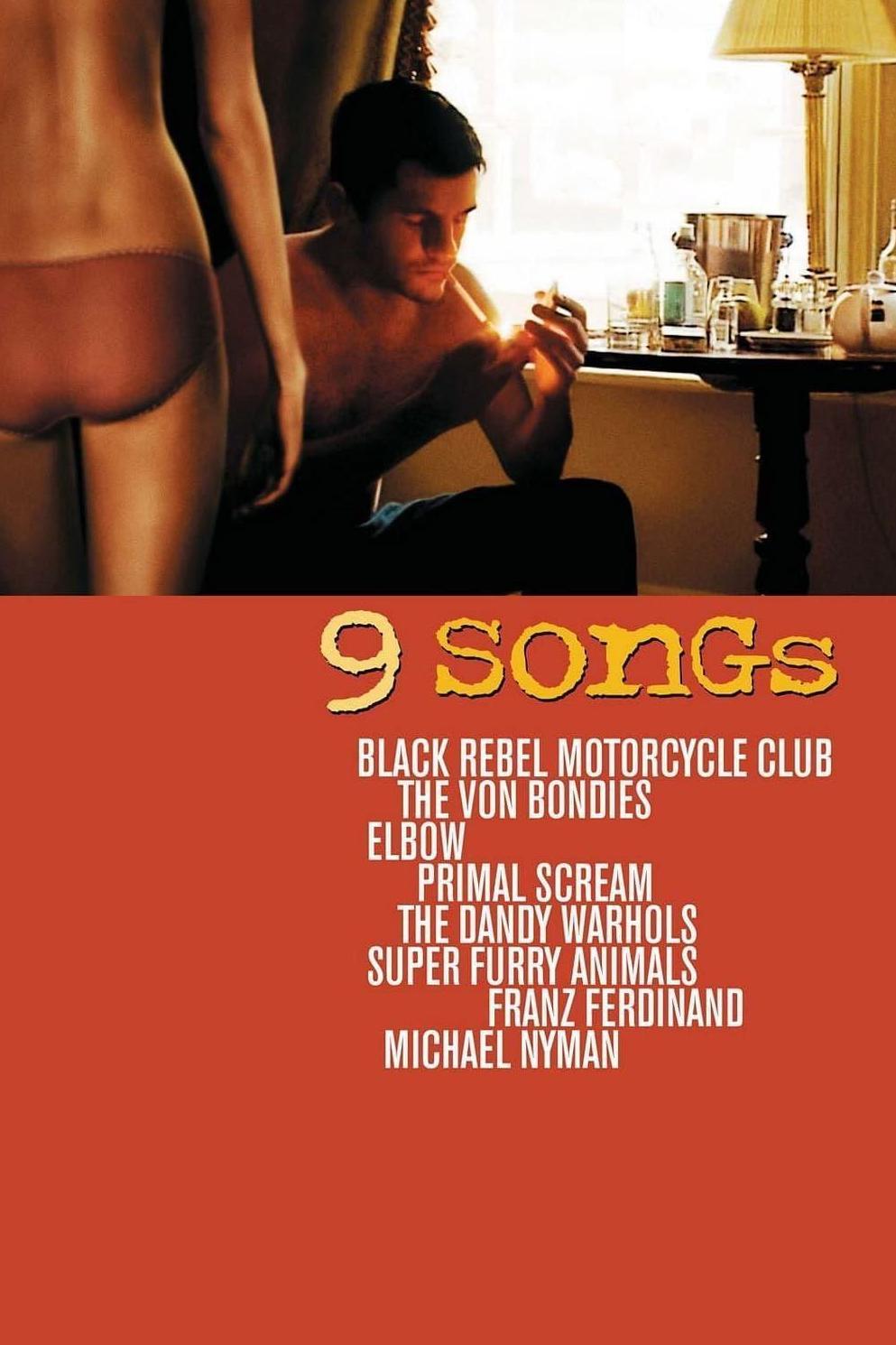

9 Songs: How the most explicit film of all time exposed our deep-seated fears of sex

As Michael Winterbottom’s ruthless satire ‘Greed’ hits cinemas, Adam White revisits the British auteur’s most provocative and scandalous experiment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If something sexy occurs in a movie and Ann Widdecombe isn’t there to complain about it, did it even happen? In 2004, Michael Winterbottom’s lo-fi erotic drama 9 Songs was blessed with the most sought-after note of controversy: an expression of pristine Widdecombe outrage. “It is not the BBFC’s role to allow pornography to enter the mainstream,” she blared at the time. “[Releasing the film] could be against the law!”

The source of the Tory MP-turned-Brexit Party MEP’s ire was the kind of movie that would barely cause a ripple in 2020, but only because something so low-budget and short in runtime (a giggle-inducing 69 minutes) would never get a significant cinema release today. Sixteen years ago, it received one, and a whirlwind of controversy alongside it.

9 Songs is an erotic drama-cum-concert movie, featuring graphic, unsimulated sex performed by two professional actors. Margo Stilley and former Coronation Street actor Kieran O’Brien are Lisa and Matt, and their year-long relationship is charted through sex and song – they meet at a gig, have sex, go to another gig, have sex, and so forth. Unlike Lars Von Trier’s Nymphomaniac (2013) or Gaspar Noe’s similarly explicit Love (2015), there are no body doubles, nor are there any camera tricks.

It’s the sort of experiment that could only have been made by Michael Winterbottom, one of the UK’s most singular filmmakers, and a director who has never stopped pushing the boundaries of acceptability in his work. His latest film, the capitalist satire Greed, has already caused a ruckus for its merciless depiction of a Philip Green-like fashion mogul. In recent years, he has sought dramatic inspiration from the murder of Meredith Kercher (in 2014’s The Face of an Angel), and released a film in which Jessica Alba is brutally beaten by her on-screen lover (2010’s The Killer Inside Me). To call him “daring” feels like an understatement.

9 Songs, however, remains his last truly culture-shaking picture – a film that riled the nation’s tabloids, caused at least one actor to be relentlessly hounded by reporters, and sparked discussions about how far cinema can (or should) go. It’s also far more interesting to think about than it is to watch, the furore surrounding it ultimate proof of how terrified and obsessed we are when it comes to sex. Considering who was responsible for the film, that may have been the point all along.

If 9 Songs has a modern legacy, it’s on Pornhub, where clips from the film remain incredibly popular among cinephiles of a different kind. Its presence on the DVD shelves of every charity shop in the country is also significant – pre-streaming, 9 Songs was one of, and perhaps the only, mainstream film with an 18 certificate to feature repeated scenes of unsimulated sex. That bands such as Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, Franz Ferdinand and Super Furry Animals were credited on the poster, in reference to the gig footage that breaks up all the fornication, also provided an air of non-mucky legitimacy. It could be bought in HMV and everything.

A factor, too, was how oppositional 9 Songs was to conventional pornography of the era. The sex in Winterbottom’s film is fascinatingly unvarnished, devoid of any artificial glamour or more cinematic flourishes. When Lisa masturbates Matt in the bathtub, every awkward squeak of flesh sliding against porcelain can be heard on the boom mic. Some sex scenes are so dark that it is difficult to discern what is happening and to whom. There are superficial elements to the film’s stars that place them firmly outside the average (O’Brien is well-endowed, Stilley has the height, face and bone structure of a fashion model – which she once was), but this is otherwise sex played as mundanely as possible, with even the film’s less conventional sex acts (voyeurism, S&M) still largely tame.

It could also hold the answer as to why 9 Songs created quite as big a stink as it did. The eye-popping shock of Winterbottom’s film hasn’t lessened since it was released – this is still a movie that features extreme close-ups of genitalia and oral sex, an on-screen ejaculation and a prolonged shot of penetration – but the sheer panic these scenes inspired in mid-Noughties tabloids has only become more embarrassing over time.

Endlessly referred in headline shorthand as a “sex film”, 9 Songs ignited immediate controversy when it was screened in front of a specially selected preview audience at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival. Reporters couldn’t believe that O’Brien and Stilley had, by all accounts, met, had sex on camera and then gone their separate ways – let alone that a director of such note (Winterbottom having recently released the acclaimed 2002 music biopic 24 Hour Party People) could make something so “pornographic”.

Mystery surrounding Stilley, the less experienced of the film’s two stars, only deepened once it was claimed that she refused to publicise the film at Cannes – not out of shame or any kind of trauma, but because she wanted “Lisa” to stand on her own two feet as a separate entity from herself. She would later relent, joining O’Brien and Winterbottom on the publicity circuit – but not before tabloids had dug into Stilley’s personal life, sent reporters to her mother’s North Carolina home and stalked her younger brothers on their way to school.

“People were really angry with me,” Stilley told The Daily Telegraph in 2008. “When I did press conferences people would shout abuse at me ... I got told I was a whore and a slut and how could I do it. And what kind of role model did I think I was giving young women?”

O’Brien, who spoke in interviews with a nonchalant defiance about his participation in the film, experienced a far easier ride – much like Vincent Gallo and Mark Rylance before him, both of whom participated in unsimulated sex acts with female actors on-screen (in 2003’s The Brown Bunny and 2001’s Intimacy respectively), but received none of the vitriol levelled at Chloe Sevigny and Kerry Fox, the women they were respectively filmed with.

“I wanted to make a film about something I really believe in, which is to show sex in a very positive light,” Stilley told The Guardian. “What I find in films I see is that sex is always a turning point in action, someone’s cheating on someone, or someone dies. It’s always the kids having sex in horror films that die. And I didn’t like that.”

In his own interviews, Winterbottom said that he was inspired to make the film partly because of our warped relationship with sex on screen. “You can show people eating and doing normal things, but you can’t show two people making love, the most natural of all things,” he told The New York Times. “That’s insane.” He therefore pitched the film to his stars as a story of “a love affair from the point of view of making love”.

Whether it was pornography and not a legitimate piece of art became the main conversation once 9 Songs was submitted to the British Board of Film Classification. Once it was allowed to be released uncut, and with an 18 certificate, the movie was dubbed “the most sexually explicit mainstream film ever made”. The campaign group MediaWatch, founded by the infamous “family values” crusader Mary Whitehouse, accused the BBFC of “normalising hardcore pornography” by allowing the film to screen in high-street cinemas.

Undeterred, Winterbottom insisted that he wanted 9 Songs to be publicly screened. “I want it to be shown in cinemas and not be ghettoised in sex shops,” he told The Guardian. “It’s not a pornographic film at all … We wanted to try and deal with a part of the relationship which most films just avoid completely.”

Watched today, 9 Songs works better as a statement on sex in cinema than it does as anything else. It’s often cringe-inducingly po-faced, from the narration that compares the icy landscapes of Antarctica to a fledgling relationship, to Matt mournfully realising his fling with Lisa is over when he spies her going to town on herself with a vibrator.

However, the film does still have radical power. 9 Songs is transgressive in the silliest sense, in that ordinary sexual activity still remains striking when depicted without any modesty whatsoever.

While O’Brien has since managed to land roles in Mike Leigh’s Peterloo and the hit HBO miniseries Chernobyl, Stilley hasn’t been able to emerge from under 9 Songs’ shadow. That she hasn’t, though, is also a statement on how impactful she was here. She, O’Brien and Winterbottom weren’t just part of something that pushed boundaries for a hot second, but for more than a decade after the fact. They should be proud as much as we should collectively be embarrassed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments