Porn, Snapchat and teenage love: The new film exploring the sex lives of young millennials

‘Meaningless’ sex was once considered transgressive. But as Bang Gang: A Modern Love Story' shows, in the age of the smartphones and social media even normal children think it’s the norm

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

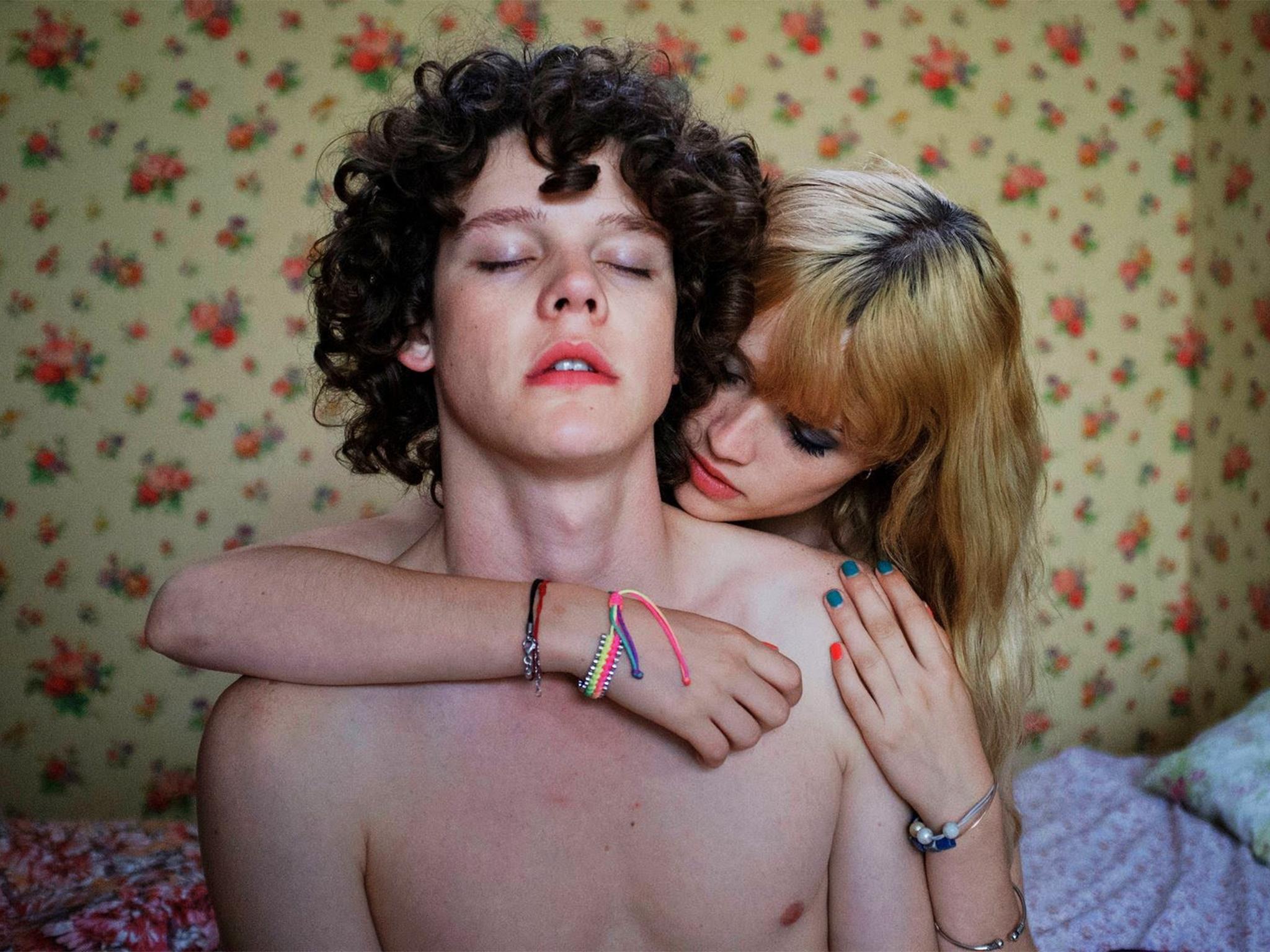

Your support makes all the difference.Alex, 17, is carefully thumbing his iPhone. He is naked, reclining on a chair. He looks up to see a willowy schoolmate, George(tte), staring tearfully at him. Without a blink he looks back at his phone, while another schoolmate continues to give him fellatio. George and Alex had sex a few days previously, but shortly afterwards Alex began turning the regular gatherings at his large house – his divorced parents are rarely there – into orgies, and any intimacy with George has subsided into a frenzy of plenty, much of it filmed.

This is a scene from Bang Gang: A Modern Love Story, a recent French film festival entry (nominations at Toronto, London and Les Arcs) written and directed by Eva Husson. It’s unlikely to reach a big audience, but it skewers some deeply contemporary concerns about youth in an unusually forthright way.

The focus on callous, competitive sex washed of physical consequences among bored, middle class teens is its most classic theme; think Brett Easton Ellis’s The Rules of Attraction(1987; film 2002), Donna Tartt’s The Secret History (1995) and Cruel Intentions (1999). Yet unlike those, Bang Gang – despite its brutal title – lacks a jet black core. Neither murder nor violence, nor even any very advanced subterfuge lurk; the kids all seem basically polite and decent; helping their parents out, obeying their commands. But the conceit of sexually exploratory, relatively privileged teenagers is the necessary backdrop for the film’s other, more urgent contemporary themes.

The first is porn; ubiquitous porn. Porn is both part of daily life for many teens and something easily made and disseminated to suit various purposes. This is the generation that hits puberty with a world of online smut at its fingertips: a 2015 report found that 39 per cent of boys aged 14-17 in the UK regularly watch it. It’s no surprise, then, that when the bang gangers get together for their orgies, the idea of filming and posting the sex occurs immediately.

Their well-to-do milieu is relevant here: a 2015 Pew report on teens and social media found that, the higher income of the tenn’s the family, the more interested in video circulation apps (such as Snapchat) they are compared to lower income kids, who prefer Facebook. The teens here opt for a password protected video feed for a select group – but it’s not made apparent whether ethical issues about posting their schoolmates mid-coitus on YouTube stop Alex and Nikita from doing so. As Alex and his horny crony Nikita muse, simply posting DIY porn at large on the internet is old hat. Ten years on from the invention of YouTube, it’s all about the social network.

We’ve all seen how habitual a part of daily life smartphones have become for everyone; the hush on rush-hour rail journeys is one obvious signal of widespread absorption. And sexting, which has been plaguing teens since smartphone ownership became commonplace, is also widely acknowledged.

But we are less au fait with the prominence of phones in sex simply as now-standard satisfiers of the compulsive itch to record and pose. Thus by far the most striking element of the sexual scenes in Bang Gang is the commanding part played by phones. With highly convincing naturalism, the actors use their phones as extra limbs. As they wrap their bodies around each other, a phone looms above, peering down, attached to a skinny arm. Sex, like much else in their worlds, is seen and felt through the iPhone camera. Teens of the 1980s may have got out the VHS recorder, but the effort and inflexibility involved was a deterrent, not to mention a turn-off.

For the viewer of 2016, identifying which desire is stronger among the teens – to have sex or to film the having of sex – is impossible. Nor is the filmic impulse masculine, perhaps signalling the arrival of some kind of sexual parity in a generation entirely raised on the internet and for whom active female sexuality is expected and apparently unremarkable (such attitudes, of course vary from country to country). It is George’s friend Laetitia, an initially withdrawn girl, who discovers a particular taste for voyeurism and often holds the camera.

Filming sex, however carefully, is not without risks. Someone breaks the code of honour and posts a copulating George on YouTube, but when her admirer Gabriel threatens him, it’s taken down. This is the perfect, isolated moment of chivalry in this modern love story, once more reinforcing the impression that the phone is the pole around which all aspects of sexual life increasingly revolve, both bearing witness and shaming. But as Gabriel’s move makes clear, while the phone is an all-powerful tool, and the internet has its own inexorable logic, human agency and responsibility are still where the buck stops. And that is where romance still lies.

The film also manages to pinpoint another issue of hot contemporary status. Has sex lost its meaning by becoming too easy, and too normal? This question has been brought sensationally to bear on a series of recent high-profile investigations of modern romance.

But the question may be just as epidemiological as social. With anti-retrovirals and drugs to check the progression of HIV, and the most other STDs easily curable (or preventable, in the case of the HPV vaccine), do contemporary Western teenagers feel any checks at all on the consumption of unprotected intimacy? Unable to find a condom when he takes Laetitia’s virginity, Alex tells her: “Don’t worry, we’re not a high-risk population.” Laetitia takes this with her trademark insouciance and on they go, the terror of the 1980s long forgotten.

Yet the orgies come to an end when George – Alex’s equal for prolific sexual activity – leaves chemistry class because of pain in her lower regions. Casually telling the nurse about the “bang gang” triggers a class-wide STD test, with diagnosis of syphilis for Alex, George and Laetitia, and gonorrhoea for Gabriel. Laetitia is also pregnant. The parties dissolve along with school for the summer, and as Laetitia leaves town with her father, she reflects via voiceover that “a shot of pencillin and, bam, no more syphilis; a pill, and bam, no more baby”.

With no consequences, and no restraints, does intimacy become not only casual but, in Gabriel’s father’s words, “mediocre”? Sex, like anything in abundance, shorn of barriers to entry, must lose some of its potency. Yet, quite apart from physical pleasure, its symbolic load and potential to provide validation tricks the brain into thinking more is more. Certainly from the perspective of an older person who came of age amid the politicised sexual activism of the 1960s and 1970s, this sexual tunnel vision might seem a paltry, inward-looking species of rebellion. “Some kids fight for revolution: you fight to fuck anything that moves?” asks Gabriel’s father.

He’s partly right and partly wrong. For these teenagers are not fighting. They’re taking. And the pleasure at the other end of it all remains just as, if not more, elusive than of old.

This article was first published on The Conversation (theconversation.com). Zoe Strimpel is a doctoral researcher in history at the University of Sussex

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments