Noël Coward seems to belong to another, much more gilded era – so what is the secret of his staying power?

With new takes on Coward’s work coming to stage and screen, Geoffrey Macnab looks at the bon vivant’s enduring appeal and his overlooked contribution to British cinema

Thousands of people have talent. I might as well congratulate you for having eyes in your head. The one and only thing that counts is: do you have staying power.” Thus reads one of the many quotes attributed to Noël Coward (1899-1973).

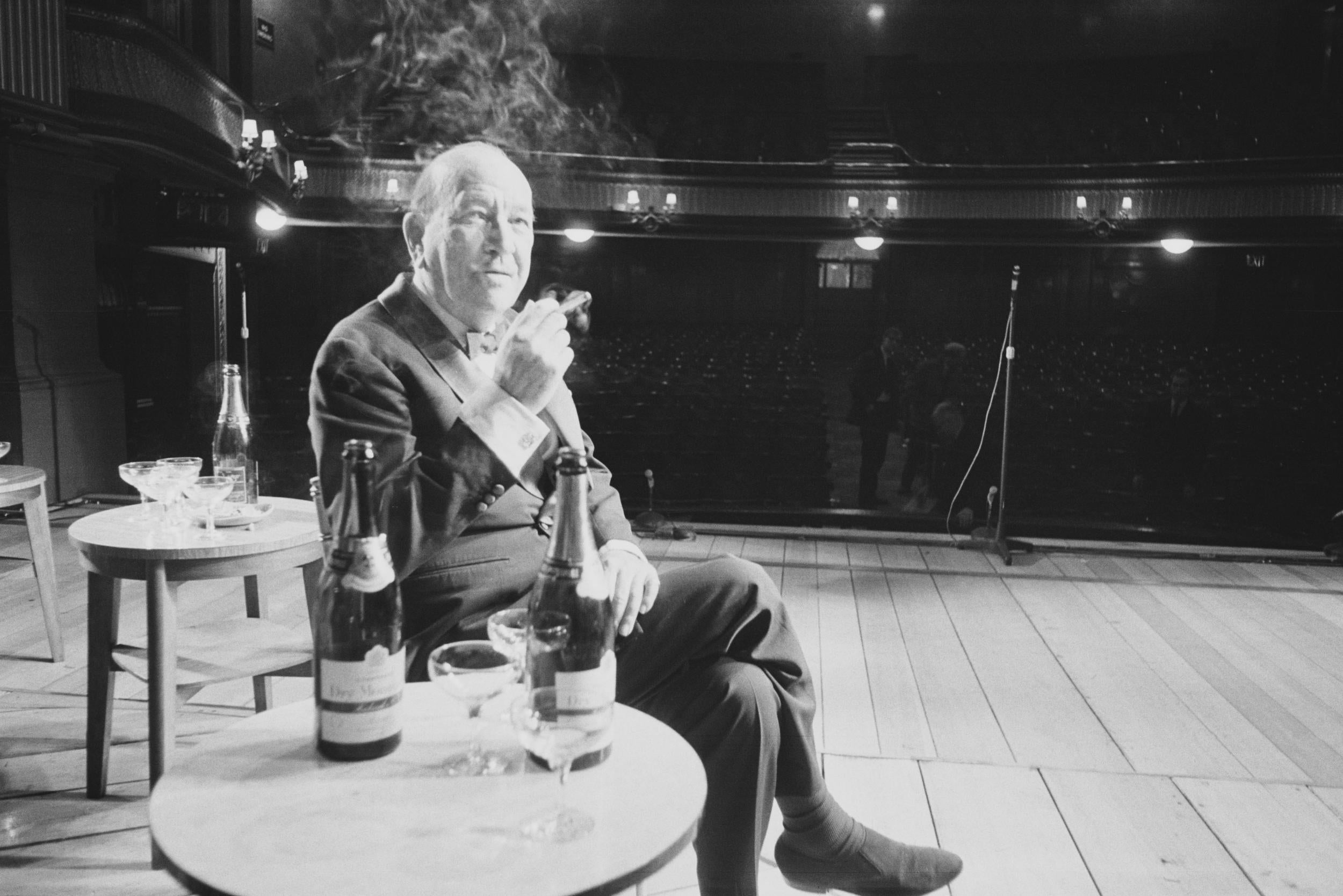

Coward’s own staying power is extraordinary. You’d have thought we have had enough of him by now. Think of the author, actor, singer, composer and general gadfly and the image that springs to mind is of a louche and camp figure in a silk dressing gown, smoking cigarettes through a holder, making frightfully witty remarks in an upper-class drawl, singing about mad dogs and Englishmen out in the midday sun and writing brittle, witty plays.

He seems to belong to another, much more gilded era. Nonetheless, Coward films and plays keep on coming. Movie distributors around the world have been fighting one another recently to snap up the rights to a new film version of his play, Blithe Spirit, directed by Edward Hall and starring Judi Dench as the eccentric mystic, Madame Arcati. The film (due to be released next year) also has American comic actress Leslie Mann as Elvira, the very svelte and glamorous ghost who comes back from the dead to haunt her writer husband (Dan Stevens) and to annoy his new wife (Isla Fisher).

Later this month, Matthew Warchus’s gender-swapping stage adaptation of Coward’s 1942 play Present Laughter at The Old Vic, starring Andrew Scott (of Sherlock and Fleabag fame) as the narcissistic actor Garry Essendine, is being beamed into cinemas across Britain. Warchus speaks of Coward as a playwright with sharp and contemporary insights about love, desire and the “trauma” of fame.

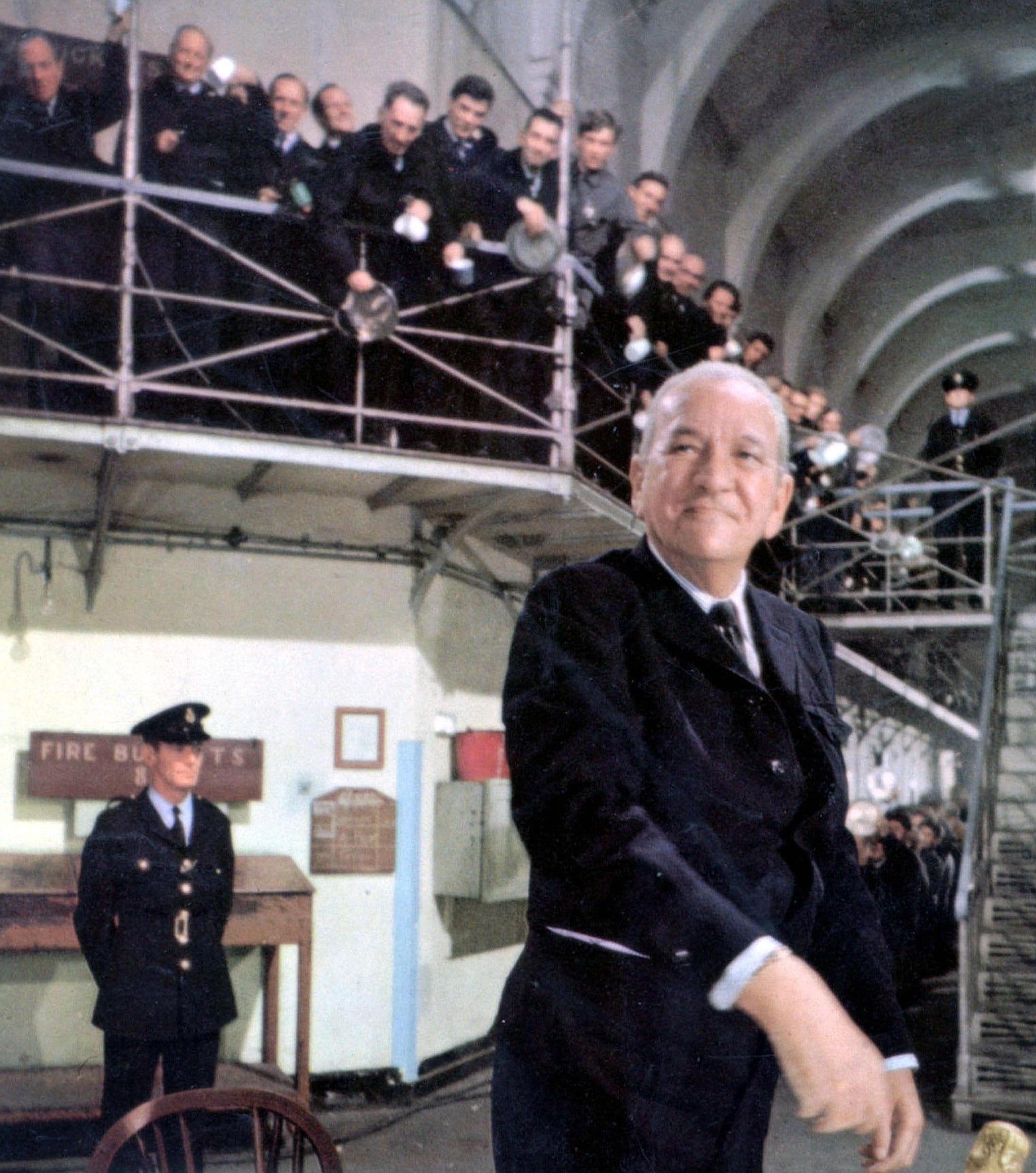

Coward’s contribution to British cinema is often overlooked. He is so familiar as composer, playwright and society figure that his involvement in some of the best films of the 1940s, in particular, is forgotten. If his cinema career is remembered at all, it is for his unlikely turn as the patriotic gangster boss Mr Bridger, holding court from the prison lavatory in The Italian Job (1969), the classic caper thriller released 50 years ago. The film, starring Michael Caine and made at the height of the Swinging Sixties, turned Coward into an unlikely symbol of cool Britannia. It was one of his more intriguing performances. He still rolls his Rs as if he is on stage but he also talks about “kicking the teeth in” of his robber crew if they don’t turn up with the loot. This was his final film role. As his biographer Philip Hoare note, it was made more than half a century after his screen debut in DW Griffith’s silent film Hearts of the World (1918). Like Ben Kingsley in Sexy Beast (2000), he was unlikely but inspired casting as the working class mobster.

Not that Coward had a high opinion of British cinema. “I had convinced myself, with easy sophistry, that it was a soul-destroying industry in which actors of mediocre talent were publicised and idolised beyond their deserts, and authors, talented or otherwise, were automatically massacred,” he later wrote. Coward railed against the inept way in which his own plays had been adapted for the screen, “rewritten by incompetent hacks, vulgarised by incompetent directors and reduced to common vacuity”, as he put it. That didn’t seem very generous given that some of Britain’s best filmmakers, among them Alfred Hitchcock with Easy Virtue in 1928, had tackled his work, and that Britain’s biggest star of the time, Ivor Novello, had starred as the troubled young drug addict in the film version of his play, The Vortex (1928).

The playwright was a natural-born show-off. That made him an easy target. His high-handed behaviour irritated the press that wasted no opportunity in trying to bring him down a peg or two. When he announced his plans to make In Which We Serve (1942), a wartime drama directly inspired by the naval career of Louis Mountbatten, the newspapers did their very best to sink the project before it could even be launched. He complained bitterly about the “sneering articles, contemptuous little innuendoes in the gossip columns, letters of protest written”.

What is most surprising about this and the other films with which Coward was associated in the 1940s was their modesty, their relative lack of snobbery and their celebration of self-effacing British decency. His 1942 film In Which We Serve which he co-directed with David Lean, was a propaganda picture, backed by the Ministry of Information, but it deals frankly with bereavement, wartime trauma, and cowardice. Its tone is never triumphalist. The Torrin, the ship under the command of Captain Kinross (Coward), sinks. Much of the story is told in flashback as the survivors cling to a life raft and think about the lives they’ve left behind at home.

Without Coward’s encouragement, Lean’s career might have turned out very differently. He hired Lean as his assistant. When Lean told him he wasn’t prepared to “do the work I’ll have to do without co-directing credit,” Coward agreed to give it to him.

As Lean’s biographer Kevin Brownlow points out, everyone had “heard of Noël” but few at the time knew Lean. Nonetheless, Coward worked alongside him and, at times, allowed the younger man to tell him what to do. “He accepted David’s direction and that acceptance added to David’s stature in the eyes of the crew,” Brownlow wrote of him.

Coward liked his creature comforts. Michael Caine remembered that he had “a free room for life” at the Savoy Hotel, offered to him because he had been playing cabaret there during the Second World War “and had sung on right through a night of terrible bombing and kept the hotel’s clients occupied and unafraid”. However, This Happy Breed (1944), his second wartime collaboration with Lean, was set a long way from the luxuries of London’s West End, in a suburban, lower-middle-class part of Clapham. Seen today, it seems like a forerunner of a TV soap opera. This domestic drama follows a family from the end of the First World War to the start of the Second World War. Coward’s portrayal of ordinary, salt of the earth Londoners may have been patronising and caricatured but this was still a moving and subtle affair, full of scenes in which Frank and Ethel Gibbons (Robert Newton and Celia Johnson) keep the upheavals of the outer world at bay by drinking cups of tea.

The playwright did not approve of Lean’s 1945 film adaptation of his play Blithe Spirit (“my dear, you’ve just f**ked up the best thing I ever wrote,” biographer Hoare quotes him as telling the director after the first screening). Nonetheless, Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945), adapted from Coward’s short play Still Life, was an instant masterpiece. A story about a middle-class, middle-aged woman (Celia Johnson) who almost has an affair with a doctor (Trevor Howard) she meets on a railway platform, had a huge emotional charge precisely because the two would-be lovers were so restrained. Only the swirling Rachmaninov music revealed quite how tempestuous their emotions really were and how much they struggled to curb their erotic attraction. The film ranked second in the BFI’s 1999 survey of the top 100 British films, behind only Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949). When academics and critics later pointed to its gay subtext, it only added to its richness. Brief Encounter was open to multiple different interpretations. It was Lean’s film but it wouldn’t have existed without Coward.

British cinema enjoyed one of its golden periods in the mid to late 1940s. Lean directed his celebrated Charles Dickens adaptations, Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948); Powell and Pressburger were in their pomp, making films like Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948); Ealing was turning out its classic comedies. One might have expected Coward to be at the centre of all this activity. Instead, he retreated. He simply didn’t seem to like the process of filmmaking, with all its repetitions, discomfort and longueurs. As a performer, he had immense charm when appearing live but, onscreen, he risked seeming very mannered. “I could never quite prevent a sinking of the heart every time I drove through the gates of Denham Studios – they recalled so many leaden and difficult days,” he later wrote. Being stuck in a tank, covered in oil and water and pretending to be a shipwrecked navy commander (his fate on In Which We Serve) was his idea of hell. Coward scripted The Astonished Heart (1950) and co-starred in it. He took occasional roles in other movies. However, his film career all but fizzled out.

Coward, though, had staying power. The TV and film adaptations of his work kept on coming. So did the one-liners about other people’s movies. (After he saw Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962), he famously joked that if Peter O’Toole had been any prettier, the director would have had to retitle it Florence of Arabia.) His direct contribution to cinema may have been slight – a dozen acting roles in 50 years along with four producing credits and a single directorial credit. Nonetheless, Brief Encounter and The Italian Job were enough on their own to carve him his own small but very distinct niche in British film history.

It’s hard to pinpoint just why Coward’s work still seems so relevant to modern audiences when he himself appears like a relic from a lost world. Perhaps the secret of his staying power is that he deals with such raw and primal emotions. Scrape away the gloss, snobbery and the self-consciously witty one-liners and you’ll find stories about love, loyalty and betrayal. In his films, he was also very acute in his observations of different strata of British society. He was also always alert to the absurdity in the behaviour of his characters, as well as to their quiet heroism.

The new film of ‘Blithe Spirit’ will be released next year; National Theatre Live’s ‘Present Laughter’ is in cinemas from 28 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks