How Martin Scorsese helped rescue Britain’s most important filmmakers from anonymity

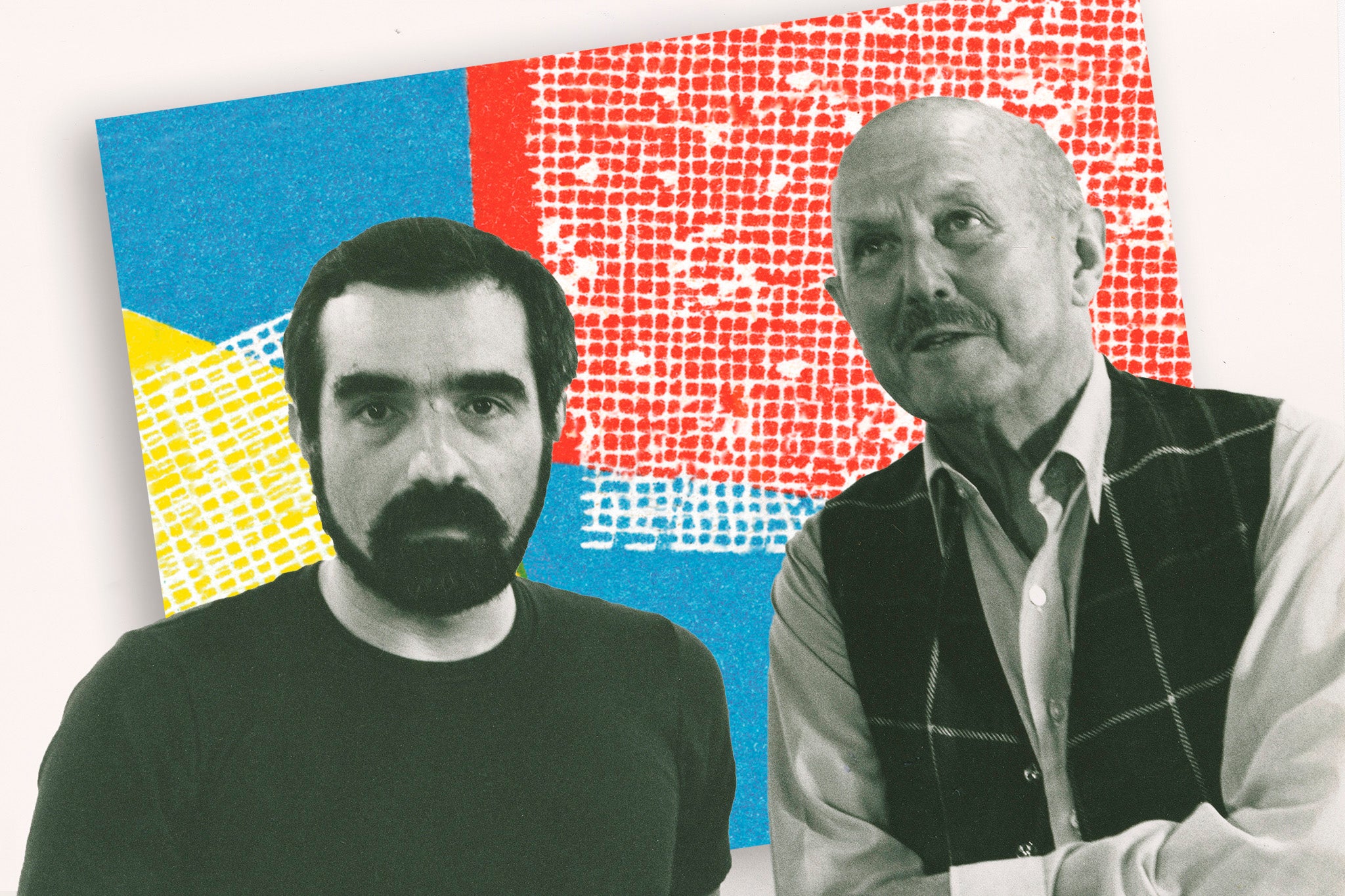

The legendary director’s long-time editor Thelma Schoonmaker speaks to James Mottram about their three-decade mission to restore the works of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger – visual geniuses whose Technicolor fantasias were once at risk of being forgotten

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For the past three decades, few have been more dedicated to preserving the legacy of British filmmakers Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger than Thelma Schoonmaker and Martin Scorsese. Schoonmaker, one of cinema’s most renowned editors, and Scorsese, for many the world’s greatest living director, have made it their business to ensure audiences remember the men behind such indelible movies as The Red Shoes, Black Narcissus and A Matter of Life and Death.

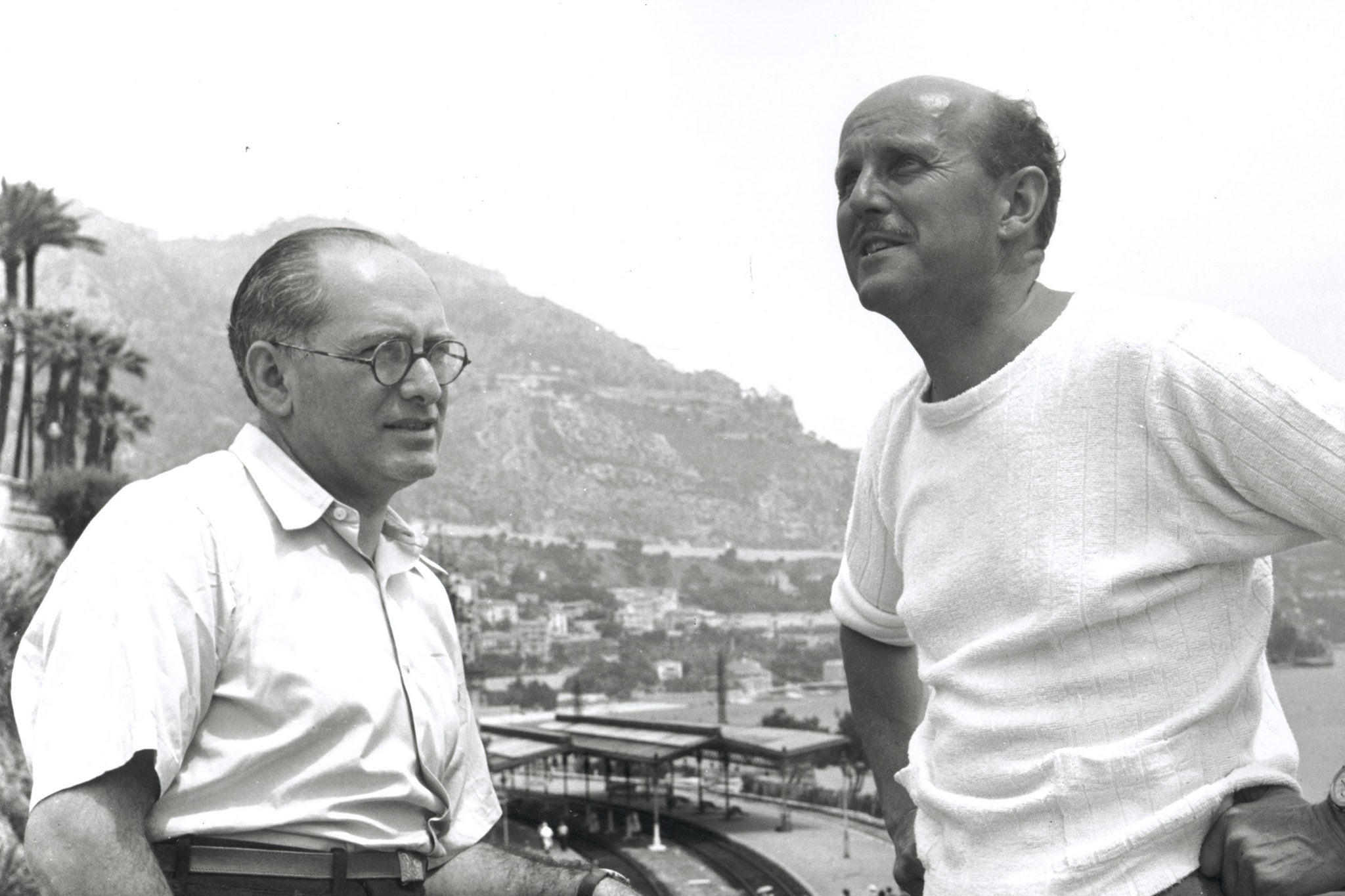

The pair – Powell died in 1990 at the age of 84, Pressburger in 1988 at the age of 85 – were cinematic fabulists, responsible for visually rich Technicolor fantasias, the likes of which have never been seen before or since. Schoonmaker and Scorsese have been a similar dream-team ever since their first collaboration on the 1980 boxing saga Raging Bull, for which Schoonmaker won an Oscar – her first of three, followed by wins for editing The Aviator (2004) and The Departed (2006). It was in the immediate aftermath of Raging Bull that Scorsese introduced Schoonmaker to Powell, who he’d befriended in the 1970s, after the British director had split from his Hungarian-born producer/screenwriter, Pressburger. They’d enjoyed success in the Forties and Fifties, but by the time Schoonmaker became a fan of their work, their names had fallen into obscurity.

“Nobody knew who they were anymore in England,” says the white-haired Schoonmaker, 84, when we meet in a Berlin hotel. “Marty got an award at the Edinburgh Film Festival for [his 1974 film] Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. And they said, ‘Who do you want to give you the award?’ He said, ‘Michael Powell’, and they said, ‘Who is that?’ They had no idea!” But Powell was located, and he and Scorsese struck up a bond. “The blood started to run in my veins again,” Powell wrote in his autobiography.

By 1984, Schoonmaker was married to Powell, who was 35 years her senior, while her own career as Scorsese’s go-to editor was flourishing. “I’m very lucky,” she reflects. “It’s the greatest job in the world. And [Scorsese] gave me the greatest husband in the world! So I’ve had it all.” Ever since Powell’s death in 1990, Schoonmaker and Scorsese have proudly overseen the restoration of his and Pressburger’s films. It is work that’s on-going: early June sees the re-release of one of their lesser-known titles, The Small Back Room, a 1949 British noir starring David Farrar.

This appreciation of their canon looks set to continue with Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger, an exhaustive documentary that sees Scorsese on camera guiding audiences through their entire career. Directing it is David Hinton, who first met Powell in the 1980s during filming of a South Bank Show special on the director. Sitting next to Schoonmaker, Hinton recalls Powell being “full of energy” when they first met, thanks to Scorsese’s friendship. “Since then, the Powell and Pressburger reputation has just gone from strength to strength. In a way, they keep being rediscovered again and again.”

Last autumn, the British Film Institute staged a two-month long season, “Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger”. “Every screening was packed with very young people,” adds Hinton. “I think there’s still new generations who are discovering the films.” But it will undoubtedly be Made in England that further cements Powell and Pressburger’s reputation. Schoonmaker calls their work “very pure… very emotional, particularly for a British film at that time”.

It’s lovely to be working with him, because he’s always changing, and never repeats himself. And we share this great love of Powell and Pressburger

Made in England is also a treat for Scorsese fans. The director is well-known for his cine-literate documentaries, like 1999’s My Voyage to Italy, in which he explored the movies – by the likes of Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio de Sica and Federico Fellini – that influenced his youth. Likewise, he discovered Powell and Pressburger as a young man, and talks passionately in Made in England about how their unique, flavoursome work influenced his own films – he even directly lifted shots from their work for Raging Bull and his 1993 Edith Wharton adaptation The Age of Innocence.

“These films were not like the ones he’d been seeing from Hollywood,” says Schoonmaker. “They didn’t have real villains and real heroes. They were more about people. More like us. And [Scorsese] liked that very much, because that was in his instincts. I think he was born to be a film director. He came out of the womb that way. And so he was instantly drawn to these movies.” Whenever he saw the logo for their production company, The Archers, depicting an arrow hitting its target, “he knew it was going to be something unusual”.

As fascinating and informative as it is to hear Scorsese wax lyrical about their films, the real meat comes as we learn about his friendship with Powell. There is some touching footage of the British filmmaker on the set of Scorsese’s The King of Comedy, his masterly 1982 tale with Robert De Niro and Jerry Lewis. Powell’s previous film – which would turn out to be his last – had been a decade before, 1972’s The Boy Who Turned Yellow. “He went through a very hard 20 years of total oblivion, unable to make a movie but writing and writing and writing wonderful ideas,” says Schoonmaker.

Several times, Scorsese tried to help Powell get projects underway. “Michael was very impatient with people. He would just insult them,” chuckles Schoonmaker. “But Marty, growing up in a mafia neighbourhood and working in his early days in Hollywood, learned how to deal with people of power and how to raise money from them, even though they disagreed with what he was going to do. He had that technique. But Michael didn’t need it. Because in the war years, they were just making masterpiece after masterpiece.”

Films like wartime sagas The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp and A Canterbury Tale were warmly embraced but, as Schoonmaker points out, it was during the production of 1948’s The Red Shoes that “trouble started”. Set in the world of professional ballet, and starring Moira Shearer as an aspiring dancer, the film was a profitable, Oscar-nominated success and remains heralded for its timeless, magical qualities. Yet its backers, the Rank Organisation, “didn’t understand it”, putting a huge strain on the company’s relationship with Powell and Pressburger, ultimately leading to a parting of the ways.

Subsequently, the success of their films dwindled and The Archers fizzled out, although Powell was not done. Separate from Pressburger he created one of his most notorious films, Peeping Tom (1960), a highly disturbing psychodrama about voyeurism. It was, however, critically reviled upon release. Was it Powell’s biggest heartbreak? “The thing about Michael is that he always believed that what he was doing was right,” Schoonmaker muses. “And so even as painful as it was, as destructive as it was… he never gave up knowing he was right. But it was hard.”

Born in Algiers, Schoonmaker didn’t encounter Powell’s work until her teens. Her father Bertram worked for the Standard Oil Company, and her early years were spent on the Caribbean island of Aruba. She didn’t really see television until her family moved back to the States in her mid-teens. “One of the first films I saw was The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp,” she remembers. “And it just was seared into my mind for some reason.” She speaks fondly of the moment Roger Livesey’s Lieutenant Candy realises he has feelings for Deborah Kerr’s Edith. “I just think it’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen.”

By the time Peeping Tom was released, Schoonmaker was at Cornell University studying Russian and political science. She began to pass State Department tests to find a position in the US government, until she was questioned “very strongly” about apartheid by representatives from the FBI, CIA and the State Department. They asked her what she would say about the system if she were in South Africa. “And I said, ‘Well, it has to end. It’s terrible.’ And they said, ‘Well, you can’t do that, as a diplomat, until your country decides to do that’.”

Looking for another vocation, Schoonmaker secured a job as a trainee assistant editor, and later met the young Scorsese, famously joining him on the editorial team of Michael Wadleigh’s 1970 music documentary Woodstock (for which she was nominated for her first Oscar). They stayed in touch through the Seventies, but it wasn’t until Raging Bull that they officially worked together again. The film cast De Niro as real-life boxer Jake LaMotta, and it was Schoonmaker’s baptism by fire. “I learned so much on Raging Bull,” she says. “I mean, [Scorsese] was teaching me.”

Did they ever have disagreements? “We have never really disagreed firmly, I don’t think, and the most important time was at the end of Raging Bull where De Niro is facing himself in the mirror. And they did 15 takes, which is highly unusual. They were talking back and forth between each other with each one, ‘Should we go that way? Should we go this way?’ I liked the warmer takes. Scorsese said, ‘No, he has to be cold.’ And so we screened with our friends two ways. And Marty was right!”

Rarely working for other directors, Schoonmaker has remained loyally by Scorsese’s side, right up to last year’s Killers of the Flower Moon, which earned her a ninth Oscar nomination. “It’s lovely to be working with him, because he’s always changing, and never repeats himself,” she says. “And we share this great love of Powell and Pressburger, which is something we talk about all the time.” And now, with Made in England, The Archers will be hitting the bullseye once again.

‘Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger’ is in cinemas from 10 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments