The Patsys: Diva dogs, Ronald Reagan’s chimp and the surreal history of ‘the animal Oscars’

Decades ago, a now-defunct awards ceremony handed trophies to superstars such as Audrey Hepburn’s cat in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ and the hero of the Francis the Talking Mule franchise. As the canine star of ‘Anatomy of a Fall’ becomes the darling of this current Oscar season, Clarisse Loughrey digs into one of Hollywood’s stranger tales of industry back-patting

There’s one Oscar snub this year that’s been wildly overlooked: Messi, the well-trained border collie of Justine Triet’s courtroom drama Anatomy of a Fall. Messi plays Snoop, the guide dog of Sandra’s (Sandra Hüller) visually impaired son, Daniel (Milo Machado-Graner), and a pivotal part of the film’s twists and turns. In short, the role requires some real canine acting chops, and Messi sells Snoop as the perky-eared and eternally faithful companion.

Of course, no animal has ever won an Academy Award, though legend goes that doggie superstar Rin Tin Tin – of forgotten hits A Dog of the Regiment and Jaws of Steel – technically received the most votes to win the very first Oscar for Best Actor in 1929. But the bitter, jealous humans of the Academy conspired against him – and the statuette was instead handed over to the bipedal, distinctly furless Emil Jannings.

Instead, Rin Tin Tin and other stars like him had to make do with a little-known animal equivalent to the Academy Award, known as the Patsy (or Picture Animal Top Star of the Year). In 1939, after a horse fell 70 feet and died on the set of Henry King’s Jesse James, the American Humane Association created its film and television unit, which still monitors the treatment of animals in productions today – they’re behind the “no animals were harmed” disclaimer regularly featured in film credits. They also established the Patsy Awards, which were divided into four categories: canine, equine, wild, and special.

Future president Ronald Reagan, then an actor, hosted the first Patsys in 1951, where Jimmy Stewart handed the top prize to Molly, who starred as Francis the Talking Mule in a popular series of seven films. A thread was fed into the animal’s mouth to force her lips to twitch, which was then dubbed over with Chill Wills’s deep, rough-textured voice. It was a simple but effective trick, for a period in which animal comedies made for reliable, straightforward family entertainment.

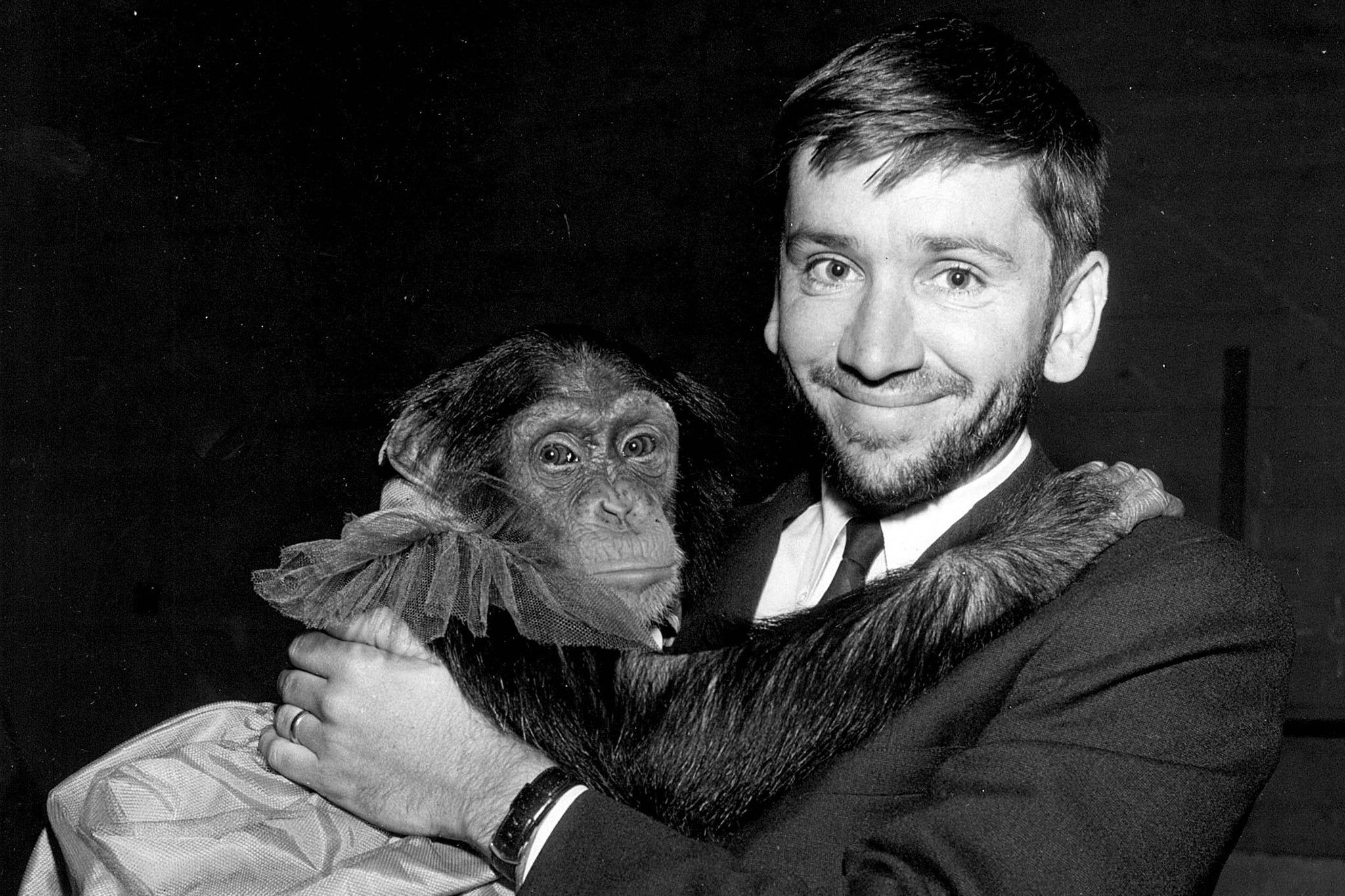

Reagan was fresh from Bedtime for Bonzo, a slapstick comedy which co-starred Peggy the chimpanzee, who was trained to obey 502 oral commands – she could cry, snarl, ride a tricycle, and open doors. “I fought a losing battle with a scene-stealer with a built-in edge: he was a chimpanzee!” Reagan would later joke. Tragically, Peggy could not be awarded during the inaugural Patsys, as the compound she lived in burned down shortly before the ceremony – she died of smoke inhalation, aged just six.

Other animals were more fortunate. In 1958, the award went to Pyewacket, the Siamese cat who served as Kim Novak’s familiar in Bell, Book and Candle, a romantic comedy about a witch who falls in love with a mortal. Supposedly, the actress fell so deeply in love with her feline co-star that the production actually gave her Pyewacket (either the real cat’s name was never revealed, or it shared its character’s moniker) once filming had wrapped. One of the most famous Patsy recipients, Orangey the cat, actually won twice: first, for his debut in 1951’s Rhubarb, about a feline who inherits a baseball team, and second for 1961’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, where he played the nameless stray who befriends Audrey Hepburn’s Holly Golightly.

Orangey was once branded “the world’s meanest cat” by a studio executive. He could, if he wanted to, happily stay in place for several hours. But he also loved to bite and scratch his co-stars and would slip away so frequently from set that guard dogs had to be stationed at the studio gates. He’d continue to work throughout the Sixties, even appearing as an accomplice to Eartha Kitt’s Catwoman in the Batman television show. He would eventually be buried next to Frank Inn, his trainer, at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in the Hollywood Hills.

A 1973 edition of Animal Cavalcade, a magazine published by The Animal Health Foundation, describes the first nationally broadcast edition of the Patsys, hosted by Betty White and Allen Ludden, and attended by the now-retired star of Lassie. Ben the rat won for the second, consecutive time, having starred in the rodent-based horror Willard and its sequel. Many of the show’s winners are still commemorated outside the Burbank Animal Shelter, their paws and hooves imprinted into the concrete in their very own Animal Walk of Fame. The Patsy Awards eventually came to an end in 1986, due to a lack of funds. And, with the mid-budget, family film now almost entirely replaced by superhero and animated franchises, there’s almost nothing today that can equate to Rhubarb or Bedtime for Bonzo. The era of the animal A-lister is now long gone.

That may, though, be a good thing. At the height of the Patsys – in 1975 – an investigation by The Humane Society News discovered that one trainer, with 40 Patsys under their belt, was keeping their animals under horrific conditions. Cages were packed with 30 or 40 cats, while a sea lion was discovered “living in a cage so small it could hardly move”. All of this wasn’t necessarily a product of its time, though – the question of welfare still lingers on today, as animal rights organisations like Peta and ALDF (Animal Legal Defence Fund) push Hollywood to replace real animals with CGI wherever possible.

Ridley Scott’s Gladiator 2 recently came under fire from Peta, who claimed to have received “whistleblower reports” that the production was “exploiting real macaque monkeys and forcing horses to work in direct sun, apparently in conditions so dire that one horse’s leg gave out on set”. A source close to the production, however, refuted the claims to the LA Times, stating that “there have not been any animal injuries or incidents” and that a certified representative from the American Humane Society was present during filming.

Perhaps, then, as these debates rage on, Hollywood could do with a reminder of the animal kingdom’s contributions to their work. There is, at least, the Palm Dog – established by film journalist Toby Rose in 2001, presented alongside the official jury awards at the Cannes Film Festival, and aiming to recognise the best in canine performances. The awards were inspired by Rose’s own Fox Terrier, Mutt, who was bought at a flea market in Champagne, has rubbed noses with the likes of Charlotte Rampling and Tilda Swinton, and even enjoyed a brief, on-camera career.

“People often ask how dog performances are judged and it is in the same way as for the Oscars or the Baftas,” Rose tells me. “The key is that indefinable but recognisable screen alchemy. When the performance stands out and seizes the audience – then you have your prize winner.” At last year’s event, Messi picked up the top prize for Anatomy of a Fall, joining previous recipients Mops, the timid but faithful pug of Kirsten Dunst’s Marie Antoinette in Sofia Coppola’s 2006 pop biography of the same name, and Brandy (portrayed by three dogs: Sayuri, Cerberus, and Siren), Brad Pitt’s valiant pit bull in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood.

Over in Los Angeles, a few critters have graced the Oscars stage through the years, but only ever as surprise guests. In 1998, Bart the Bear, star of Legends of the Fall and The Edge, helped Mike Myers present the Academy Award for Best Sound Effects Editing. Uggie the Parson Russell Terrier, who Rose believes was a “successor to Rin Tin Tin,” joined the rest of his cast on stage when The Artist won Best Picture in 2012.

And most recently, last year’s host, Jimmy Kimmel, attracted some minor controversy when he brought on stage a donkey he claimed was Jenny, the breakout star of The Banshees of Inisherin. The real Jenny, of course, was happily enjoying retirement back in County Carlow. Messi has already made a splash during this year’s Oscar season, having been photographed alongside the likes of Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling at the recent, snazzy pre-ceremony luncheon. If the Academy is really smart, they’ll let him present an award, too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks