The bait is over: Has the pandemic changed the Oscars forever?

As the nominations for this year’s Academy Awards show record-breaking diversity, it’s clear that change is afoot in the film industry. But it could be the sign of progress or just a pandemic-accelerated fluke, says Clarisse Loughrey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“The films nominated this year – the budget may be small, but in terms of storytelling, the scale is huge. They really are emotionally sweeping films,” says the producer Kathy Benz. In Minari and Nomadland, hope is cradled within the wide expanse of the American plains. In Judas and the Black Messiah, it lies in the hands of the people. And, in Benz’s film, Sound of Metal, a drummer with sudden hearing impairment rediscovers himself thanks to the love and support of the deaf community. In a year shaped by instability and uncertainty, Benz says that it’s been an opportunity for “reflection for all of us, industry and audience”. As a result, 2021’s Best Picture nominees capture the spirit of change.

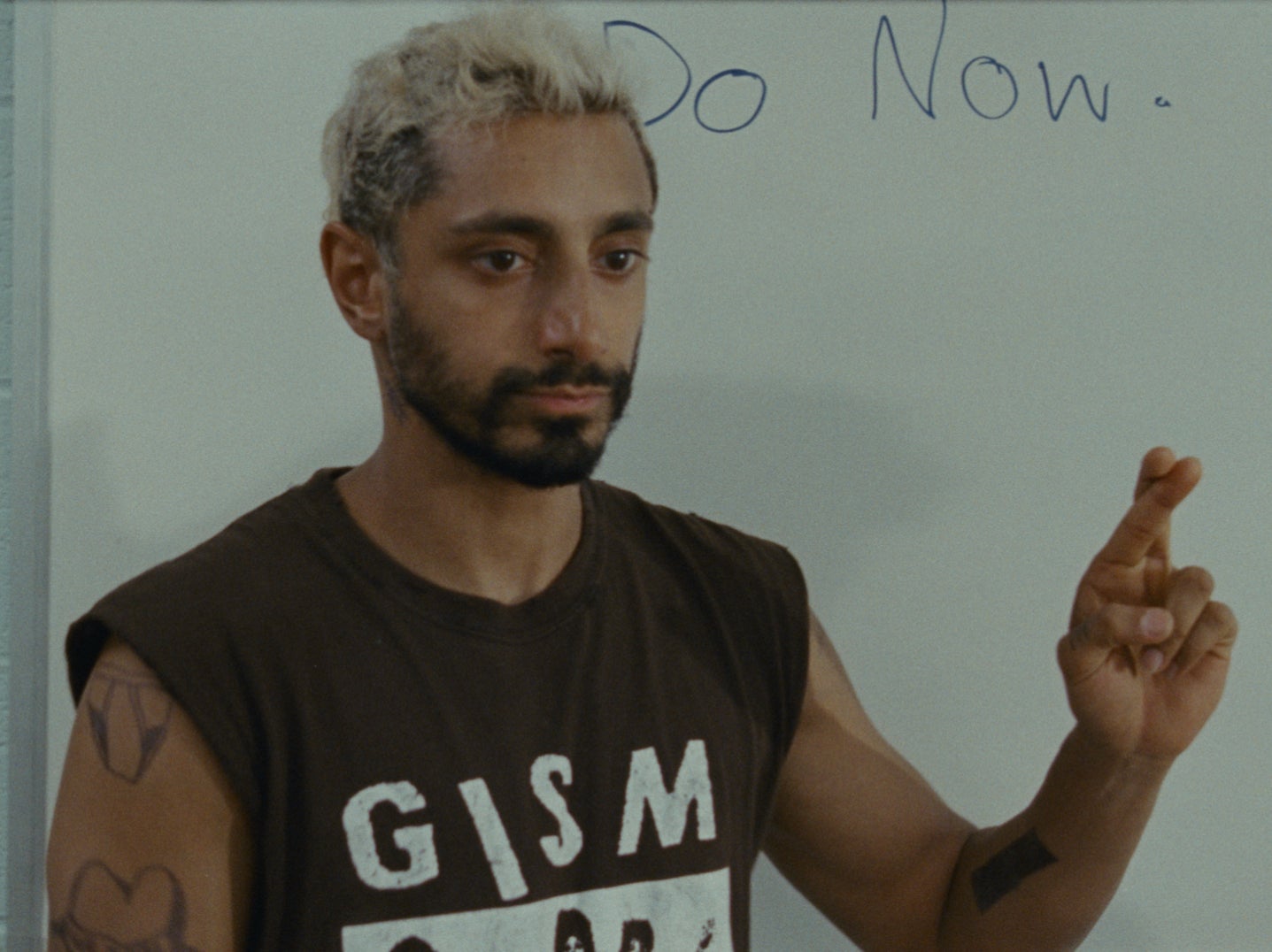

It’s an evolution that rejects, in part, the traditional idea of the “Oscar bait” – prestige projects with lavish sets and costumes, where A-list stars suffer beautifully or transform themselves beyond recognition. Instead, this year’s nominees are diverse, and in more ways than one: in onscreen representation, behind-the-scenes talent, and in ambition, theme and mood. The acting categories feature more nominees of colour than ever – Riz Ahmed is the first Muslim actor be nominated for Best Actor and Steven Yeun, the first Asian-American actor. Thanks to her role in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Viola Davis is now the most-nominated Black actress in Oscar history and the only one who’s been nominated twice for Best Actress. Chloé Zhao and Emerald Fennell became the sixth and seventh women ever to be nominated for Best Director – and it’s the first time the category has recognised two women at once. In total, a record-breaking 70 women received 76 nominations across the board.

But it’s impossible (and perhaps unwise) not to view these massive shifts within the context of a very strange, unstable time. The Academy Awards, originally scheduled for 28 February, were pushed back by almost two months due to the pandemic. The eligibility period was extended, while provisions were made so that releases could skip the required theatrical window – normally, a film must run for at least a week in both New York and Los Angeles to qualify. And so the question must be asked: is it naive or premature to celebrate the barriers broken by this year’s Oscars? Can we take this as a sign of greater progress, or was it a pandemic-driven one-off? In truth, there’s no clear answer. “You know the old, famous William Goldman quote about Hollywood, that nobody knows anything?” Benz says. “Well, the pandemic has given that phrase a whole new meaning. The industry is finding a new footing.”

Who knows how a low-budget film like Sound of Metal – whose director Darius Marder shunned A-listers for roles in order to stay faithful to the deaf community who inspired his story – would have fared in a pandemic-less year. In 2015, activist April Reign created #OscarsSoWhite to ensure the Academy took responsibility for its plague of all-white acting nominations – an issue which was replicated the very next year. The Academy, under the guidance of president Cheryl Boone Isaacs, has since expanded its membership in order to include a younger, more diverse set of 2,000 voters. And there have been tangible results: Moonlight’s win in 2017, and Parasite’s win last year, are both considered positive signs of progress. A decade ago, no one would have put much faith in a low-budget indie with an all-black cast or a darkly comic Korean thriller snagging the top prize.

But progress rarely travels in a straight line – when Green Book, with its reductive take on racism, won in 2019, it felt like the skeletal hand of the old, nearly all-white Academy had erupted from the soil to take one last swipe. “I still think it’s going to be a long fight,” says Benz.

There’s still much to do. Between 2015 and 2020, the actual percentage of female Academy members only increased from 25 to 33 per cent, while the percentage of members from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups grew from 10 to 19 per cent. Starting in 2024, any film qualifying for Best Picture will require proof of diversity in front of or behind the camera, within the film’s production and distribution, or in its career development opportunities. But the demands are so lenient that even a film written, directed, and starring cis, white, straight, able-bodied men could pass the bar if they cynically hired the right interns or publicity assistants.

For now, these rules seem more symbolic than anything. “I think that these new measures will be sort of a consciousness-raising exercise,” says Benz.

However, the absence of “a plethora of event films” this year has, Benz continues, left space so that “other voices can be heard”. A small batch of major studio projects were delayed until next year’s awards cycle, including Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story, Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, and Denis Villeneuve’s Dune. However, these were not, in themselves, obvious winners anyway. All three directors may command large budgets and the adoration of video essayists, but only one of Spielberg’s films has won Best Picture (Schindler’s List in 1994), while Anderson and Villeneuve are yet to win a single Oscar between them. It was never guaranteed that they’d land nominations.

What shouldn’t be underestimated is this year’s move to online campaigning. Previously, as a 2017New Yorker article estimated, studios were willing to spend up to $15m lobbying Oscar voters. There’d be screenings, Q&As, cocktails, luncheons, nominees flown all over the place, so that they could smile politely and shake an endless number of hands. All of that, of course, was put on pause this year – but studios were still able to splash out on extensive ad campaigns (which may have helped the cash-rich Netflix secure 35 nominations – close to the record set by United Artists in 1941). Screenings and Q&As relocated online, and voters have plenty of time to check out the competition. “For some films, it’s levelled the playing field,” says Benz. “Other elements have had more importance in terms of promotion – good critical reviews have been key this year, when in other years, you may have been able to gloss over that a bit with wonderful, shiny events.”

The fear at the core of all of this is that diversity will inevitably be treated as a temporary fad. When Halle Berry became the first woman of colour to win the Oscar for Best Actress in 2001, there was a sincere hope that the Academy had finally turned a corner. A woman of colour has not won since. While this year may feel like a new dawn for the ceremony, there’s a good chance that the second someone utters the words “Oscars Not So White”, the Academy will simply pat themselves on the back, declare racism solved, and fall back into the old habits and bigotries. Even if this year has been one of great change for the Academy, as Benz points out, it hasn’t quite extended beyond the top categories – to the effects, editing, and cinematography categories. “I think it’s going to take a more conscious effort on everyone’s part,” the producer says. “It’s going to take a lot more so that the industry doesn’t backslide and get lazy.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments