Movies You Might Have Missed: Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb

The documentary about the underground cartoonist Robert Crumb proves the old saying that truth is stranger than fiction and explores the relationship between mental illness and artistry

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

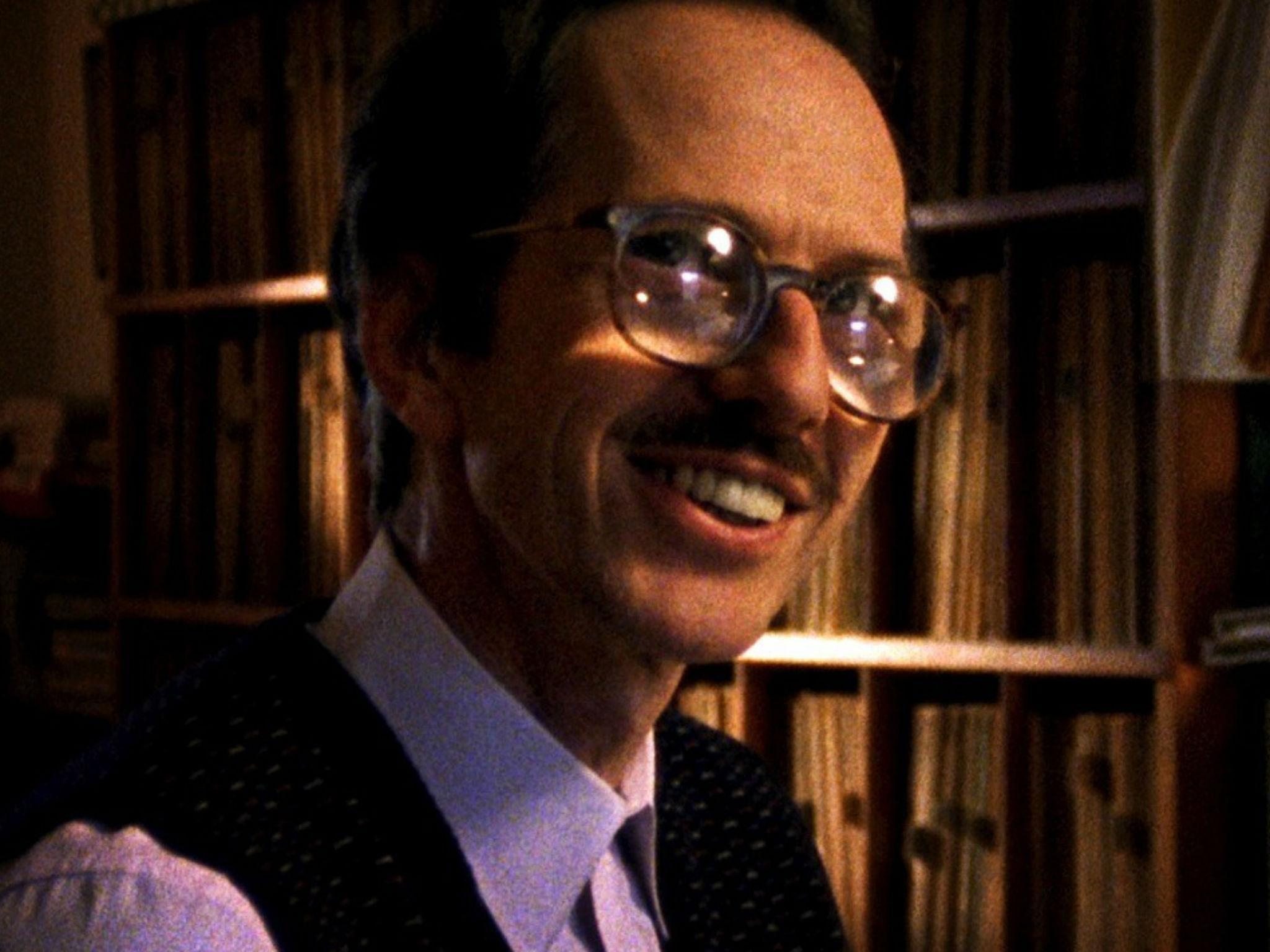

Your support makes all the difference.At one point in Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb, the documentary’s main subject confesses to being aroused by Bugs Bunny. Astonishingly, this man turns out to be the most well-adjusted member of the family. This is no typical tribute to an artist comprised of endless footage of fans extolling the virtues of their hero. Even the title suggests Zwigoff is interested in the family as a whole rather than simply the celebrity in their midst.

Zwigoff is best known for Bad Santa and Ghost World, films about isolation and longing with more than their fair share of misfit characters struggling to get by in the world. His breakthrough, Crumb, proves the old adage that the truth is stranger than fiction and centres on the legendary underground cartoonist Robert Crumb and his two brothers. Rarely can a documentarian and his subject have been so perfectly aligned and the result is unlike anything else committed to film.

The director worked on the film for nine years and later said he was “averaging an income of about $200 a month and living with back pain so intense that I spent three years with a loaded gun on the pillow next to my bed, trying to get up the nerve to kill myself.” This is a portrait of the artist as a strange man made by a similarly iconoclastic figure.

For some, this will be too much to bear and cinema walkouts were not uncommon at the time of the film’s release. During the years of filming, Charles Crumb, the older brother of the artist, was still living with his mother in the family home and rarely ventured outside. He emerges as a tragic figure and Crumb is dedicated to his memory since he committed suicide prior to its release. The film’s producer, David Lynch, was so taken with the man that he had considered writing a screenplay for a film for him to star in. Maxon, Robert’s other brother, is a man tormented by his own demons and the frank discussion of his sexual desires is uncomfortable in a manner almost unparalleled in cinema.

Every documentary has an element of artifice but this one feels more honest than most. The central figure is presented as disturbed, selfish and misogynistic and one can almost smell the family home where he sits and bickers with the matriarch. When he was trying to raise funds, Zwigoff asked Terry Gilliam for help with the budget since he knew the filmmaker had worked with Crumb in the 1960s. Gilliam reached into his pocket, handed over a nickel and then walked away. Clearly making the film was a labour of loathe for Zwigoff but his perseverance paid off and the result is one of the finest explorations of mental illness and artistry, and the relationship between the two, in any medium.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments