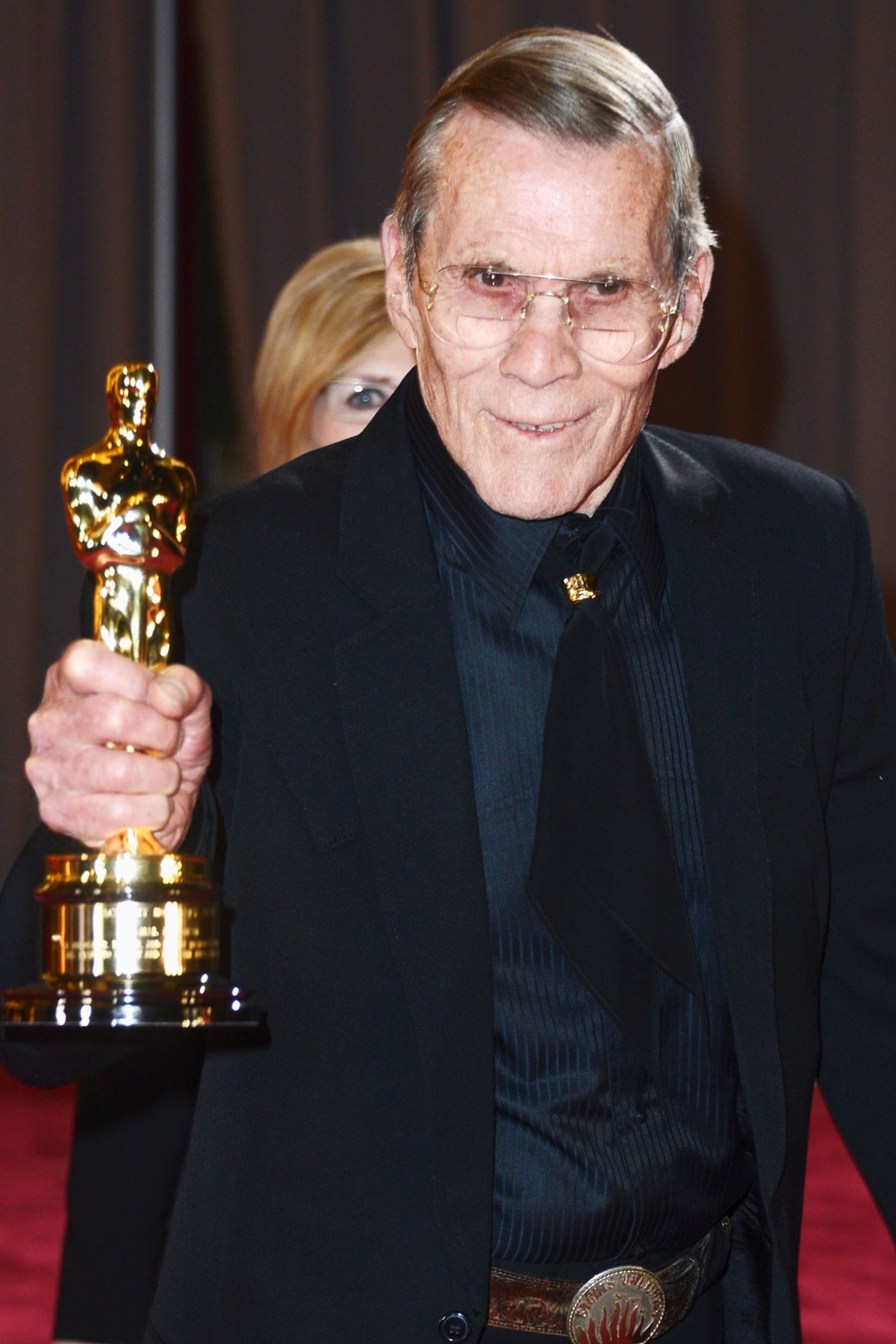

“There has only been one other legendary stuntman, along with Hal, to ever receive an Oscar,” Quentin Tarantino said in 2012, while presenting Needham with an honorary Academy Award. “That entire profession that has done so much for cinema, sometimes at the loss of their life, has only had one other person receive a little gold man.” That was the aforementioned Yakima Canutt, who received an honorary Oscar in 1967.

Stunt artists are the “fall guys” in multiple senses. They’ve been behind many of the most exhilarating moments in cinema history, but audiences and critics remain oblivious to their existence. Gosling’s new movie is unlikely to change this state of affairs overnight, but it should at least alert people to a fundamental part of filmmaking: those unsung heroes risking life and limb purely to dazzle us.

‘David Holmes: The Boy Who Lived’ will be available on Sky Documentaries and Now from 18 November. ‘The Fall Guy’ is in cinemas from 1 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments