Inside the real-life curse behind one of the world’s scariest movies

‘Poltergeist’ was inspired by a true haunting of a suburban home, but Annabel Nugent discovers it was also beset by terrifying behind-the-scenes chaos, both during and after filming. Here, she asks, was it all a morbid coincidence or was something scarier at work?

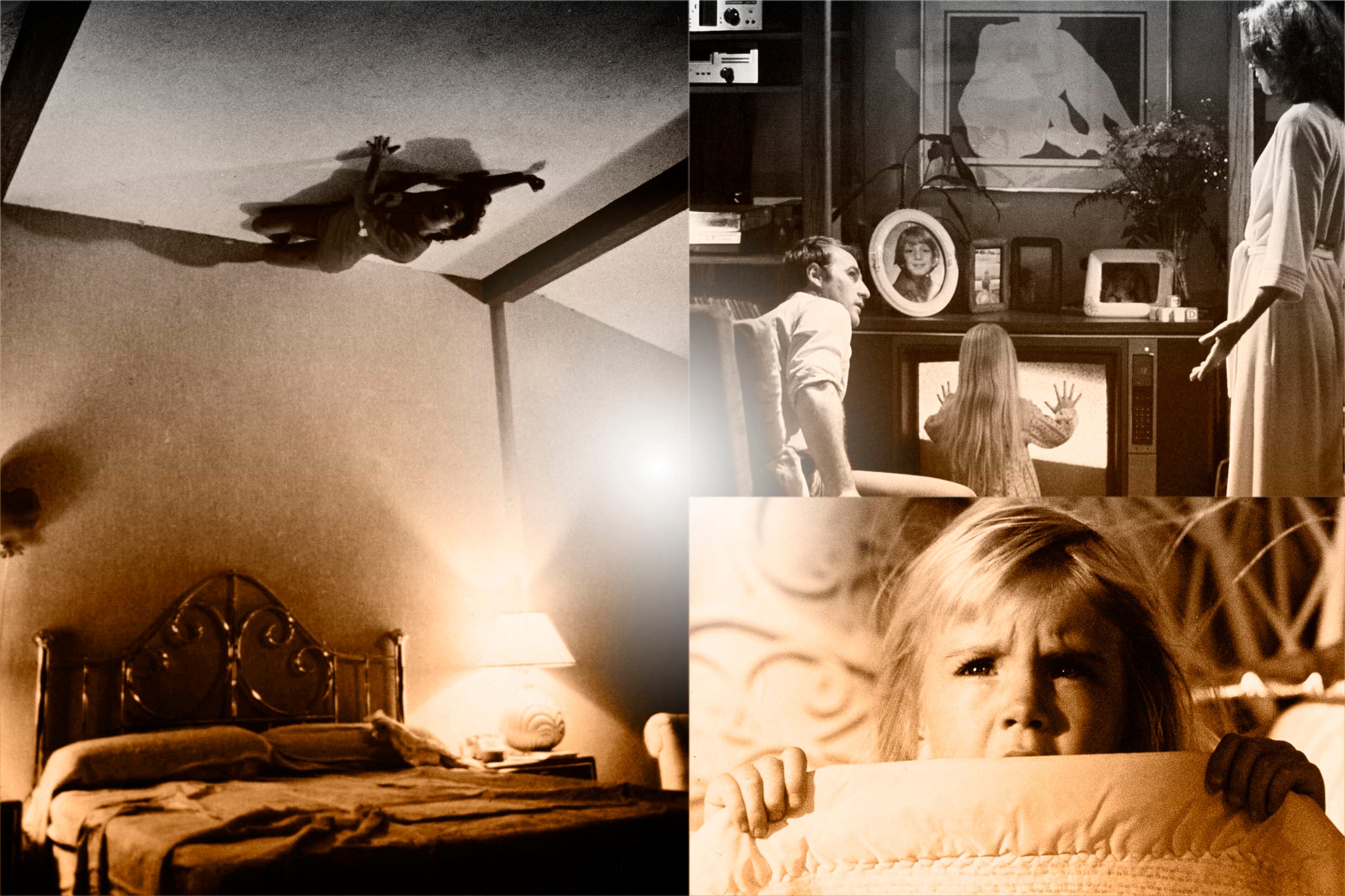

Over four decades since its release, Poltergeist remains a Halloween go-to. Come spooky season, horror devotees in search of sure-fire scares inevitably reach for Tobe Hooper’s movie about a picture-perfect family tormented by malevolent spirits. Between the swimming pool of skeletons, a cackling clown doll, and a portal in the closet, there are plenty of frights to go around. Dodgy CGI notwithstanding.

Off camera, though, murder and illness led to real-life deaths far scarier than anything seen on screen – and before the cameras even began rolling, tensions were reportedly running high.

The nature of Hooper’s involvement in the film has been debated since its 1982 release. Many have claimed that Steven Spielberg had a hand in directing the movie that his official credits – as co-writer and co-producer – don’t account for. While the question of directorial authorship is yet to be answered (after the film’s release, Spielberg published an open letter publicly crediting Hooper for his work and thanking him for his “openness”), such reports of a power struggle on set only fed rumours of the film’s gruelling production, which involved accidents, tragic cast deaths and the use of actual human remains. The fact Spielberg apparently based his harrowing story on real-life events did not help to dispel rumours of a so-called curse on the film.

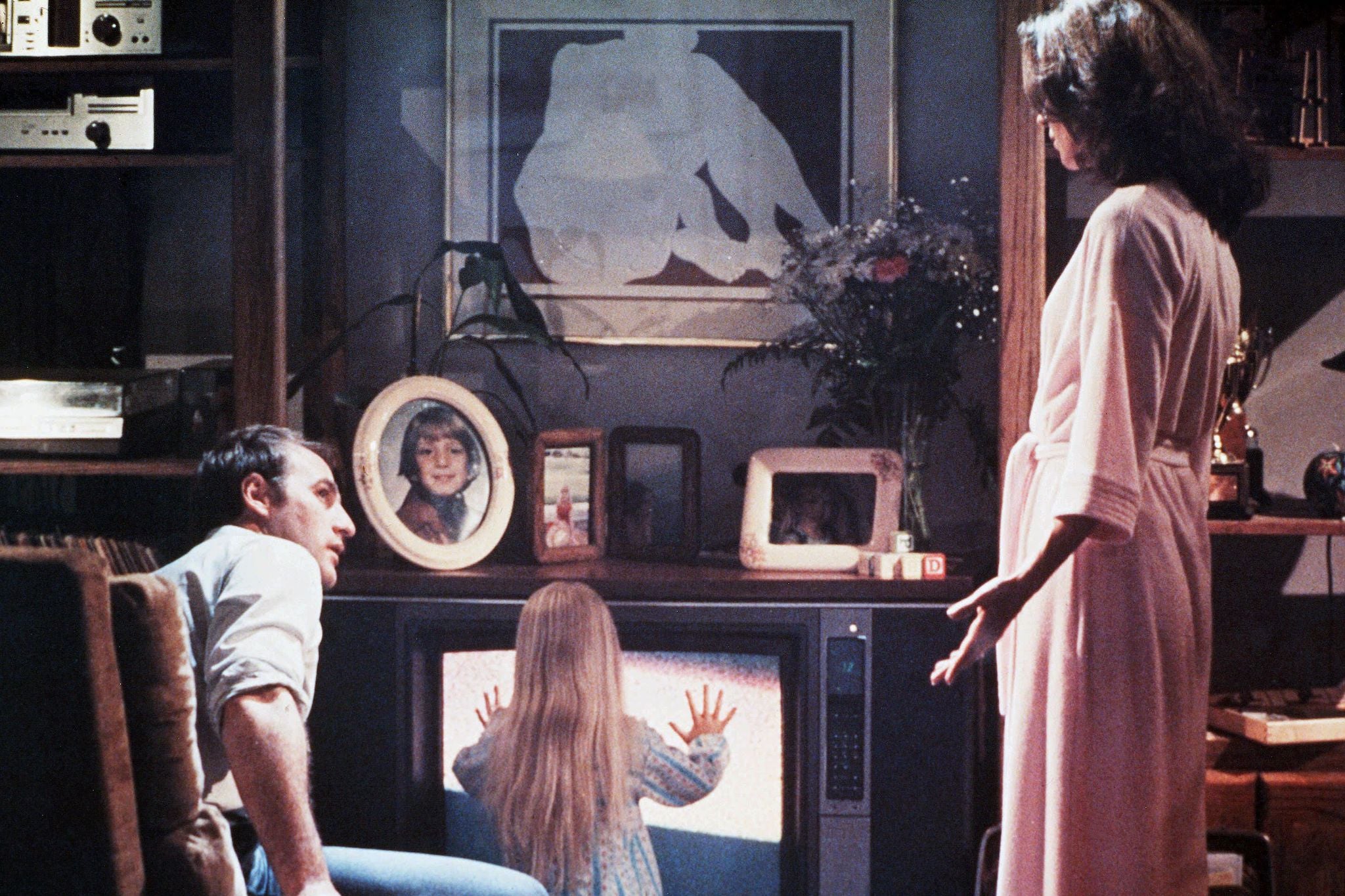

Poltergeist stars JoBeth Williams and Craig T Nelson as the Freelings, a happily married couple who, with their cookie-cutter home and cutie-pie children, are the picture of all-American suburbia. The dream is punctured, however, when chairs begin moving of their own accord and their youngest (the angelic Carol Anne, played by five-year-old Heather O’Rourke) starts chatting with the invisible “TV people”. Chaos ensues, and the furniture goes flying. Spielberg’s story was praised for its originality, but he didn’t come up with it alone.

It isn’t hard to see the parallels between the Freelings and the Hermanns, a Long Island couple whose own run-in with the paranormal was documented in a 1958 Life magazine article titled “House of Flying Objects”. The extraordinary occurrences, the article begins, started at 3.30pm on a Monday in February 1958 at the home of Mr and Mrs James M Hermann at 1648 Redwood Path. It had been an ordinary afternoon until “a number of bottles containing various liquids in various rooms of the house suddenly began to ‘pop’ and jump about”. These bottles were not that way inclined; these were screw tops that required two or three twists to come loose. Among those to “pop” was a container of holy water that sat on the bedroom bureau upstairs. Like the Freelings of Poltergeist – who initially delight in their home’s freaky oddity – the Hermanns were not so much frightened than they were amazed.

The incidents grew more frequent and more violent from there, though, with sugar bowls and 18-inch statues of the Virgin Mary soon flying off surfaces. One month later, items as heavy as a bookcase and a writing desk toppled over, the latter in 12-year-old James’s bedroom. The Hermanns called the police; a patrolman was sent to the home and he witnessed the disturbances first hand. As did Detective Joseph Tozzi, a “shrewd” man who, despite not believing in the supernatural, was unable to turn up any other explanation in the months of investigation that followed.

News of the flying objects travelled. Before long, the Hermanns were inundated with letters and phone calls from strangers hoping to solve the enigma: was it a downdraft in the chimney? A sonic boom from a passing aircraft? The result of streams running beneath their property? Radio waves? Or underground vibrations? Every hypothesis was looked into, and promptly disproved. Among the more left-field suggestions raised was the possibility of a poltergeist infestation. By its nature, this was one of the few theories that actually held up. (Unlike Poltergeist, however, the Hermann home was not, as far as anyone knew, built on a desecrated cemetery.) Still, the mystery stands, immortalised in print – and on screen.

Much less mysterious are the problems and tragedies that plagued the production of Poltergeist. Surrounding the film’s release were reports of eerie happenings and supernatural sightings on the film’s set. Admittedly, the alleged use of actual human skeletons in place of props did little to help dispel that notion.

One of the film’s most memorable scenes sees Williams’s character slipping into a swimming pool of mud amid a storm. To her horror – and that of the viewers – several skeletons bob about in the brown sludge as she tries to escape. It was only later that Williams learnt that the skeletons were real. “I assumed that they were prop skeletons made out of plastic or rubber,” Williams said in a 2006 episode of TV Land’s TV Myths and Legends. “I found out, as did the crew, that they were using real skeletons because it’s far too expensive to make fake skeletons out of rubber.” Her comments were never verified but the claims were never disputed.

Gross? Certainly. Supernatural? Probably not – although that didn’t stop others from fuelling the rumours themselves. In a 2010 interview, Hooper was asked whether it was “scientifically proven” that there was not a ghost on set, to which the director offered a mysterious: “No…” In the same interview, he ominously added: “No one was killed in the making of the film, but something happened to everyone.” Reading retrospective cast interviews, though, it seems the injuries Hooper spoke of are less likely the result of a demonic spectre than they are the result of a haphazard film set in the Eighties.

One of the most punishing scenes for Williams to shoot saw her character tossed around the walls of her bedroom by invisible forces. To achieve the upside-down effect, a replica of the room was built on a colossal gimbal that rotated. Williams, at the full whim of gravity, violently rebounded and rolled off its walls. Speaking to Vanity Fair last year for the film’s 40th anniversary, Williams said: “Let’s just say the charm wore off after about 12 takes.” Recalling how the crew had explained the mechanics behind the 360-degree turning set, she added: “What they didn’t say was that I’d be doing 50 takes of it and by the end, my elbows and knees were bleeding.” The cameraman who was strapped in threw up multiple times.

What they didn’t say was that I’d be doing 50 takes of it and by the end, my elbows and knees were bleeding

Neither Williams nor Nelson said they felt any supernatural presence on set. Both actors did, however, express discomfort with the seemingly hazardous nature of filming, including the electrocution risks of that aforementioned pool of corpses. “It was of course surrounded by lights and surrounded by giant fans called Ritters, which are about 16 feet in diameter,” Williams told Vanity Fair. “When I first had to get into the pool, I was very scared because I’m nervous about electricity and water. And I just had this image of one of those fans or the lights falling into it and being electrocuted. I told Steven that I was scared to do it and he said, ‘I’ll tell you what, I’ll get in with you.’ He put on waders, and he said, ‘First of all, it’s all grounded, so it couldn’t electrocute you.’” Spielberg, in his waders, stayed with Williams in the pool for her first few takes. “I thought that was very sweet of him,” she said later.

It is true that Poltergeist suffered two cast deaths, though both occurred after its release. Still, it is difficult not to watch the film without thinking about the tragic ends of Heather O’Rourke, who was five during production, and Dominique Dunne, who was 22 when she portrayed Dana, the Freeling’s teenage daughter. O’Rourke, who went on to appear in Poltergeist II in 1986 and Poltergeist III in 1988, died aged 12 – the latter film was released posthumously. She suffered two cardiac arrests as a result of a congenital intestinal abnormality, which had been misdiagnosed as Crohn’s disease the year before. Her mother later sued the doctors, and the lawsuit was settled out of court.

In similarly tragic circumstances, Dunne was strangled in her driveway by her ex-boyfriend John Sweeney only months after Poltergeist was released. In 1983, to the dismay of Dunne’s family, Sweeney was acquitted of second-degree murder and convicted on the lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter.

Whether the result of a marketing ploy or an overly eager audience hoping to will fiction into reality for an enhanced viewing experience, rumours of a quote-unquote cursed set almost always swirl around horror movies. Truthfully, though, Poltergeist never needed anything beyond its 108 minutes to successfully scare us. It’s frightening enough as it is.

‘Poltergeist’ is available to watch on BBC iPlayer

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks