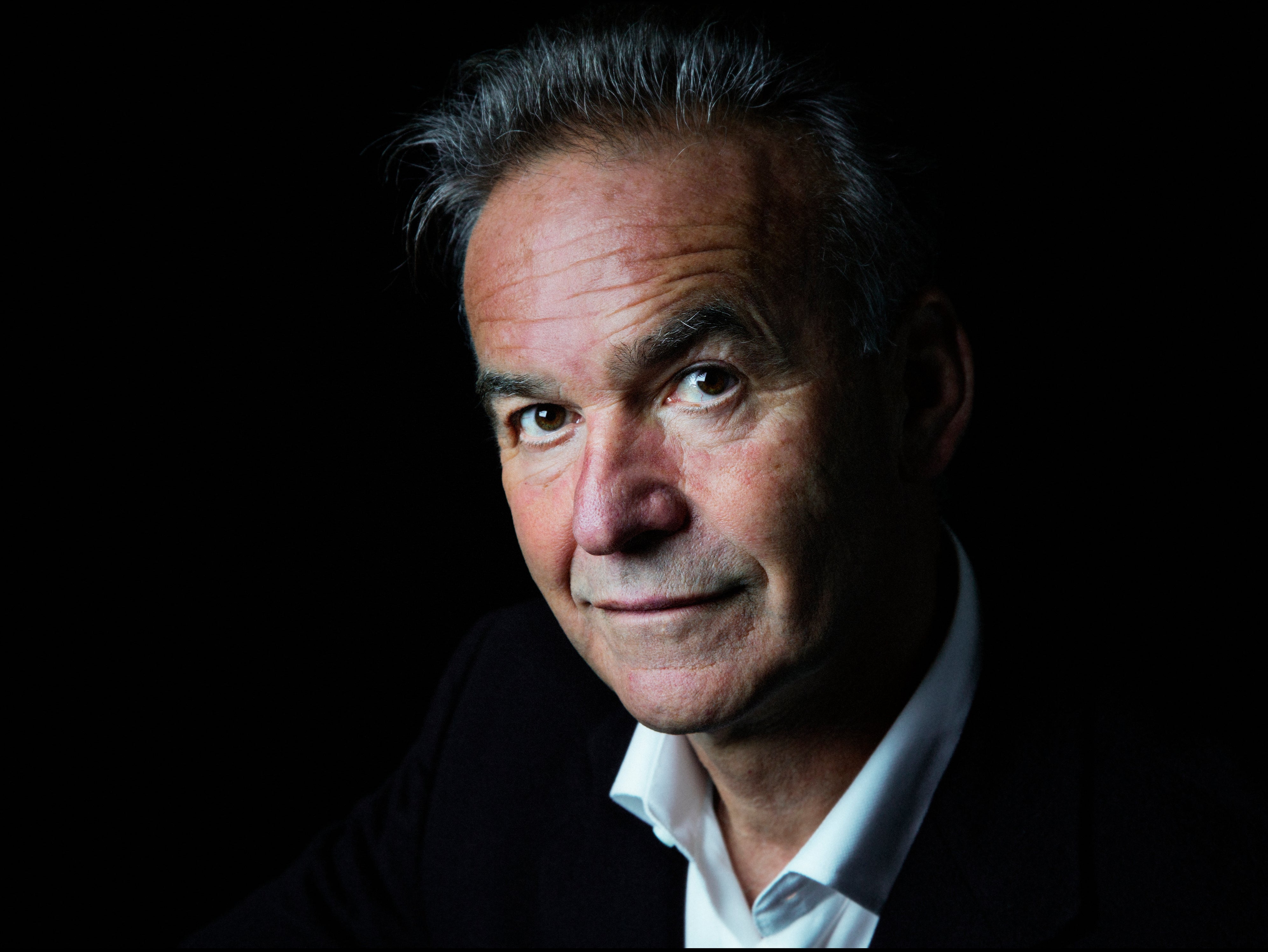

Nick Broomfield: ‘I was beyond terrified when I confronted Courtney Love on stage. I was in a state of numbness’

The gonzo filmmaker has made a career out of turning setbacks into strengths. He talks to Ellie Harrison about his confrontational style and how he changed tack for his most intimate film to date

Nick Broomfield thrives on conflict. The prolific documentary filmmaker has been sent death threats by arms dealers, had a cameraman refuse to ever work with him again, and had one of his films banned by the government for its portrayal of the British police. All of this only encourages him. “I function very well in chaos,” he says, grinning.

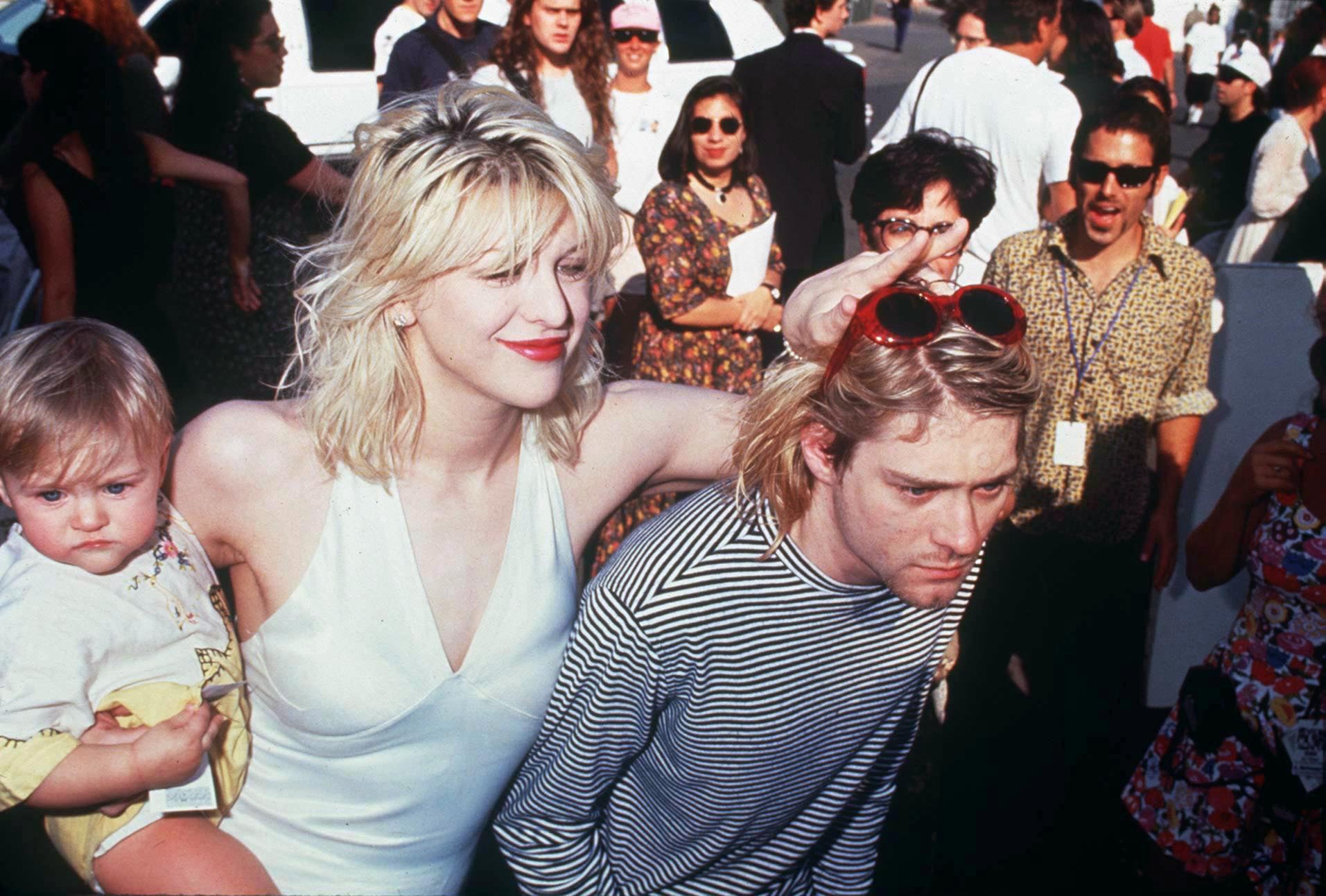

Across his 50-year career, Broomfield has earned a reputation for portraying his subjects with both tenderness and unflinching honesty. In his 2002 film Biggie & Tupac, he’s eating homemade beef soup with Biggie’s mother one minute, fielding abusive phone calls from Death Row Records the next. His 1994 Thatcher film sees him crash the politician’s perm appointment in a bid to get an interview. In 1998’s Kurt & Courtney, he meets Cobain’s old housemate, who explains that the Nirvana star wore so many layers because he was embarrassed by his slender physique. He became “oddly close” with serial killer Aileen Wuornos after making films about her in 1992 and 2003. Broomfield’s latest film, My Father and Me, which reflects on his complicated relationship with his father, is his most intimate to date – but it’s as unvarnished as the rest.

Broomfield has previously described the filmmaking process as “torturous”. It’s easy to see why. He consistently goes where he’s not welcome and is often filmed being kicked out of places, protesting, “I was just asking a little question!” While traditional documentaries leave out the antics that go on behind the scenes, Broomfield keeps it all in: the failure to get interviews, the abuse he receives from contributors, attempts at censorship, even his own fumbling for words. His self-reflective style paved the way for Louis Theroux, who in 2017 said Broomfield “represents a gold standard for the kind of documentary-making I aspire to do”.

Perhaps the most daring of Broomfield’s stunts appears in the 1998 documentary Kurt & Courtney. The film was intended to be a study of the Nirvana star Kurt Cobain, his death aged 27 and his romance with Hole’s Courtney Love. But after Love launched a full-scale attack on the documentary – banning Broomfield from using Cobain’s music and pressuring MTV into withdrawing funding midway through filming – it became an exposé of Love’s seemingly controlling nature. In the film, Broomfield gets up on stage, uninvited, at the ACLU awards dinner and calls out special guest Love for manipulating and threatening journalists. “I don’t want to be a party pooper,” he declares to the audience, “but in the interest of free speech I wanted to ask a few questions...” Within seconds, he is heckled by the awards president and escorted off stage.

Broomfield, 73 and speaking over Zoom from the mountain town of Ojai in California, chuckles at the memory. “I got an out of body feeling from that,” he says, in his signature languorous drawl, smoothing down every letter “T” into a letter “D”. “I’d been on the shoot for 14 weeks – our budget was for about five. Our crew was completely not paid. I did it completely out of desperation to try to get an ending. I remember when I was up there saying the words, I was looking at my hands and thinking, ‘My God, those are my hands.’ I was just so detached from my body. I was beyond terrified. I was in a state of numbness.”

The footage of this moment was taken by a random guest, because Broomfield’s cameraman had a panic attack and left. “The guy would never work with me again,” he says. “He was so traumatised by what happened.”

The film does not look favourably on the grunge star, but Broomfield’s interview with her father, who goes on a bizarre rant about his “great war” with his daughter, goes some way to explaining Love’s behaviour. In recent years, a number of films have reassessed how female musicians were treated by a misogynistic society. Is there anything Broomfield would do differently if he were to make Kurt & Courtney again? He pauses for a long time. “My films are very much reflective of my experience of making them,” he says eventually. “They are almost like a diary. I never set out to make a specific point. The points have always evolved as I’ve become convinced of something along the way.”

He had far more sympathy for another of his subjects. Aileen Wuornos was convicted of murdering seven men between 1989 and 1990 and sentenced to death. Broomfield made two films about her, one in 1992 called The Selling of a Serial Killer, and another in 2003, Life and Death of a Serial Killer. For the latter, she invited him to interview her the day before her execution. “We became oddly close,” he says. “Her end was so tragic."

In spite of three state psychiatrists assessing Wuornos before her death and finding her sane, Broomfield says she was “clearly of unsound mind”. “She thought her mind was being controlled by some kind of communication device within the prison,” he says. “She was just totally paranoid and hearing voices and was scheduled for execution. It seemed to me, on that level alone, completely inhumane.”

On the eve of Wuornos’s execution, Broomfield asks her if she’s going to be OK. She says that she will, that death is going to be “like Star Trek beaming me up into a space vehicle”. It is desperately sad to watch.

Wuornos suffered abuse throughout her life. She was raped by her grandfather and her brother as a child. “She had been living like a feral animal,” says Broomfield. “Not going to school from the age of 12 or 13. The social services, what there are in America, had never tried to find her or do anything. Then she’d ended up on the road… She was this poor creature who had been so abused and traumatised. I just really felt for her. Sometimes you’re very moved by somebody or something, very unexpectedly. It was very difficult for me to talk about it for quite a long time. I’d get very upset.”

Broomfield believes the system failed Wuornos. And it frustrates him that his documentaries have not led to meaningful reform in the institutions he calls out. “You go into it thinking there will be repercussions,” he says. “And there just aren’t.” He points to his 1976 film Juvenile Liaisons, about the police’s heavy-handed treatment of children, which was banned by the serving Labour government. “There was a parliamentary enquiry but no repercussions in terms of the police force,” he says. “The poor policemen and women who had the ill fortune of being in the film, who were regarded as the best in the force, were put on leave and suspended and it finished off their careers because they were scapegoated. There was no real introduction of proper training for police who were dealing with traumatised kids on a psychological level. None of the positive things that should have come out of it were enforced. The institutions carry on in exactly the same way. That’s what institutions do. None of it really has very much effect.”

It is perhaps this lack of faith in systemic change that explains Broomfield’s reluctance to tackle the subject of Harvey Weinstein – something he considered 15 years ago, well before the allegations against him were made public.

“A friend of mine worked for Harvey for two or three years as his right-hand person,” says Broomfield. “I remember his awful stories and vaguely thinking maybe one should do something on that. There were obviously other people who could talk. Rumours everywhere. My friend was the one not only making the women feel better but also all the guys he crushed, whose films were decimated, who were a shadow of their former selves. He was trying to put them back together again and control the damage. He was a mess from it, too.”

This friend, says Broomfield, would come and stay with him down in Sussex and “recover”. “It was certainly out there for a long time before s*** really hit the fan,” he says.

Why did he decide not to make the film? “It was all so unremittingly ugly. It was just so dark and grim.” This doesn’t seem to have put him off before. “I didn’t know what would come out of it that would become particularly positive,” he says. “I mean, a whole movement came out of it, but I didn’t see that at the time. You just heard these awful stories about him and the other people who were enabling him.” Broomfield’s friend, meanwhile, quit his job and “received a lot of therapy, years later”.

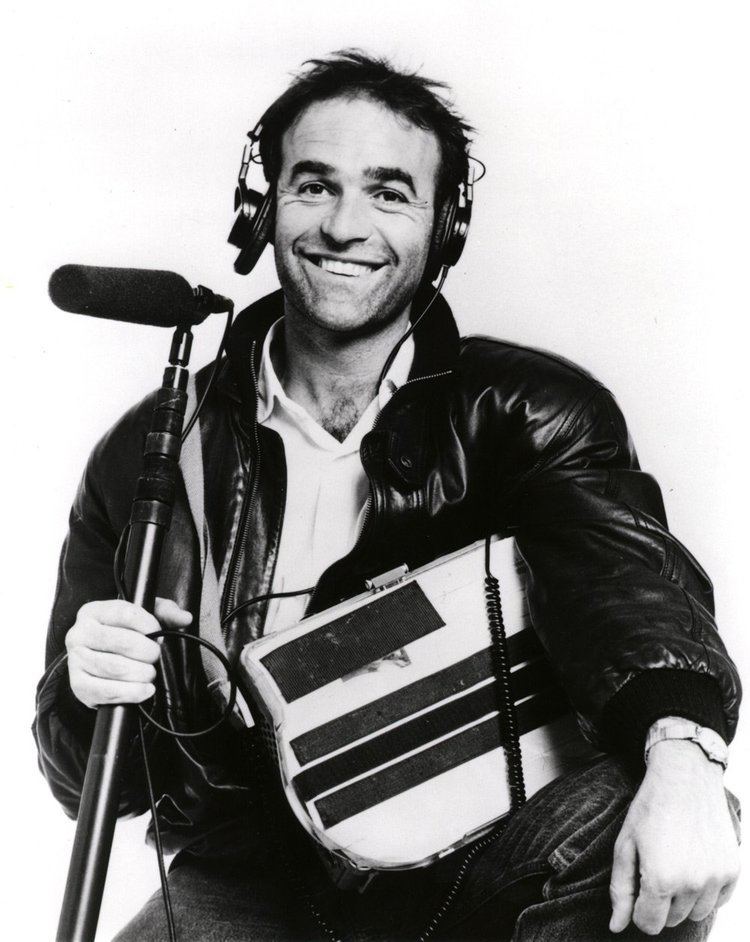

The director’s latest film, My Father and Me, is a much less confrontational project. But Broomfield doesn’t shy away from his and Maurice’s differences. “As a young kid I worshipped Maurice, I loved his smell, his laugh, everything about him,” he says in the voiceover. “As a teenager, I became more rebellious and questioning.” The pair were the best of friends by the time Maurice died, aged 94, but their relationship wasn’t always easy. In the film, Broomfield ex-wife, the cinematographer Joan Churchill, points out that Maurice never said he was proud of his son. “If you could only turn the camera on Nick Broomfield at this moment,” she says, “you would see that he’s actually crying.”

Broomfield was born in 1948 to an eccentric family. His father was a factory worker turned photographer from Derbyshire, his mother Sonja a Jewish refugee from Slovakia, his uncle a David Attenborough collaborator with a pet honey bear he walked around Hampstead Heath.

“I’d always been very frightened about making something so intimate about my family,” Broomfield says. Even talking about it now is clearly uncomfortable; he sighs deeply and leaves sentences unfinished. “In doing it, I disappeared into this tunnel of memory and thought and emotion. I got more and more sucked into it. Family memories are very intense, aren’t they?”

Maurice was known for his vivid, cinematic images of industrial post-Second World War England. He had a gentleness and a determination to see the beauty in things that made Broomfield want to rebel against that creative style. “It made me more defiant,” he says. “I found his not wanting to confront things frustrating, and sometimes I felt it wasn’t a strength. Because problems don’t go away. Some things you have to deal with, as painful as they are. One of the things that was really terrible was when he was clearly dying he wouldn’t recognise that fact. My son Barney wanted to say a last goodbye, but he couldn’t.”

Maurice never acknowledged that Sonja, Broomfield’s mother, was dying either. “He couldn’t be with her when she actually died,” says Broomfield. “He inhabited this quite romantic world that he didn’t want to come out of. Our differences obviously translated into our work quite profoundly.”

The only other film in which Broomfield includes his personal life is Marianne & Leonard. It’s the story of the relationship between Leonard Cohen and his Norwegian muse, Marianne Ihlen, with whom Broomfield also had his own brief affair. He says making the documentary was “kind of wonderful”. It is not the most flattering portrait of Cohen. One critic wrote of the film, “Marianne gets lumbered with the thankless job of being a ‘muse’ – effectively serving up sandwiches and sex to Leonard Cohen while he chomps on fistfuls of drugs and writes an unreadable novel.”

What did Broomfield think of Cohen? Did he like him? “I never knew Leonard terribly well,” he says. “I met him after [I was with Marianne] completely independently in Los Angeles. We were both dating actresses” – my detective work tells me Broomfield was going out with English actor Amanda Donohue and Cohen was with Risky Business star Rebecca De Mornay– “and we’d be the extra partner, you know, the wallflower, at all these Emmy events and stuff. We would have long conversations. I have an enormous admiration for Leonard. He had this incredible charisma that profoundly affected people. He was obviously a magnet for women. He was also full of mischief and was remarkably honest about himself and his shortcomings. I don’t think he pretended to be anything other than what he was.”

As for what comes next, he says his forthcoming projects could be a “smorgasbord of different things”. He has just finished one film about the Nineties music label Death Row Records. “It was the complete opposite to Marianne & Leonard and My Father and Me,” he says. “This one was much more confrontational again. It was much more of a slog getting through it. I missed the intimacy of the other ones.”

He smiles at how apprehensive he had been about making the family film. “Intimacy is intimidating,” he says, “but it’s also such an experience.”

My Father and Me airs at 9.45pm on BBC Two on 20 March and will stream on BBC iPlayer

The V&A Museum will celebrate the work of Maurice Broomfield in a display of his photographs and the publication of a book, Maurice Broomfield: Industrial Sublime, later this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks