‘It was painful to be a part of that process because she was so traumatised’: Ryan White on filming Pamela Anderson

The director tells Annabel Nugent why he believes his access-all-areas documentary based on the star’s own diaries has changed her future

When Ryan White first met Pamela Anderson, she wanted to know all about his mother. “We spent a good 30 minutes talking about my mom,” says the Emmy-nominated director. It was the first thing that surprised him about the Nineties bombshell, who was for a not-so-brief moment in time the most famous person on the planet. Literally. The second surprise was her sense of humour, which, he says, is dark and slapstick. “I really think Pamela has a whole second career in romantic comedies.”

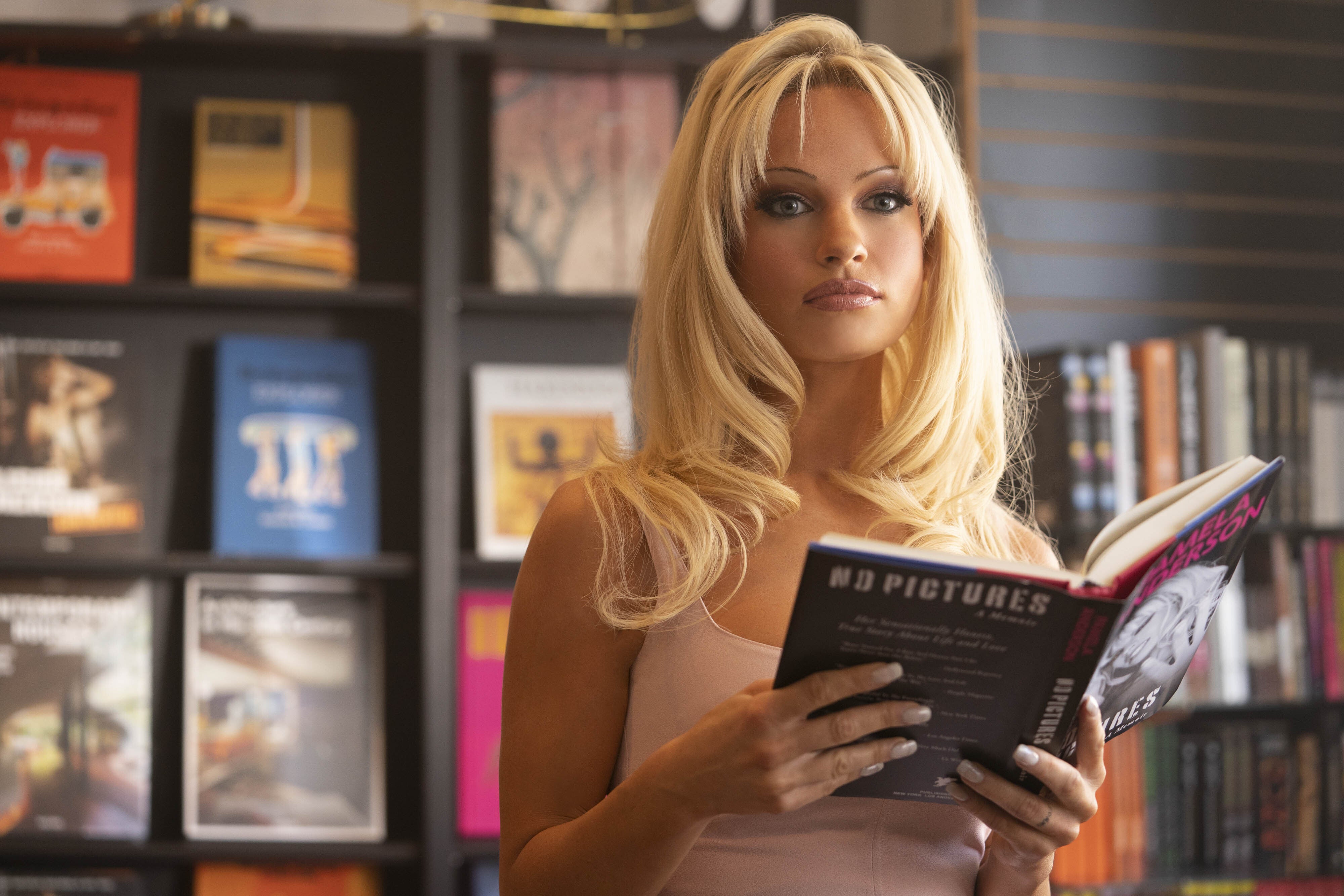

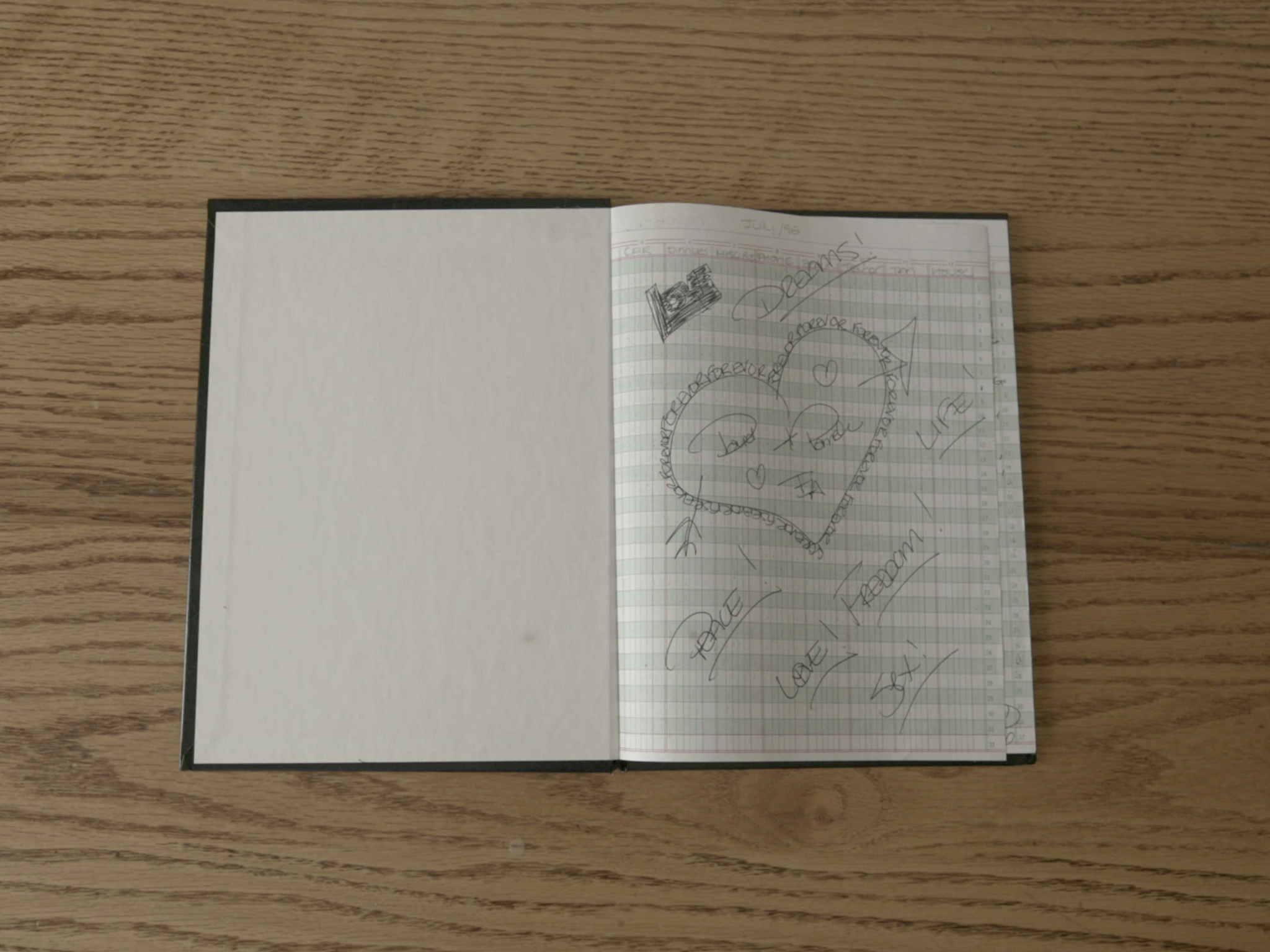

Her big heart and funny bone may not be what made Anderson world-famous, but they are what make the Netflix documentary Pamela, A Love Story so compelling. Made in collaboration with Anderson, White’s film unspools her life and career as we know it. On the surface, it is a two-hour tour through the big bullet points of both: Playboy, Baywatch, Tommy Lee, sex tape, that campaign against animal cruelty where she dons lingerie made from lettuce cups. But while the scenes are familiar, the perspective is new. For once, it’s hers. In fuzzy home videos, we see Anderson as a girl-next-door in Canada with a Botticellian beauty and toothy grin; in diary entries, we hear Anderson as a tender voice, searching and strong-willed. As it exists within those stacks of tapes and diaries, Anderson entrusted her life story to White. “We had so many diaries, we had to drive them back in a cargo van from Canada,” says White. “You can’t just send Pamela Anderson’s diaries with FedEx.”

Pamela arrives amid the slow-rolling wave of post-MeToo films that seek to rehabilitate female tabloid figures of the Nineties. In the past three years, there was Impeachment: American Crime Story on Monica Lewinsky, Framing Britney Spears on Britney Spears, Lorena on Lorena Bobbitt, whose name became a punchline after she cut off her abusive husband’s penis while he was sleeping. And albeit not a documentary, Blonde on Marilyn Monroe. Anderson is overdue a second look. Pamela finds her, at 55, living a quiet life at home on the Canadian island of Ladysmith, British Columbia, where she grew up. She is newly married to a local man, construction worker Dan Hayhurst, and spending time with her parents. She’s also writing poetry.

It would be warranted if Anderson wanted to release a documentary with the purpose of setting the record straight on her life (especially given the recent release of Hulu’s Pam & Tommy, which she has spoken out against – but more on that later). According to White, however, that was never the goal. In fact, there were no goals or agenda. She wasn’t after a redemption story. “There were no meetings about what she wanted to achieve with this documentary. None of that.” He pauses, adding with a laugh, “And typically you have a lot of that with celebrities because there’s a whole team of people around them who are part of every decision.” It’s why White steers clear of starry subjects. (His most famous subject before Anderson was tennis champion Serena Williams in the 2016 film Serena). “One of the huge draws about Pamela is that there is no one around her. She has no handler because, and she’ll admit this, throughout her career, she was told that she is unmanageable. She doesn’t like to be told what to do.”

You would not blame Anderson even a bit for hardening. Given everything – the childhood abuse, tabloid frenzy, domestic violence, stolen tape and the humiliation she suffered in court when she tried to sue over it – you might see a star whose edges have sharpened. Instead, Pamela depicts Anderson with the same quick smile and seemingly guileless candour of her youth. She has, against all odds, remained open. To White’s mind, perhaps to a fault. “It’s what makes Pamela beautiful but also why she’s been burned so many times,” he says. “I’m very protective of her now because I saw how she was with me.” Anderson handed over her diaries, her tapes, her unfiltered thoughts without a second thought. “I know that I can be trusted,” White tells me. “I know that I’m a trustworthy filmmaker and that I will deserve her trust at the end of this and still, I was like, ‘Oh my God, you are giving me your entire archive going back to when you were a teenage girl.’”

Anderson told White that nothing was off the table. Ask anything. “That’s not me being a dramatic filmmaker,” he laughs. “There was not one time where I asked Pamela something and she said she didn’t want to talk about it, or that she didn’t want that in this film. She doesn’t think that way.” White had complete editorial control – including final edit. “She didn’t even ask what was going to make it into the film.” Anderson did not even intend to watch the finished film. Similarly, she almost never looks at the photos from a photoshoot, White says. “Even her most famous shoots, she won’t look at the photos because to her, it’s all about being in that moment. The emotional connection with the person – and then whatever the product is later on, she doesn’t need to see.”

Later, White tells me that Anderson did end up watching the documentary but only because she found herself fielding questions in interviews about it. “I think she was starting to feel like, ‘Oh my God, I don’t even know how to answer because I don’t know what’s in the [documentary]’, because she played no role in the editorial process at all,” White says. “At all.” The only thing White needed sign-off on was the use of the home videos. “They’ve been burned by that archive [of tapes] before so I understand,” says White, seemingly in reference to the infamous stolen tape. Even then, it was her 26-year-old son Brandon – a co-producer – who gave approval; not Anderson. “There wasn’t one second I was told not to use.”

In its casualness, Pamela feels not unlike the many home videos that it features. The parts that aren’t made up of footage from her past – the VHS tapes, old Baywatch scenes, interviews with misogynistic, patronising talk show hosts – are stripped back and intimate. White didn’t use any lights in the filming and kept his crew to a minimum. Anderson did her own makeup. “Often it was just me with a camera and Pamela,” says White. “You see her shuffling down a hill in her little nightgown and slippers. She would just plop down on the couch and we would begin chatting.” What makes for a great film, however, can make for a “hellish” filming experience, laughs White. “She doesn’t want anything to feel contrived so if you’re shooting and you miss a line she’s not going to say it again.”

There is a conscious effort here to make Pamela as dissimilar in tone as possible to the splashy tabloid coverage that she has historically been filtered through. To some extent, though, it is impossible to excavate Anderson’s life of its headline-grabbing nature. So much of it was – and is – headline-grabbing. Even now, her recent claims that Tim Allen flashed her on the set of Home Improvement (something he denies) and that she walked in on Jack Nicholson in the throes of a threesome predictably made front page news. Her storied love life also provided much tabloid fodder – and if this was a different type of documentary, the men in her life might all feature as talking heads. “I think all of her husbands would be willing to speak. You could have [her former Baywatch co-star] David Hasselhoff, someone from Playboy, [her second husband] Kid Rock, Tim Allen…” says White. “But I didn’t want to make a Pamela Anderson biography. I wanted to be in her head, seeing through her eyes this weird fairy-tale type of journey. So sitting down with an ex-husband to look back at who she was wasn’t interesting to me.” Lee was the only one whom at one point White considered reaching out to. “I don’t know if he wouldn’t have participated, we never asked him. But it just wasn’t the type of film that we wanted to make.”

Much of Pamela focuses on her intense three-year marriage to rock star Tommy Lee, the drummer with heavy metal band Mötley Crüe, with whom she shares two children. Before White arrived, those videotapes sat unlabelled and unorganised in the attic of her grandma’s house. His team scoured pawn shops on the island until they found a TV old enough to play them. “We brought it into her beach house and spent two days popping in tapes totally unknowing of what was going to be on them,” recalls White. “Sometimes it was these magical moments between her and Tommy. And other times it was 15 hours of [her youngest son] Dylan playing with rattles on the floor, which is so boring as a filmmaker but she loved watching it.” A lot of Pamela hinges on those tapes, not only what is on them but how Anderson responds to what is on them. “I wanted to catch her face experiencing those memories. And I think in a lot of ways, the film is about memory. How do we romanticise the past and how do we move on from that?”

Early home videos show the couple infatuated and completely in love. They fawn over one another endlessly, but most surprising is how they goof around. They appear so happy that if what happened hadn’t been splashed on front pages across the world in 1998, you’d be surprised to learn that Lee was sentenced to six months in prison after he hit Anderson who had their six-week child in her arms at the time. Hours after he was charged with spousal and child abuse, she filed for divorce. Writing in her diary at the time, Anderson explains her decision to “my little Dilly”, her youngest son. “Mommy and Daddy will eventually be able to be friends one day, I hope,” writes Anderson, who chose to have an actor read the diary entries aloud rather than read them herself. “I want you to know that I would rather be alone than ever live with that abuse again. You will always be in a safe place.” The child abuse charges were later dropped. Lee served slightly less than four months of his sentence for the assault.

Other documentaries of its kind view their subjects solely through a filter of sympathy and passivity. What is most striking about Pamela is that Anderson is given agency, something which, in fact, she has always had. In the talk show interviews she gave over the years, Anderson would answer belittling questions from the hosts (always male) with a disarming frankness. When she found herself further ridiculed and objectified after hers and Lee’s sex tape was stolen, sold and leaked across the world, she weaponised the media’s misogyny and used it to shed light on her activism. As she puts it in her documentary, “They were already making fun of me. I may as well turn it into a good cause.”

She’s very willing to revisit trauma and pain and then relate it to the joyful moments, all in one answer

Anderson takes the good with the bad, a trait that manifests in the way she speaks. Her stories come looping, spiralling outwards further and further. “The synapses in her brain fire in very interesting ways,” says White. “She’s constantly pinballing all around her life. You ask her a question about Barb Wire [the 1996 blockbuster flop in which Anderson plays a bustier-clad bounty hunter] and she’ll start talking about a sexual trauma, Julian Assange, Vivienne Westwood. It’ll go back to Tommy Lee and to [her third husband, the professional poker player] Rick Salomon, then it’ll go to her sons. She’s very willing to revisit trauma and pain and then relate it to the joyful moments, all in one answer.”

Partway through filming the documentary, it was announced that Hulu was releasing Pam & Tommy, a dark comedy about the couple and their stolen tape. Lily James would play Anderson and Sebastian Stan was Tommy Lee; Seth Rogen would star as the man who stole the tape. “I think the series blindsided Pamela,” recalls White. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh s***.’ I didn’t know what Pamela was going to think about it. I didn’t know if she was involved in it.” She wasn’t. And neither was Lee. “I didn’t know what her thoughts were going to be because Pamela is very unpredictable. She doesn’t subscribe to any sort of ideology where you can predict which way she is going to go on any issue: politics, feminism, sexuality, anything.”

On Pam & Tommy, Anderson has made her feelings clear. She has previously denounced the series, revealing that she chose not to reply to James who wrote to her for approval. (In a recent interview, Anderson said she doesn’t “blame” the actor for taking the role.) There is a scene in Pamela during which Brandon calls to tell his mum that the series has begun airing on TV. Her unease is palpable. White recalls that his team knew the series had aired that night, but Anderson – whom he was with at the time – was evidently “clueless” about it. “She’s not very online. She’s very disconnected and I think people were deliberately keeping her disconnected during the week it was coming out so when Brandon calls and she’s starting to spin, that was all real. It was very painful to watch. It was painful to be a part of that process with her because she was so traumatised. She could barely talk about it.” It was the only thing that made Anderson clam up. “Whenever it came up, she wanted to get the f*** out of the room; she wanted to escape.”

For a series interested in consent, it is jarring that Hulu would go ahead without Anderson’s. Bearing witness to her pain in real-time “challenged” White as a filmmaker. “Every story is different and yes, I believe that storytellers need a right to tell documentaries about real people or celebrities or public figures but when you are telling a story about a living person’s sexual trauma – and you’re kind of making a comedy out of it – and you are focusing it a lot on the people who committed the crime against that woman…” he pauses. “I think you need that woman’s permission.” White knows that Pam & Tommy was, at least, largely sympathetic to Anderson. “I think it had to be,” he says. “That show would have been eviscerated if it hadn’t been. But the idea that she didn’t get a say in how that was told, the biggest trauma of her entire life was then played out in front of society all over again – I think that re-traumatised her in a way that has challenged me as a storyteller.” Now, White will never not think about those ethical issues in his work. “I’ve watched first-hand what it did to her.”

When they started filming, White envisaged a very different ending to the one that emerges. It was very Pamela, he jokes, that the story took a sudden turn. “We were expecting our narrative arc to be this beautiful story of Pamela Anderson returning to her island and finding love with a local to live out the rest of her life with – and we thought that was true,” says White. “But watching that footage stirred something up in Pamela that I believe changed the trajectory of what the rest of her life will be.”

Suddenly, White says, Anderson thought, “‘What the f*** am I doing? I’m only 53. I don’t need to die on this island. I’m rewatching the love of my life play out in front of my eyes. Why can’t I go back out into the world in search of love or have a second coming of my career?’” The third act of Pamela does not show Anderson putting herself out to pasture. In January last year, Anderson split from Hayhurst after 13 months of marriage. Months later, she would begin rehearsals for her exuberant Broadway debut as Roxie in Chicago. It is rare that anything, much less something as seemingly contrived as a celebrity documentary, will succeed in casting a new light on a subject that, as a result, will never again be seen the same but for many people, Pamela will do just that. At the very least, people will finally know that Anderson is very, very funny. The one thing she did ask White to consider when making Pamela: “Don’t let it be a complete sob story.”

‘Pamela, A Love Story’ is available to watch on Netflix now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks