‘Suddenly, he was the face of Aids’: Rock Hudson’s tragic diagnosis destroyed his career but changed the world

The star of ‘Pillow Talk’ and ‘All That Heaven Allows’ – who was publicly closeted for much of his fame – defined clean-cut, heterosexual Americana, writes Geoffrey Macnab. A new documentary on his life and death seeks to reappraise his legacy, however, celebrating his private hedonism as well as his sterling, often overlooked talent as an actor

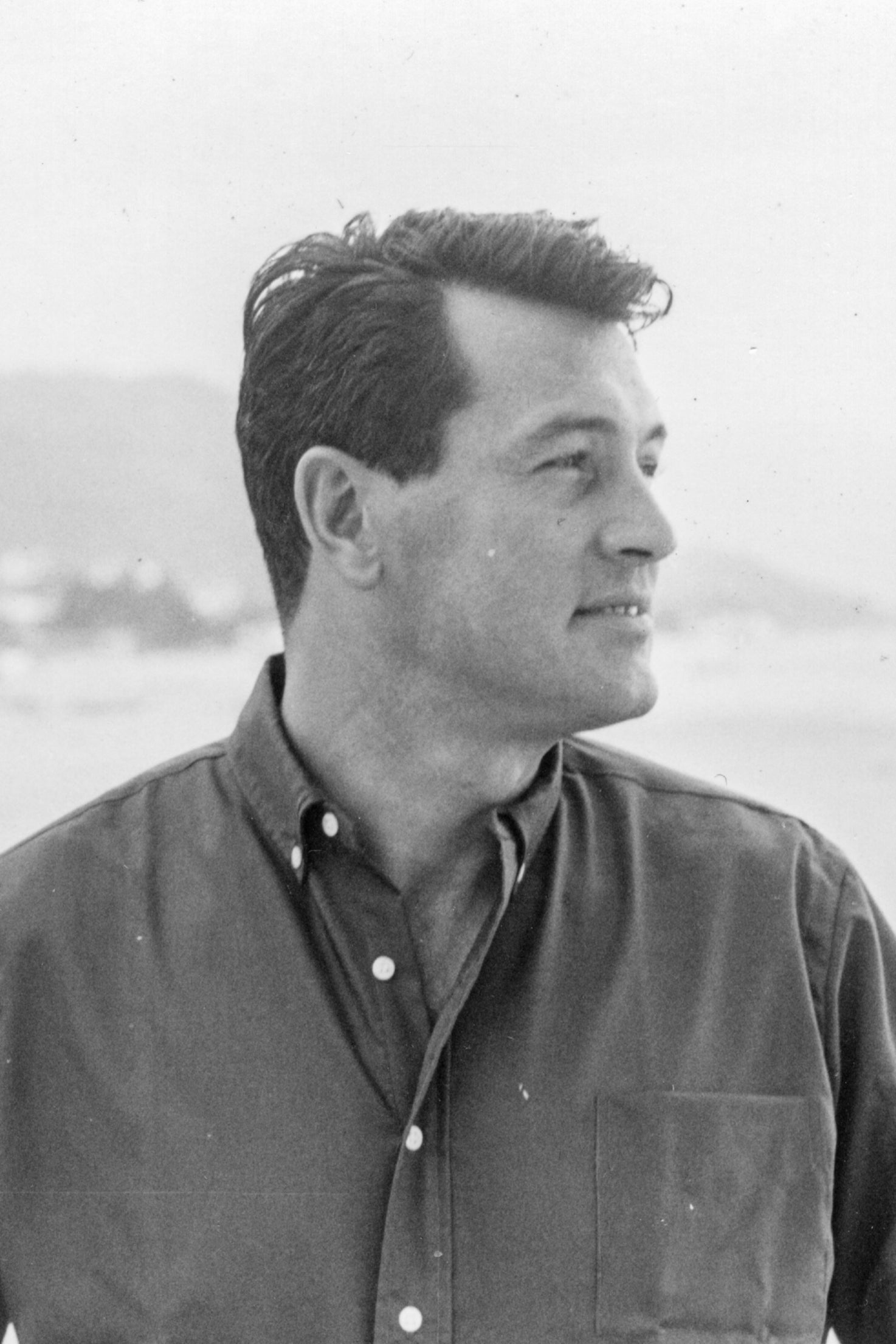

Rock Hudson was rugged, handsome and a strapping 6ft 5in tall. He was as deft in action thrillers as he was in light comedies. Hollywood liked him. He was polite, genial, professional. He was also gay, his 1985 death – at the age of 59 – of an Aids-related illness transforming him into the first celebrity face of the epidemic. Hudson never came out during his lifetime, but many have subsequently called him an “inadvertent activist” due to his cause of death. At a time in which Ronald Reagan’s administration roundly ignored the disease as it tore through America, Hudson put it on the front pages and changed social attitudes in the process.

Almost 40 years on, Hudson is edging back into the limelight. A feature documentary about him, Stephen Kijak’s Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed, is being released later this month, while many of the actor’s best-known films are again available on streaming platforms. It’s a timely moment to assess the career of a star whose credits ranged from westerns with John Wayne, Texan epics with James Dean and, late in his life, even episodes of Dynasty, TV’s schmaltziest soap opera.

“He was really the embodiment of romantic masculinity in films throughout the Fifties and Sixties,” Hudson’s biographer, Mark Griffin – whose book inspired the new documentary – tells me. “For a certain generation of moviegoer, he really defined clean-cut, red-blooded, all-American manhood.”

Hudson never went to drama school. Nonetheless, he was a screen actor who rarely, if ever, struck a phoney note. He had an understated quality. Griffin describes him as “restrained and natural”. To post-war American media, the young star was described in fan magazines as “husky Rock Hudson”, or the “big man from Winnetka”. It is not unfair to suggest that he led a double life. Everything about him, from his sexuality to his screen name (he was born Roy Scherer) involved degrees of subterfuge. He didn’t dare let on to the female fans who wrote him yearning letters addressed to “dear darling Rock” that he wasn’t interested in them in the slightest.

There was little sign, though, that Hudson was tortured by all this hiding in plain sight. In fact, he was something of an enigma to even those who seemed publicly to know him best. “I can’t tell you one thing about him except that he is a nice man,” said Doris Day, who appeared with him in cheery, brightly coloured, mildly risqué romantic comedies such as Pillow Talk (1959) and Send Me No Flowers (1964).

Various filmmakers and authors have attempted to portray Hudson as a tragic figure tormented by his double life, but that’s not really how he saw himself. Hudson may have had his moments of doubt and insecurity beneath his suave façade, but that certainly didn’t stop him enjoying himself. All That Heaven Allowed has plenty of archive footage of Hudson at pool parties, on skiing holidays, or with his friends bronzing themselves at the beach. “He liked to live it up,” Griffin says. “He did have a very active gay life in spite of the fact none of that was out of the closet at that time.”

Suddenly there was this notion that if Rock Hudson, the boy next door, can have Aids, anybody can have it

Griffin tells me that he interviewed dozens of Hudson’s old friends and colleagues during his research for his biography, and not one of them had anything remotely negative to say about him. That might suggest he was a bit bland, yet filmmaker Douglas Sirk, who directed him in swirling 1950s melodramas like Magnificent Obsession (1954) and All That Heaven Allows (1955), spoke of Hudson’s “metaphysical” power on screen. He enjoyed the fact that he could mould him. “At Universal, he was considered a very bad actor,” Sirk once said. “However, he was very eager to learn. His dream was to become a good actor, and I can say, not without pride, that I helped him become one.”

Magnificent Obsession made Hudson a star. He played a wealthy playboy who inadvertently causes the death of a doctor and then falls in love with the man’s widow (Jane Wyman). This was an example of Hudson playing an unwholesome character in a wholesome way; a Prince Charming with intriguing flaws.

There was an obvious irony in the fact that one of Hollywood’s biggest male pin-ups was gay. “He was very willing to work with the publicity department to participate in these fan interviews which created this alternative reality about his life,” Griffin says. On one level, this was simply self-protection. If Hudson had been outed, his career would have been destroyed instantly. All That Heaven Allowed contains shocking insights into how far Hudson’s sleazy and manipulative manager Henry Wilson went to preserve his star’s status. When celebrity scandal magazine Confidential threatened to publish incriminating stories about Hudson, Wilson made a deal with the editors, giving them the names of two other gay actors, Tab Hunter and Rory Calhoun, in exchange for their silence on Hudson. Hunter and Calhoun weren’t such big names and were therefore thrown to the wolves instead.

In the mid-Sixties, Hudson finally tried to crack his image as a rugged, all-American everyman. Many rank his performance in John Frankenheimer’s 1966 feature Seconds as the best and most courageous of his career. This was a Cronenberg-style drama about a conformist, middle-aged banker who undergoes radical surgery and re-invents himself as a hedonistic artist. The film was booed at early screenings and endured a hostile reception upon release, but is now regarded as a cult classic. “It’s like a Rock Hudson autobiography in code,” Griffin suggests. “I think that is his best performance, for my money, alongside Giant.”

In Giant (1956), for which he was nominated for a Best Actor Oscar, Hudson was cast alongside James Dean for the second time, the pair having appeared briefly together in Sirk’s Has Anybody Seen My Gal? (1952). But the two screen icons didn’t get along at all in real life. Giant saw them play love rivals for the attention of Elizabeth Taylor, with Hudson a strapping, wealthy rancher and Dean the surly ranch hand who strikes oil. The enmity between them spilt over off screen. As actors, they came from very different places. Hudson was the wholesome Hollywood sex symbol. Dean was the brooding, mumbling, disaffected loner from New York’s Actors Studio.

Griffin speculates that their mutual loathing may have been caused by Hudson making an overture to Dean that was rebuffed. “What’s intriguing about all of that is that they do come from the same place,” he says. “Both of them were kept by older gay men when they started out in the business.” Dean’s benefactor was advertising executive Rogers Brackett, while Hudson had been helped early in his career by the machiavellian Henry Wilson.

Despite never shying away from gay love affairs in his lifetime, Hudson fiercely withstood coming out publicly. In the new documentary, his friend, Tales of the City writer Armistead Maupin, recalls urging him to talk openly about his sexuality. Hudson continued to resist until, finally, shortly before his death, he was forced to acknowledge his illness.

Perhaps the discretion was wise. The documentary discusses the virulent homophobia that persisted in the early 1980s, as well as the hysteria that surrounded the early days of Aids. Hudson shared a kiss with actor Linda Evans in scenes on Dynasty, at a time when he was already gaunt and ill. Not only was he shunned by fellow actors but no one wanted to go near Evans either, wrongly believing she may have contracted Aids as a result of kissing him. As for Hudson, old friends peeled away from him. Eventually, though, public attitudes began to shift.

“Suddenly, Hudson becomes the face of Aids, [and] almost the poster boy for the entire pandemic which had been raging for a while,” Griffin says. “Before he revealed his diagnosis, I think the public perception of Aids was that it was this ‘minority’ phenomenon. It was a disease that was concentrated among Haitians or intravenous drug users or clusters of unlucky gay guys out in San Francisco… [but] suddenly there was this notion that if Rock Hudson, the boy next door, can have Aids, anybody can have it.”

Arguably, Hudson’s death overshadowed his life. He became more famous for his Aids diagnosis than for the 30 years he’d spent as one of Hollywood’s most reliable and versatile stars. Griffin thinks he is ripe for rediscovery. “We hope to resurrect Rock Hudson, as it were, and have him remembered and recognised by a younger generation,” he says. He adds that most people under 30 don’t know anything about him, but believes that his story is both fascinating and inspirational. “Think about everything that Rock Hudson embodies as one individual – the American dream, the Hollywood star trip, gay life both pre- and post-Stonewall. And then he becomes the face of Aids. For one individual to embody all of that is pretty extraordinary. And that is somebody that needs to be remembered.”

‘Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed’ is available on digital platforms from 23 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks