Monetary frights at the movies

As unemployment and ticket prices both rise, will young adults be able to afford a trip to the cinema? Geoffrey Macnab reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

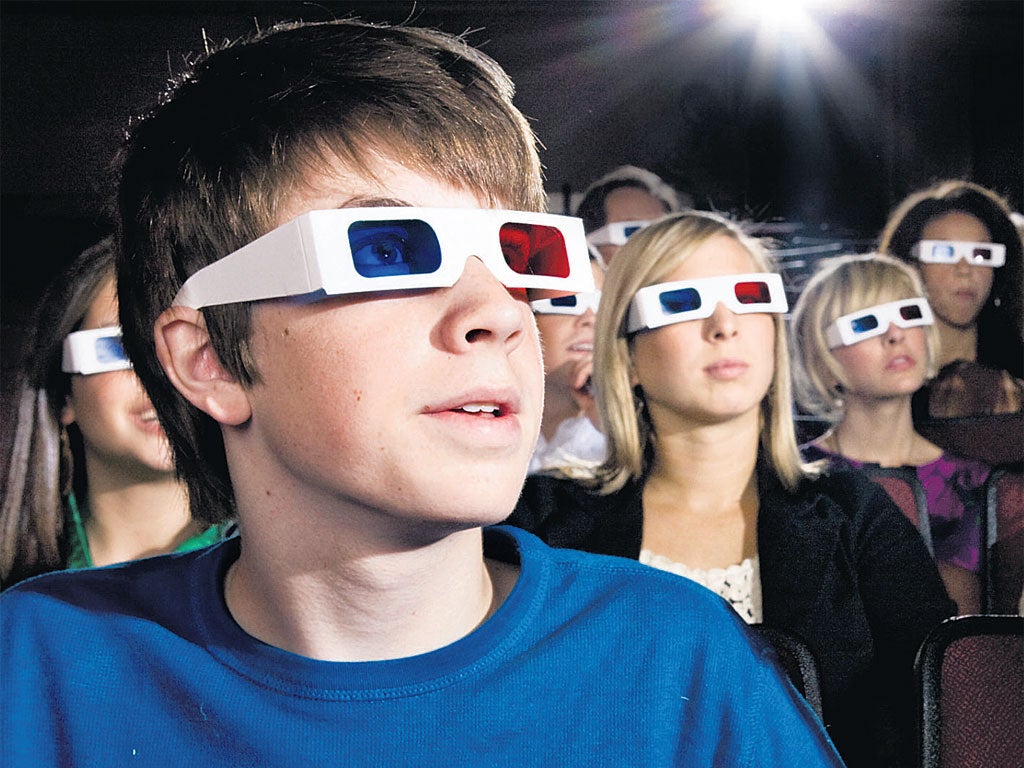

Your support makes all the difference.These are contradictory times for cinemagoing in the UK. For the cinema-owners themselves, optimism and extreme anxiety seem to go hand in hand. Box-office appears to be booming. For three years in a row now, the Brits have broken the £1bn barrier in takings at the box-office. Cinema admissions in Britain stand at around 170 million a year – a healthy number by comparison with the 54 million admissions the Brits mustered back in 1984. There are almost 4,000 screens in the country. The 3D boom prompted by James Cameron's Avatar in 2009 gave cinema-owners a huge windfall and helped finance the transition to digital. The audience base has been expanding, too. Partially thanks to films such as The King's Speech and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, older (over 45) spectators are going to the movies in increasing numbers and now make up 30 per cent of the overall cinemagoing audience.

Scrape beneath the surface gloss, however, and some worrying trends quickly become apparent. As David Puttnam recently noted, unemployment among 16- to 24-year-olds in the UK broke one million for the first time last year. "This amounts to one in five of that age group, traditionally the most frequent cinemagoers."

At the same time, the cost of cinema tickets has continued to rise. There is a growing threat that a new generation of young adults simply won't be able to afford to go to the cinema.

Another question is whether the young audience will still want to go to the cinema when there are so many other ways of watching films.

It is hard to credit now that cinemas used to be the only places where you could see movies. At a British Screen Advisory Council (BSAC) conference in London last month, attendees were told by an industry analyst that in this brave new digital age, there are now around 16 different ways in which films are watched by British movie enthusiasts. These range from the gigantic IMAX screen to the tiny portable device. In spite of continual predictions of its imminent demise, the DVD market remains resilient, albeit that Blu-ray has proved a disappointment. It has become far easier than before to stream films online. With broadband speed and digital technology improving all the time, the idea of having a cinematic experience in your front room no longer seems far fetched.

Cinema attendance has remained static. The increased box-office revenues trumpeted with such enthusiasm by trade bodies each year come largely from the rise in ticket prices. Exhibitors have used 3D to justify putting a hefty surcharge on tickets. Now, even if a film isn't being screened in 3D, there's a fair chance that spectators will still be invited to pay extra to see it with enhanced seating and sound.

No one really knows whether or not 3D will retain its popularity with British cinema audiences. In 2011, there were hints that these cinemagoers were either falling out of love with the format – or growing exasperated at having to pay extra to watch 3D movies. While several 3D movies nestled near the top of the box-office lists for 2011, their overall share of the market was in decline. There were 45 3D films released in 2011, generating £235.8m at the box-office. This doesn't compare at all favourably with the £241.8m generated by only 28 3D releases in 2010.

It will be revealing to see how British audiences react to a big-budget, character-driven, "literary" 3D movie such as Baz Luhrmann's adaptation of The Great Gatsby (released later this year). Cinemagoers who are willing to pay extra to watch James Cameron-style spectacle may balk at having to spend those extra pounds to watch Jay Gatsby and Daisy Buchanan make mooncalf eyes at one another.

In spite of the huge technological changes in film-making and film distribution in the digital era, the British film industry is still run along surprisingly traditional lines. One principle that remains sacrosanct to the US studios and their British offshoots is "windows". This is the idea that films will travel in an orderly way, at staggered intervals, from the cinema to DVD, then on to pay-TV (or VoD) before turning up on free TV. Whatever the risk of piracy or audience fatigue at being made to wait to see movies that they've heard about months before, many cinema-owners cling doggedly to the old way of doing business. They react with fury when distributors try to circumvent the usual release patterns.

One British distributor who rejects the idea of staggered releases is Philip Knatchbull, CEO of the Curzon Group. As Curzon owns its own cinemas, Knatchbull doesn't need to worry about upsetting exhibitors. He doesn't distinguish between releasing films in Curzon's London cinemas or making them available at the same time to anyone who wants to download them on Curzon's "home cinema" platforms. The cost is roughly the same. The cinemas themselves he describes as "shop windows" and "entertainment venues".

"Theatrical," the Curzon boss declares, "is simply one small part of the offer." His mantra is that cinema, whether watched at home or in public, is "one thing". One initiative Knatchbull has recently hatched is "franchising" out the Curzon brand. If an arts venue wants to turn itself into a part-time Curzon cinema, he and his team will provide a "flight case" complete with digital projection equipment. The idea is to provide communities without their own arthouse or multiplex cinemas a chance to see the latest films.

Curzon specialises in upscale, arthouse movies, likely to appeal to affluent, older cinemagoers. The company is not targeting the teen audience. It is too early to suggest that 16- to 24-year-old filmgoers are disappearing from British cinemas. The group still makes up the bulk of the audience, even if last year saw a small decline in its cinemagoing. The Inbetweeners Movie grossed £45m at the UK box-office last year – a sign that teens and young adults can be lured to local cinemas in huge numbers. Nonetheless, when tickets to London's West End cinemas can cost close to £20 and youth unemployment is at record heights, it's a fair prediction that this is one sector of the British audience unlikely to be growing any time soon.

Should the exhibitors be worried that their core audience is about to vanish? Mark Batey, Chief-Executive of the Film Distributors' Association, argues that cinema in our age of austerity remains "affordable escapism" for even cash-strapped younger filmgoers. When films such as The Dark Knight Rises are released this year, the 16- to 24-year-olds will come out in droves. Others are not so optimistic. They fear that if there isn't some flexibility with ticket prices and windows, much of the core audience may soon be lost.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments