We sat down for dinner cooked by one of Chef's Table Season 3's chefs

The series has become a hit for its in-depth interviews with world class chefs. Kaleem Aftab meets two of the culinary masters featured in the latest season

The popular Netflix series Chef’s Table added a new ingredient to the cooking show formula when it launched in 2015: each episode profiling a different world-renowned chef. Netflix launched the third season by screening two episodes at the Culinary Cinema section of the Berlin International Film Festival, one about Berlin-based Michelin-starred chef Tim Raue and the other featuring Zen Buddhist monk, Jeong Kwan, who has become a sensation of the cooking world despite not owning any restaurants.

The episodes could not have been any more different. Raue comes across as a man driven by his own ego. He describes how he grew up as part of a gang in the Kreuzberg district of Berlin, before discovering cooking. But his passion seemed to be to get to the top of the rigid chef chain as fast as possible. Once he became a head chef, Michelin stars were, of course, his next goal.

In the kitchen of his own restaurant, Restaurant Tim Raue, he is the gaslight. Nothing gets done without his approval. He’s the strong authoritarian figure.

It’s like a cleansing of the palate when the episode featuring Kwan airs straight after. After the bustle of the Raue kitchen, we enter the serene environs of a temple in Baekyangsa, around 150 miles south of Seoul, South Korea.

Kwan’s cooking became the talk of the restaurant world after she was invited to cook at New York’s Le Bernardin by the French three-Michelin-starred chef Eric Ripert, a Buddhist who visited Kwan’s temple as Korea’s reputation as a hotspot for cooking began to grow. Ripert ate lunch, and was so blown away he couldn’t wait to tell his friends about his discovery.

One of the guests at Kwan’s Le Bernardin meal was New York Times food critic Jeff Gordinier, who was so amazed at the cuisine on offer he called her “The Philosopher Chef”. He’s featured in the episode Kwan talks about religion, sharing and food made to calm the soul.

Someone on the organising committee clearly seemed to have a sense of humour when they decided to pair these two episodes together. These are chefs who seem to have nothing in common. It actually seems a shame that the post-screening dinner is going to be cooked by Raue, when it’s Kwan who has entered our hearts, soul and stomachs.

The venue for the dinner is a beautiful red marquee tent that looks like it’s been designed for the Chinese State Circus. It has a magical quality to it. It’s a venue designed for showmen.

On stage the German and Korean chefs are introduced, as are the series creator of Chef’s Table, David Gelb, and Abigail Fuller who directed the episode featuring Raue. Fuller stands at the far stage from Raue, and it’s no surprise when it’s revealed that they butted heads on set. Raue didn’t like anyone else giving orders to him in the kitchen.

Raue is wearing his restaurant’s blue uniform rounded off by gregarious red trainers. Next to him Kwan looks like she is preparing for Bunraku. She’s wearing a grey seungbok, the clothing traditionally worn by Korean monks.

Yet Raue soon starts winning me over. First up, he has called his menu Yin and Yang and is so aware of the treatment he’s been given on Chef’s Table that instead of steam pouring out of his nostrils, he runs with the gag, announcing, “I’m not such a bad guy. I’m really nice. So in honour of our Korean guest I have cooked a dish in her honour and style.”

That’s not an easy task. Temple chefs cook food that they have grown themselves and nurtured in their gardens. There is no dairy or meat. It’s vegan cuisine. But then comes the kicker, Kwan also doesn’t use onions, chives, shallots, leeks or scallion to cook either. Monks need to eat food that makes them feel calm and serene, and these pungent spices apparently make our bodies feel way too excited.

As a consequence, Korean temple chefs have become masters of foraging, fermenting and dehydrating food. It’s why so many chefs are visiting the country to learn techniques that will give their own food more flavour. Kwan maintains vats in which she pickles and ferments food for years before eating, with her soy sauce kept waiting for a decade.

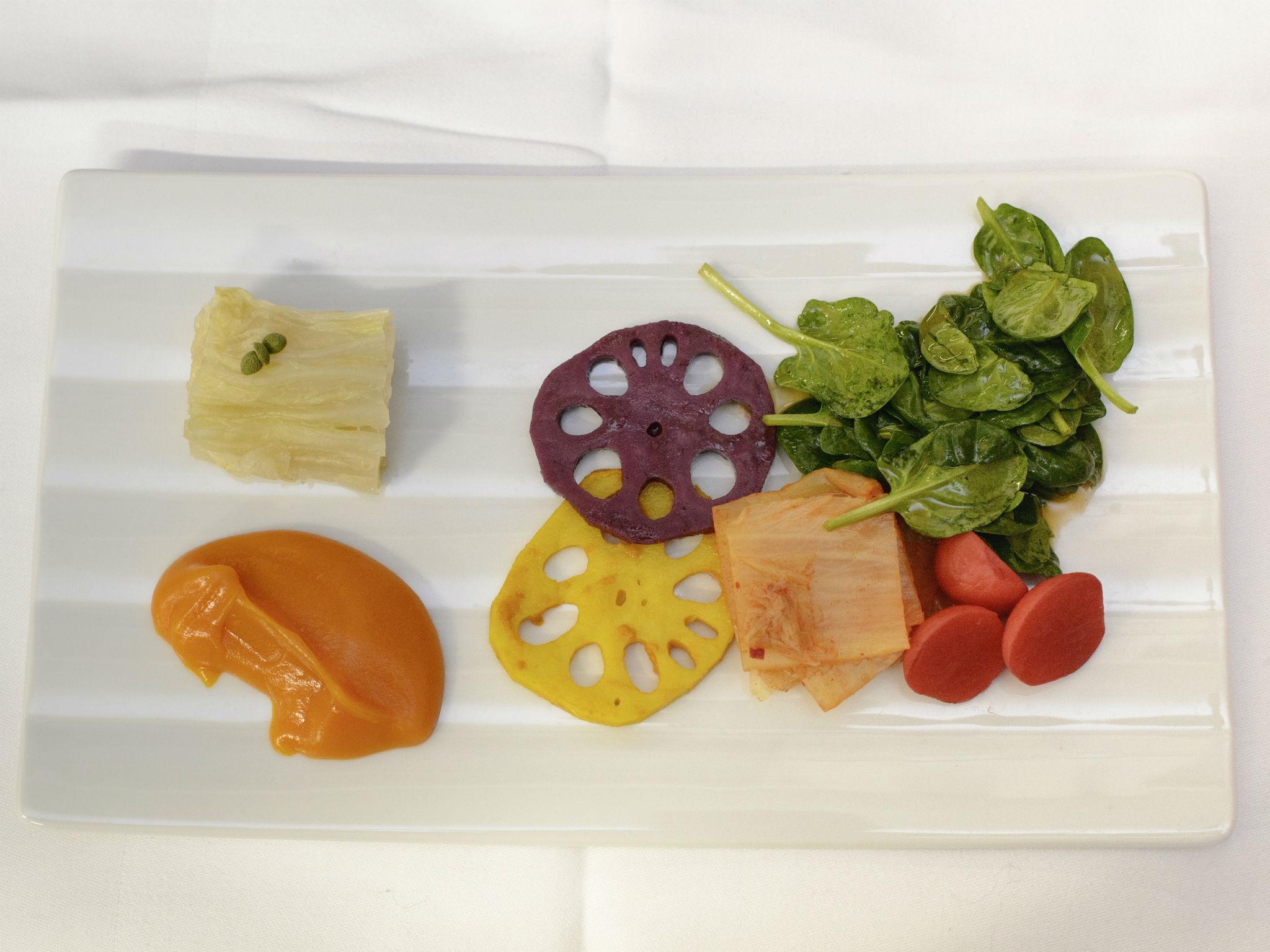

Raue is trying to recreate one of Kwan’s dishes in a temporary restaurant. So it’s all the more remarkable that his Winter Garden is excellent, especially the spinach with sesame oil and soy sauce.

Ruae is known for the mixture of traditionally eastern spices in his food. He claims, “I want my food to be strong. I’m not a fan of the delicate balances of French cuisine.” Indeed, after he was awarded his first Michelin Star, he shocked his peers by announcing he was going to create a restaurant offering more earthy, spicy tastes that he discovered when travelling in Asia.

Some of his vegetables had an almost Indian flavour. The colourful plate contained pumpkin puree, kimchi, radishes and nashi pear. It was a burst of flavours, slightly uneven in taste, but done sufficiently well to make me more curious as to what the food must be like when Kwan cooks for her visitors at lunchtime.

The two main dishes were variations on dishes cooked at Tim Raue’s restaurant. Arriving back on stage to present it, Raue said that the next dish on the menu, the Wasabi Prawn, was a variation on his signature dish, the Wasabi Langoustine.

Raue explained that in cooking for so many guests he needed to make the dish with an ingredient that is more stable and amenable to different room temperatures. But then he appears to be more vulgar, adding that the langoustines he buys cost €9 (£7.60) each, with the dish at his restaurant costing €108.

When I meet him the next day for an interview, Raue rationalises his comment so well that again I find myself liking him more and more. He adds that in Germany no one wants to talk about the cost of food. It’s expected that British chefs such as Gordon Ramsay and his friend Jamie Oliver open numerous establishments, but Raue gets asked by Germans if it’s a bit “too much that he has three restaurants in Berlin”.

He admits: “I want to be a billionaire chef.” In pursuit of this goal he recently opened a restaurant in Dubai called Dragonfly, which he informs me is a “one-to-one replica” of his signature restaurant in Berlin.

On stage he also mentions that when he watched the show featuring Kwan, he saw a demonic glare in her eyes when one of the students she teaches did something wrong. He says, “She’s not so different from me, I can see she gets mad in the kitchen.” Kwan laughs and agrees with the assessment.

The prawn during the post-screening dinner is absolutely sensational. The wasabi looks as green as the Hulk, but is as mild as Bruce Banner. It leaves me trying to work out if €108 is an acceptable price to pay for a single dish.

Next up is a Cod dish. It’s getting late in the night, and it’s a big portion. The sauce contains an incredible cocktail of water, chestnuts, hazelnuts, grapes, chillies and Jerusalem artichokes. But it’s when crunching into the nuts hidden at the bottom of the plate where the delights are to be had.

The meal is ended with some fine chocolates.

The next day I also meet with Kwan. She tells me through a translator that she felt ecstatic about being honoured by Raue; “I thought that the setting was very Asian, especially the red kimchi and the white kimchi impressed me very much. My hope is that the people who ate the food will have felt the calm energy.”

I also ask why a monk would appear on a show such as Chef’s Table that seems pretty commercial. “I don’t have any fixed recipes. But I wanted to share my philosophy of food and the spirit of Buddha.”

At the event, Tim Raue has some signed-books for sale, the staple of any chef. Kwan admits that she is now considering writing a book. It seems that while it’s Raue who talked about needing to take on some of Kwan’s calmness that it’s actually Kwan who’s taking more on board.

It seems that these chefs are not so much yin and yang but bibimbap (mixed rice).

‘Chef’s Table’ season three is now available exclusively on Netflix

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks