Harry Potter hero, Sixties pop star, part-time barkeep: The storied life of Richard Harris

With a new feature documentary set to tell the tale of the late Irish star, Geoffrey Macnab casts a look back at the renowned actor’s inimitable career – and infamous antics

Taking a break from shooting a movie in the late Sixties, Richard Harris chartered a private plane. The actor and his entourage travelled to Hamburg to visit the brothels, and then went on a day trip to Ireland, spending an afternoon at one of Harris’s favourite pubs. They weren’t sober for a moment of the jaunt, which was chronicled by a photographer sent along for the ride.

The story of their antics is told in Adrian Sibley’s new feature documentary The Ghost of Richard Harris, a world premiere at the Venice Film Festival this week. What is most extraordinary about this particular episode is that it was nothing out of the ordinary for the Limerick-born star. Zigzagging across Europe in search of adventure, sex and alcohol was simply what Harris – at that stage of his life, at least – did.

His various paramours could likely attest to that. Sibley’s documentary alludes to a brief affair the actor may have had with Princess Margaret, a rumour he himself never confirmed. “Although Richard was a ‘swordsman’ in the Errol Flynn way, he was not somebody that I felt would be attacked by #MeToo. People may disapprove of his behaviour, but he was always quite gallant in his attitude toward women,” Sibley tells me. “I like the nobility of the fact that, although he had conquered the bastion of Windsor Castle by mounting the Queen’s sister, which I felt was like an Irishman planting a flag... he never revealed that.”

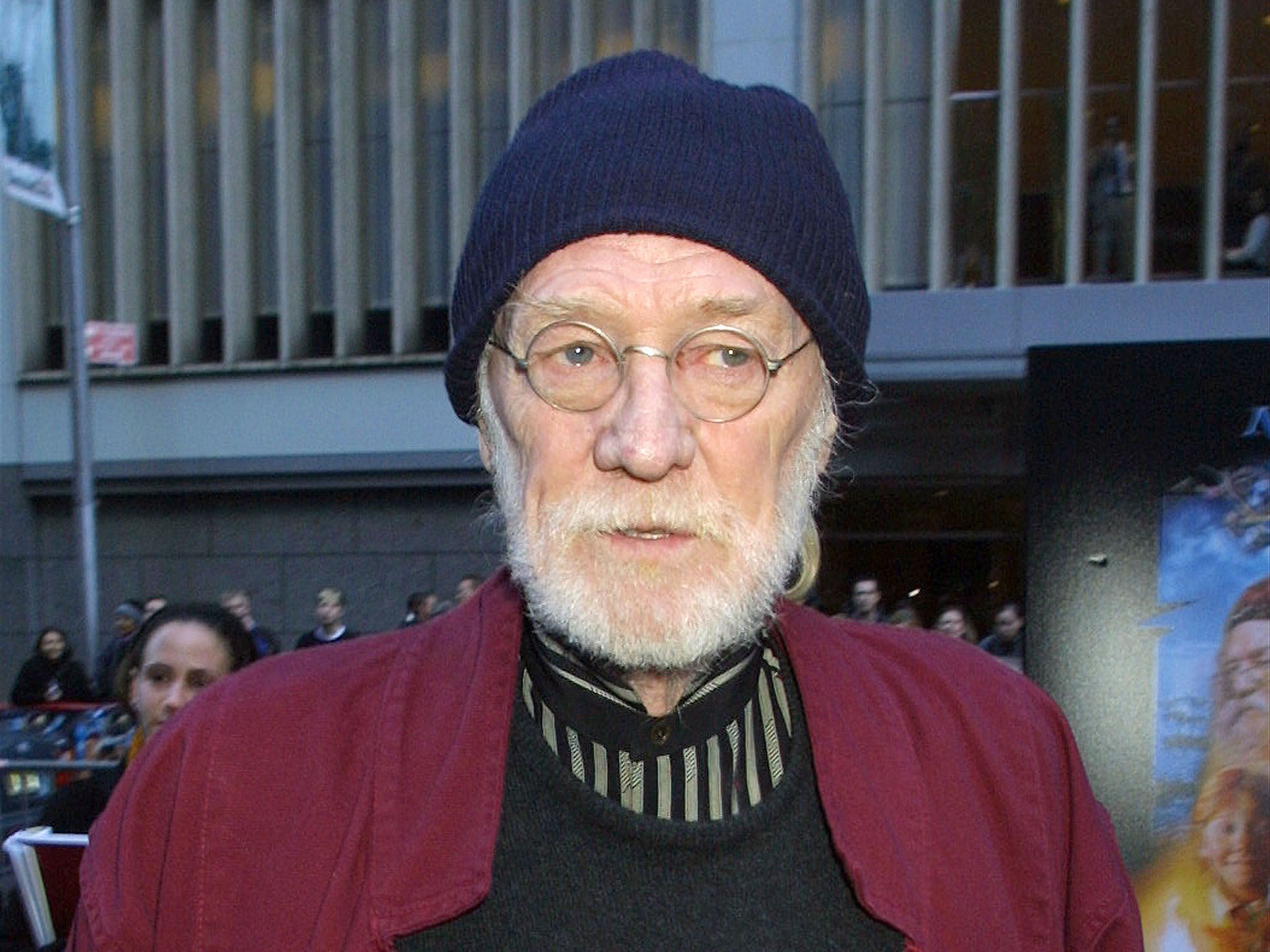

It’s a tantalising, if prurient, insight into Harris’s love life – but the story about Princess Margaret also underlines why contemporary audiences remain so confused about the actor, who died in 2002. There have been other films and books about Harris; Irish director Brian Reddin’s documentary A Man Called Harris (2020) and Michael Feeney Callan’s 2014 biography have both tried to unravel the mystery behind the man. But the question lingers: what did he stand for?

Younger audiences remember Harris best for two notable late screen performances – as Marcus Aurelius opposite Russell Crowe’s Maximus in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000), and as Dumbledore in the early Harry Potter films. You don’t immediately expect to see Harris in the wholesome world of Hogwarts, but his granddaughter loved the JK Rowling books, and Harris knew a blockbuster franchise when he saw it.

Others view him alongside Peter O’Toole, Richard Burton and Oliver Reed – one of that rogues’ gallery of jaded, once-brilliant Sixties movie stars who became fixtures in the gossip columns, as renowned for their boozing, brawling and bad behaviour as they were for their acting.

Harris had parallel careers as a pop crooner (enjoying a top 10 hit with the 1968 ballad “MacArthur Park”) and as a poet. At the height of his fame, he took a sabbatical from his screen acting duties to work as a bartender in his friend Malachy McCourt’s pub in New York. “Harris poured with abandon and without measure and never seemed to take money from any of the clientele,” McCourt writes in his memoirs.

The pub owner was appalled to hear from “a couple of cheery and quite inebriated elderly ladies” that the nice young bartender had refused payment for their bottle of Dom Perignon. Harris, though, kept count of all the free drinks he gave away and, when he quit the job, left McCourt with a cheque to cover them.

Such anecdotes make Harris seem slightly absurd – an Irish popinjay who didn’t take himself too seriously. Public funders in the UK, including the British Film Institute, refused to support The Ghost of Richard Harris because (Sibley believes) they felt the actor was “boorish and sexist”, a relic from another age. Those funders forget that there was a period early in his screen career when Harris, in the rawness and feral intensity of his acting, was the closest thing British cinema had to its own Marlon Brando.

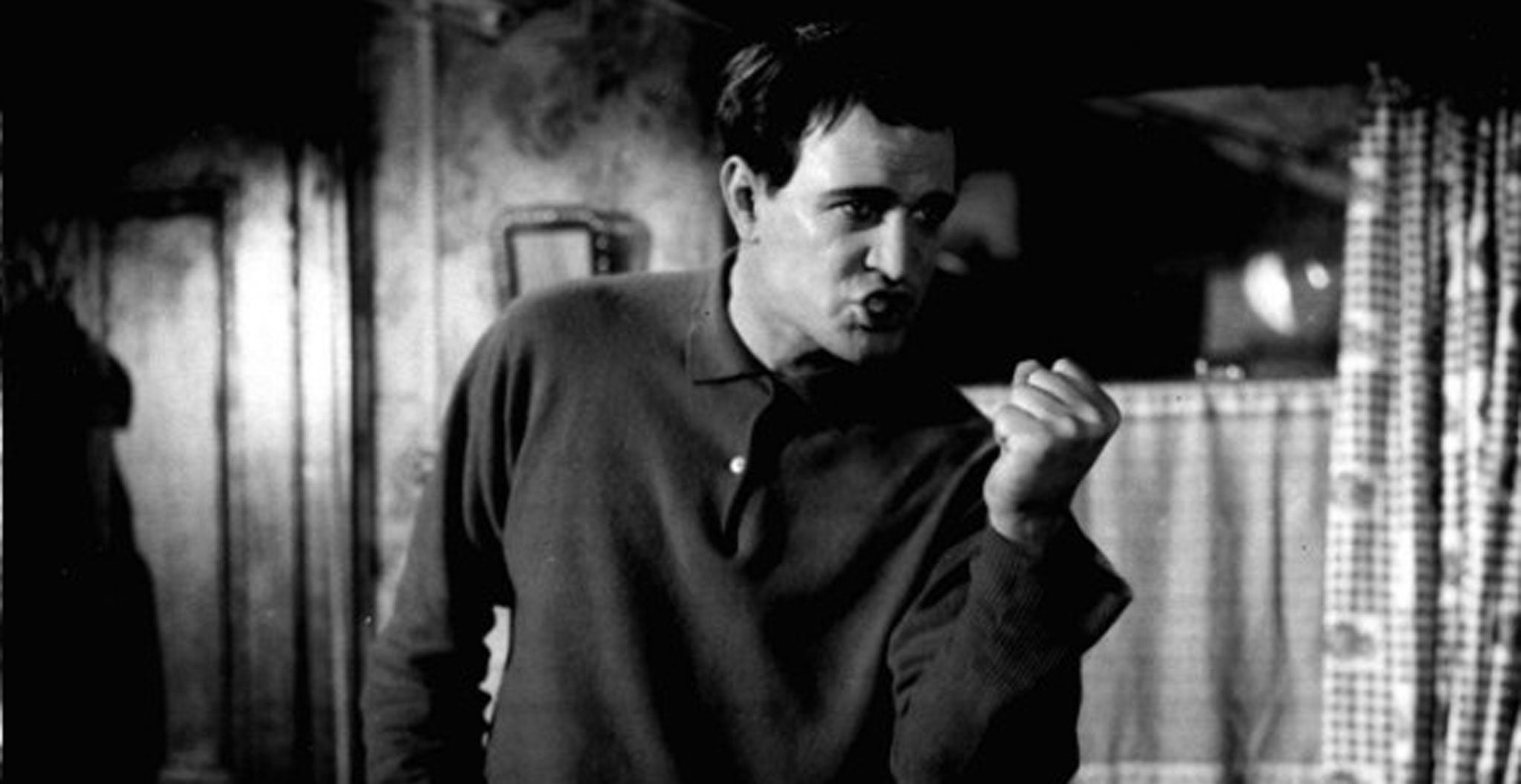

In a glowing Observer review of Lindsay Anderson’s 1963 film This Sporting Life, critic Penelope Gilliatt wrote: “I’ve never seen an English picture which gave such expression to the violence and capacity for pain that there is in the English character.” She called it a “stupendous” film that had “a blow like a fist”, and rhapsodised about Harris’s “magnificence”. There’s an obvious irony to her words, in that Harris was proudly Irish, but she was right. In the role that won him Best Actor at Cannes, Harris excelled.

He plays Rugby League professional Frank Machin, and gives a searing performance as the hulking, macho northerner ashamed of his soft and vulnerable side. In the film, Machin has an ill-starred, destructive affair with his landlady Mrs Hammond (Rachel Roberts). The real romance, however, flourished between the director Anderson and his star Harris, with whom he became obsessed.

“His mixture of tenderness and sympathy with violence and even cruelty is astonishing,” Anderson wrote of his leading man in his diaries. He later told film historian Brian McFarlane that Harris was “tremendously ambitious” but “also in many ways unconfident, which made him a difficult actor to handle but ideally cast”.

Growing up in Ireland, Harris had dreamt of playing rugby for his country. He was a promising young player, but any hopes of sporting glory were crushed when he caught tuberculosis as a boy and was confined to bed for months on end. It seems somewhat typical of the always contradictory actor that in his youth he was both an athlete and an invalid. Equally, he was very gregarious but spent long periods on his own.

He was angry and rebellious, and yet he came from a respectable middle-class background (part of a once-prosperous flour-milling family). He was the raging, chaotic chancer who became an absolute perfectionist when he believed in a project. He lived for his art and yet craved money and fame.

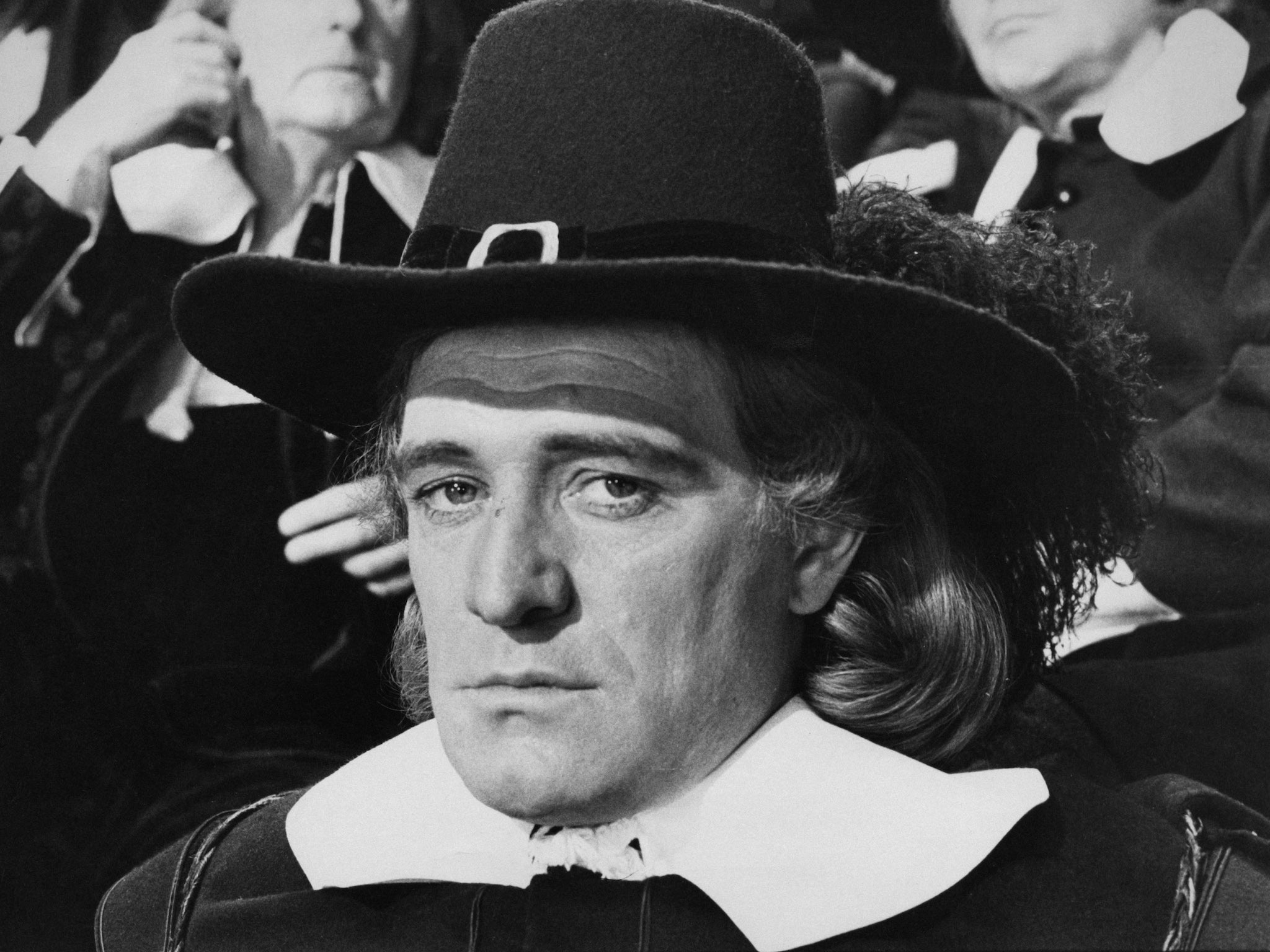

Harris espoused a romantic Irish nationalism, and supported the IRA before becoming alienated by the group’s violence, but that didn’t stop him from portraying Oliver Cromwell in sympathetic fashion in Ken Hughes’s 1970 biopic of the English soldier and politician, who remains one of the most loathed figures in Irish history.

In his early screen roles, Harris had both an intense physicality and a vulnerability. He was mercurial and intense in a way that other British actors of the period were not. (As he used to joke, he was considered “English” if he won awards, but “Irish” whenever he was arrested after a pub brawl.)

Harris may have made his name in kitchen sink dramas, and in arthouse films like Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Red Desert (1964), but with a young family to support, he soon headed to Hollywood to star in lucrative action movies and westerns like The Heroes of Telemark (1965) and Sam Peckinpah’s Major Dundee (1965).

Then came the musical hit Camelot (1967), in which he played King Arthur opposite Vanessa Redgrave’s Queen Guinevere. This brought him a level of mainstream success he would never have achieved in Europe. Bizarrely, he capitalised on his growing celebrity by reinventing himself as a pop star. “The pop scene isn’t a closed shop. Anyone can have a go. Besides, there’s no one around I rate apart from Tom Jones,” Harris bullishly told the Daily Mirror (28 December 1967), as he signed a contract to make six albums in three years.

Harris, though, was a mercurial figure with a tendency to fall out with even his closest collaborators. Jimmy Webb, the young songwriter behind “MacArthur Park”, was infuriated when Harris backtracked on a deal to hand over his Rolls-Royce Phantom V in the event that the song became a hit – which it did. Directors often grew exasperated by him. He drank too much and could be monstrously egotistical. He was also, as he once informed a journalist, an “exceedingly horny bastard”.

“F*** ’em all,” Harris responded when Feeney Callan, researching his biography, informed him of the hostility shown towards him by some of his old colleagues. He enjoyed riling them. The actor’s screen career is uneven in the extreme. There’s a lot of dross in there – long-forgotten TV movies, half-baked war pictures, and by-the-numbers thrillers. In the Eighties, Harris received a Golden Raspberry nod for his awful performance as Jane’s father in the equally awful Bo Derek version of Tarzan the Ape Man (1981), during the filming of which he shocked his co-stars by wandering naked around the jungle sets.

When given the chance, though, Harris was capable of astonishing work. Some of his best performances came late in his career, when detractors had already dismissed him as a has-been. He was superb in Clint Eastwood’s brutal western Unforgiven (1992). Harris played English Bob, the ageing and very dapper gunslinger living off past glories who is humiliated by the town sheriff (Gene Hackman).

It was a supporting role, but Harris brought the same rawness and masochism to the part that he found all those years ago as Frank Machin in This Sporting Life. He still excelled at portraying big men whose illusions and insecurities are laid bare.

Further redemption came in Jim Sheridan’s The Field (1990). Harris was only cast in the leading role after Ray McAnally, the actor originally chosen, died suddenly. Harris had to lobby hard for the part, and there was considerable scepticism that he could pull it off, but he never softened his approach. He was playing an awkward, stubborn character, and was determined to be as awkward and stubborn on set as possible.

Nonetheless, his performance as the grizzled old-timer Bull McCabe, eking out an existence in rural Ireland, secured him a Best Actor Oscar nomination. This was Harris in thunderous, full-blooded King Lear mode, and even Sheridan, wary about aspects of his leading man’s approach to the role, was ultimately very moved by him.

Twenty years after his death, Harris remains an object of fascination and bewilderment. Given everything, you might expect his story to end badly, but it doesn’t really. He didn’t die forgotten, or impoverished, or full of regret. But nor did he entirely fulfil himself. It would be a mistake, though, to think that he frittered away his career. The wildness and recklessness with which he approached life offscreen were precisely what made him such a magnetic presence in his best movie roles. He fed off his own braggadocio. As his fellow actor Joe Lynch told Feeney Callan: “He had such neck, you just forgave him everything.”

‘The Ghost of Richard Harris’ premieres at the Venice Film Festival on 4 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks