The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

One Life: The true story of Jewish heroism behind the Anthony Hopkins tearjerker

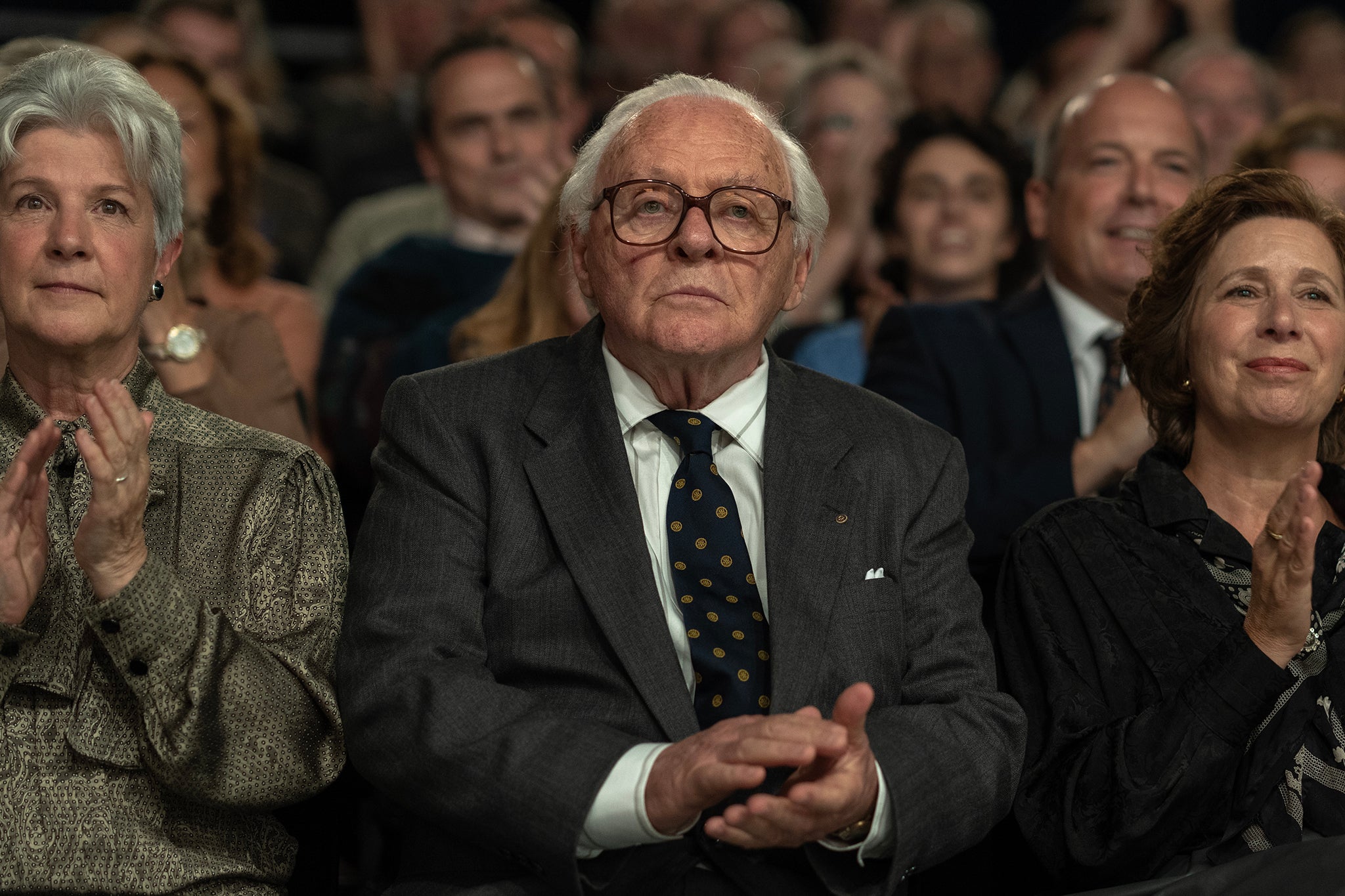

In his new film, Anthony Hopkins plays the real-life hero Sir Nicholas Winton, who was made famous in a landmark episode of Esther Rantzen’s BBC One show ‘That’s Life!’. Decades earlier, he facilitated the rescue of 669 Jewish children from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia. Adam White digs into his remarkable story

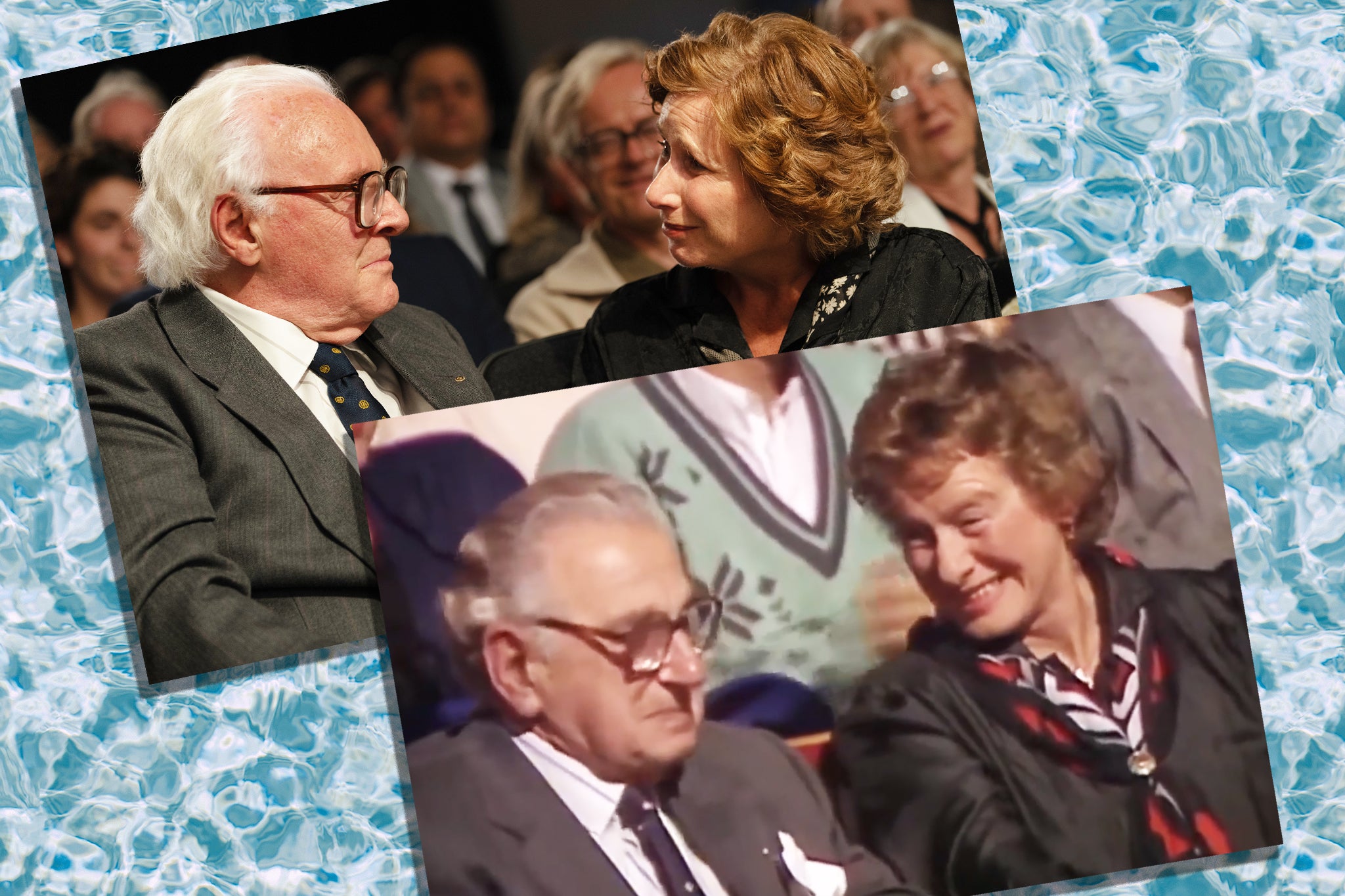

When he was invited to speak on a BBC consumer affairs show about his secret rescue of 669 mostly Jewish children from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, Sir Nicholas Winton was told he couldn’t sit alongside his wife. Instead, he would be sat between two strangers. But as the That’s Life! presenter Esther Rantzen informed viewers of her guest’s remarkable heroism, an explanation for the show’s seating arrangement came into view. The women on either side of Winton were two of the now grown-up children whose lives he’d selflessly extended just before the Second World War. As Winton fought back tears, more surprises were in store for him.

“Can I ask?” said Rantzen. “Is there anyone in our audience tonight who owes their life to Nicholas Winton? If so, can you stand up please?” What followed remains one of the most breathtaking moments of 20th-century television: the entire audience surrounding Winton were revealed to be children he had rescued, all of them now adults eager to thank the man who, until that very moment, had been the total stranger to whom they owed their lives.

This week, this landmark TV moment from 1988 – as well as Winton’s story – is recreated in a biopic titled One Life. Starring Anthony Hopkins and Johnny Flynn as the man in question at different stages of his life, the film also attempts to unravel why Winton did what he did, and why he kept his work a secret for 50 years.

Winton, who died in 2015 at the age of 106, didn’t want to be famous or even celebrated for his work. It’s partly why his story has always captured our imaginations – it’s impossible not to marvel over someone doing something so heroic for absolutely no glory or acclaim. Winton was determined to save lives out of a sense of moral duty, and spent his later years only wishing he could have done more. He remains a fascinating conundrum: a man made wealthy through the financial industry, but who was steadfastly socialist in his politics; firmly anti-establishment, yet heralded by that very establishment as “the British Schindler”.

Winton recruited a ragtag team of volunteers and began work out of his Hampstead home – sourcing permits from the German government to allow the transportation of child refugees overseas

The former stockbroker was just 29 when he witnessed the scourge of the Nazis firsthand. It was 1938, and Winton had travelled to Prague on holiday. Instead of skiing as he had intended, he visited a camp filled with hundreds of thousands of refugees, Nazis having already taken over the borders of Czechoslovakia. He was disturbed by the systems in place in the camp: the safety of adults took priority, the prevailing wisdom of the time being that they would be most at risk of harm by the Nazis. That, however, left children in the camp open to danger.

On returning to London, Winton recruited a ragtag team of volunteers and began work out of his Hampstead home – sourcing permits from the German government to allow the transportation of child refugees overseas, and fighting to allow said children into Britain. As much as we like to claim we welcomed the refugees of the Second World War with open arms, however, we did so reluctantly. Winton faced repeated stonewalling from authorities, and the cultural mood was not particularly charitable – as Esther Rantzen wrote in a recent comment piece for The Times about the new film, this was an era in which The Daily Mail ran a headline declaring “German Jews pouring into this country”.

The supply of visas from Britain was incredibly slow, while America refused to help entirely despite Winton writing letters to President Franklin D Roosevelt. “Governments could have helped,” Winton told The New York Times in 2001. “If America had said yes to me, we could have saved three times as many.” The situation in the UK was also complicated by the caveats placed on accepting refugees: each child had to be sponsored to the age of 18 by a British family to the sum of £50, an amount of money that few had at the time.

Between March and August of 1939, eight separate Kindertransport trains departed Czechoslovakia for London, carrying a total of 669 children. Winton met each train as they arrived, the children immediately being dispersed around the country to meet their adoptive families. Despite the lives he helped save, Winton was haunted by his inability to help more. A ninth train was intended to leave Czechoslovakia in early September 1939 but fell victim to the Nazis after they closed the border and invaded Poland – 250 children scheduled for the train would instead be marched into concentration camps, where they were killed.

After that, Winton retreated. “The day I stopped bringing the children, the war started, and during the war, I did something else,” he told The New York Times. “I didn’t know any of [the children]. It’s not that I didn’t want to talk about it, it’s just that there was no occasion to talk about it.”

Winton’s involvement in the mass rescue remained largely unknown over the subsequent decades. He would remain actively involved in anti-war operations, working for the International Refugee Organisation and then the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), both created in the aftermath of the Second World War to help rebuild Europe. He also created an organisation for the parents of disabled children, partly in tribute to his son, who was born with Down syndrome and died at the age of five from meningitis.

For the most part, records of Winton’s actions were confined to his extensive scrapbook from the time, which included the names and photographs of thousands of children – the majority he was unable to save, but many who survived because of his ingenuity. In 1988, Winton’s wife Grete passed the scrapbook to her friend Elizabeth Maxwell, a Holocaust researcher and the wife of the newspaper magnate Robert Maxwell. It was, undeniably, an incredible story, appearing soon in Maxwell’s Sunday People, and then on That’s Life!. Rantzen, who was friends with Elizabeth, was aware that Winton had wanted to reunite the children with the photos he had in his possession but had no idea how he’d go about it. She deployed the show’s team of researchers to find as many of the now-grown refugees as they could, before staging the surprise reunion for television. A less public reunion took place several months later, with Elizabeth Maxwell organising a private event for Winton and many of the Kindertransportees he rescued.

“I owe him my life and those of my children and grandchildren,” survivor Vera Gissing explained in that 1988 episode of That’s Life!. “I was lucky to get out when I did and having the chance to thank Nicky was the most precious moment in my life.”

In his later years, Winton was not only awarded a knighthood but also had statues built in his image and was given Czechoslovakia’s highest honour, the Order of the White Lion. But he never felt comfortable with the attention, often insisting that his allies who helped his operation on the streets of Prague were far more deserving of kudos. He also continued to raise awareness for genocides across the world, from Darfur to Rwanda.

When asked, during one of his final interviews in 2014, why he did what he did in the run-up to the Second World War, he answered: “Some people revel in taking risks, and some go through life taking no risks at all. I work on the motto that if something’s not impossible, there must be a way to do it.”

Speaking to The Guardian a year before his death, Winton argued for a new outlook on the world, sharing his vision for what humanity could achieve. “What is needed is something in which [people] can all believe irrespective of religion, which in most cases, dare I say it, is a facade,” he said. “We need something else, and that something is ethics. Goodness, kindness, love, honesty.”

‘One Life’ is in cinemas

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks