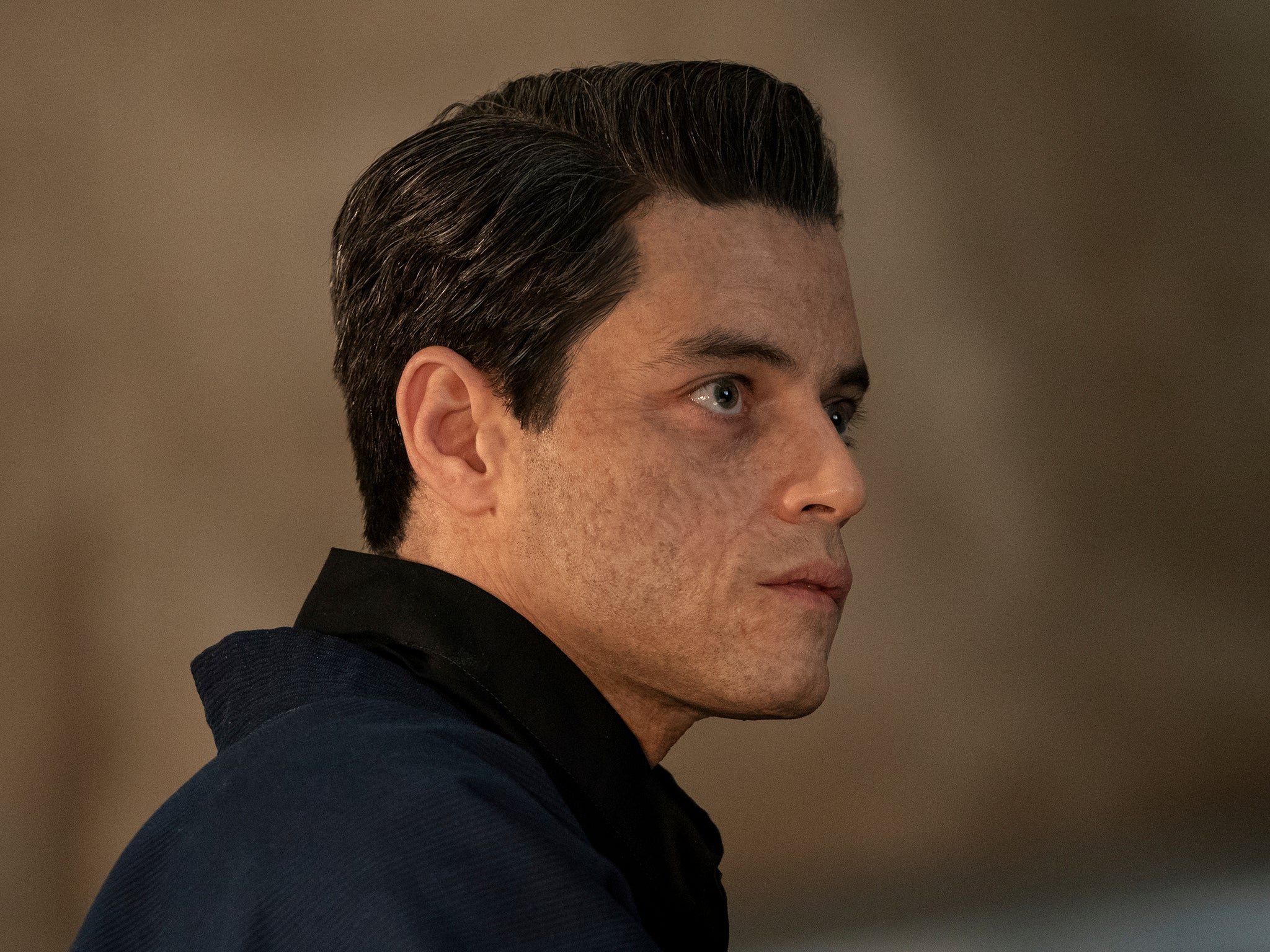

Can Rami Malek act? How the No Time to Die baddie became the most polarising actor in Hollywood

With the Oscar winner’s baffling performance in the new Bond film following equally strange turns in ‘The Little Things’ and ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’, Adam White asks: what’s happened to one of our most interesting character actors?

Rami Malek is our greatest extra-terrestrial actor. Unfortunately he’s a human being. For the last few years, he has been cinema’s go-to oddball, whether the roles themselves called for eccentricity or not.

In Bohemian Rhapsody, for which he won an Oscar, Malek played a pair of costume-shop teeth playing Freddie Mercury. Earlier this year, in the Denzel Washington thriller The Little Things, he was inexplicably weirder as a good-natured cop than the bedraggled serial killer he was pursuing (played by a slightly less weird Jared Leto). And this week, he is comfortably the most cringe-inducing aspect of the new James Bond film No Time to Die. It raises some important questions, the main one being: can Rami Malek act?

Well, he can. But to an extent. Malek is a polarising performer, an actor who injects a very specific barrel of otherworldly tics into his characters. Watching him is almost like seeing someone trying to crawl out of their own skin, every line a nervous whisper, his body language tense and anxious. He’s certainly intriguing and unique, but perhaps best consumed in short, sharp doses.

In No Time to Die, Malek plays 007’s latest nemesis: a vengeful killer who pontificates deviously from his island lair. The part is a compendium of Bond villain clichés, from his all-too-familiar plot for world domination to his facial scarring, but Malek’s performance doesn’t help matters. “Few actors could redeem a role this basic and Malek isn’t one of them,” wrote IndieWire in their review, which also criticised Malek’s “hodgepodge of an Eastern European accent” in the movie. He is “shorn of charisma and energy”, wrote Metro. “His specialty is muttering in an ominous monotone,” added Screen Daily. Malek is the film’s “lispingly clichéd weak link,” claim the Financial Times. And so on.

Malek’s slightly askew acting choices seem to stem from his process, which involves delivering “a slew of experimental takes before I get to one that might possibly [work]”. He explained that to Robert Downey Jr during a conversation with him for Interview Magazine in 2016 – when Malek was the star of the cult TV series Mr Robot – but by 2018 it seemed to have passed into his off-camera life, too. Much of a profile interview that year for The New York Times is taken up by descriptions of Malek’s erratic elasticity. “I had to ask why he had been so jumpy at the interview’s outset,” wrote journalist Cara Buckley. “He had twitched, hugged himself, crossed and uncrossed his legs, scratched his arms and jiggled at a terrific frequency that suggested advanced jitters or vast amounts of caffeine.”

Fame isn’t for everyone, and Malek has always seemed a bit like a character actor uncomfortably positioned as a leading man. But it’s especially strange to watch him go so big and broad in a new film when he used to be much more nuanced. Malek always stood out in his movies. It might have been because of his dark, baggy eyes, or the quiet elegance he imbued even his smallest of roles. Whatever the reason, he was never a lightning rod because he was particularly grating to watch. It’s different now, though. Somewhere along the line his acting seemed to shift, Malek abandoning much of the quietness of his earliest parts in the process.

Jump back a decade and Malek is marvellous as a well-intentioned but hopelessly naive rich kid in the indie hit Short Term 12. He also lingers ambiguously on the fringes of Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master as Philip Seymour Hoffman’s wide-eyed son-in-law, always watching, marvelling, planning something. Malek’s most significant scene in The Master doesn’t actually feature his face. His character is taking part in a ritual for Hoffman’s religious movement in which he barks demeaning “truths” to Joaquin Phoenix’s adrift war veteran. It’s a chilling moment, but for Malek it also seemed to be an instructive one.

The ungainly Malek performances of today seem cast in Phoenix’s sinewy, method-acting shadow. And it’s almost as if a ghoulish bit of transference occurred in their scene together in The Master, a spirit of Stanislavskian pretension passing from one Hollywood beanpole to another.

Whether Phoenix can get away with it himself is debatable – all method acting is on some level completely exhausting – but he’s at least had the foresight to spread his deeply committed limbs over good films. And Joker. He also seems to recognise that there’s a time and a place for everything. Phoenix goes big in films that call for a particular brand of nervous energy and loud physicality – think The Master, Inherent Vice or The Village – but is more than capable of dialling it down, too, in a Her or a You Were Never Really Here.

Malek, on the other hand, applies his idiosyncrasies to films that don’t really require them. The Little Things is the kind of sub-Se7en cops-and-killers movie that would have probably starred Ashley Judd 20 years ago and is not an obvious opportunity for method wildness. It’s distracting as a result. Bond villains, too, work best with a sliver of camp to them, be it Famke Janssen getting off by cracking men’s necks between her thighs in GoldenEye, or the slippery homoeroticism of Javier Bardem’s Skyfall bad guy. Malek seems to be trying to emulate Bardem in No Time to Die, but somewhat self-seriously. There’s no joy or carefully curated flamboyance – just misplaced gravity.

It all makes Malek a jarring movie star, someone slightly odd on-screen but no longer in a way that feels especially productive. And when you’re too over-the-top for a franchise that once featured a henchman with killer teeth made of solid steel, well, you know something’s gone terribly wrong.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks