Marianne and Leonard: What happens when documentary-makers put themselves in the story

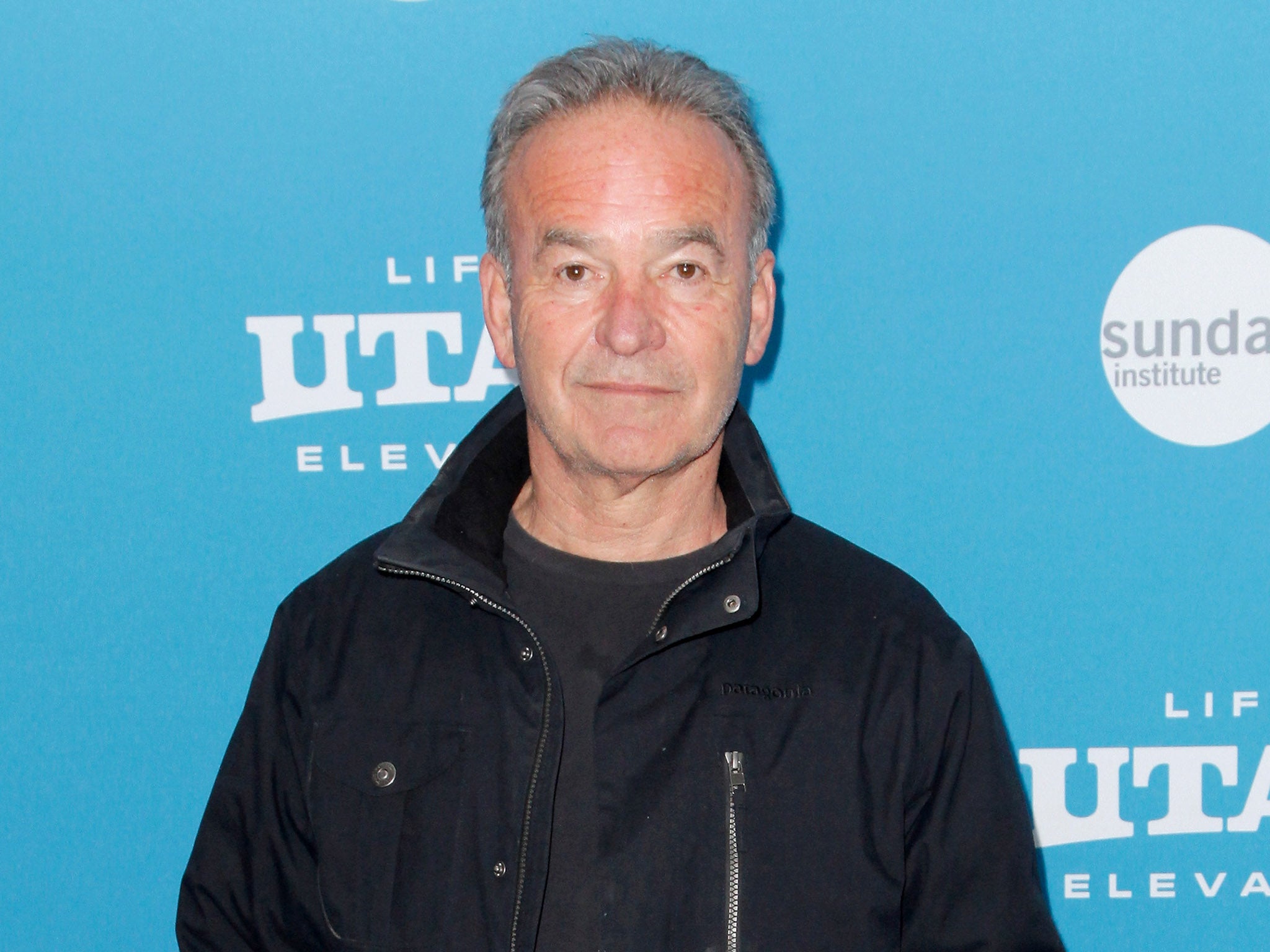

Inside Film: Nick Broomfield’s new documentary explores the relationship between Leonard Cohen and his lover and muse, but does the director’s own involvement disturb the narrative?

Nick Broomfield’s new documentary, Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love, should really be called Marianne, Leonard... & Me. The film ostensibly tells the story of Canadian troubadour Leonard Cohen and Marianne Ihlen, who met and fell in love on the Greek island of Hydra in the early 1960s. But there is more to it than that.

Broomfield portrays Hydra in this period as a hidden, counterculture paradise, rife with drug-taking and party-going, where artists, hippies and poets could live on $1,000 a year. But it wasn’t all sun-kissed hedonism. This was where Cohen, the Jewish aristocrat from Montreal, was at his most creative. Ihlen brought him food and drink while he “wrote and wrote and wrote”.

Their relationship foundered as Cohen’s fame grew, but the pair stayed in touch for more than half a century. Cohen sent his final, immensely poignant message to Ilhen days before she died in July 2016, and just a few months before his own death later that year: “Our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon. Know that I am so close behind that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine.”

Early in the documentary, which is screening next week at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, Broomfield lets drop a startling revelation. He also visited Hydra in the 1960s, when he was an aspiring young photographer, and for a short while, “as a rather lost 20-year-old”, he was one of Ihlen’s lovers too. “She encouraged me to follow my dreams and she played me Leonard’s music under the Greek moon and stars. Her smile and enthusiasm were one of a kind.”

Like Cohen, Broomfield stayed in touch with Ihlen. Without their encounter, he might never have gone on to make award-winning films like The Leader, His Driver and The Driver’s Wife (1991), Kurt and Courtney (1998) or indeed Marianne & Leonard itself. She was his muse, too.

The disclosure of Broomfield’s affair with Ihlen changes the tone of the film. This is no longer a detached study of the decades-spanning relationship between Cohen and Ihlen. It’s a story told from the inside. The director isn’t just an observer and narrator. He is one of the characters, with skin in the game.

Of course, documentary-makers are often drawn into the stories they are telling. They befriend subjects, or at least become a grudgingly accepted part of their lives. Broomfield regularly features in his own films, infuriating white nationalist Afrikaner leader Eugene Terre’Blanche by turning up late for a meeting, or trying to secure an interview with an elusive Courtney Love. He will be shown on camera with his headphones around his neck or carrying a microphone at the end of a boom, looking strangely like an adventurer on a safari. We will hear that familiar drawling voice describe the latest predicament in which he has landed himself.

Similarly, you couldn’t imagine a Michael Moore documentary in which Michael Moore wasn’t front and centre, being Michael Moore. A polemicist, showman and comedian, he has turned traditional ideas about self-effacing documentary directors on their head as he guides us through dark and complex arguments about gun law and healthcare in America, or Donald Trump’s fascist tendencies.

There is a difference, though, between a filmmaker appearing on camera as they pursue a story and a filmmaker who is already part of that story to begin with. On the one hand, in his new film, Broomfield can provide far more intimate insights into Ihlen than those who had never known her could have done. On the other, he risks compromising the story he is trying to tell. He is the gooseberry, the third person on the date. We are watching an intense, very personal account of the five-decade relationship between a poet and the woman who inspired his best-known songs – and Broomfield keeps on interrupting to tell us how Ihlen came to visit him in Cardiff Docks. Broomfield’s relationship with Ihlen is interesting enough in its own right, but the nagging thought remains that it belongs in a different movie – or that it could have been dealt with in a footnote at the end of this one.

Even documentary-makers who try to uphold the principles of “direct cinema” and to remain as unobtrusive as possible regularly find themselves prised out from behind their cameras. The late Albert Maysles might initially have regarded Gimme Shelter (1970) as a music movie, but the footage he and his brother David recorded of the Rolling Stones’ chaotic concert at Altamont in 1969 famously became part of a criminal investigation. They had caught on camera the moment when Alan Passaro, a member of the Hell’s Angels, in charge of security at the venue, allegedly attacked and killed 18-year-old Meredith Hunter. The jury were shown clips from the film during Passaro’s murder trial. (Passaro was found not guilty.) The Maysles’ documentary wasn’t just a record of the concert but a key piece of evidence in a court case. The filmmakers had crossed an invisible line and become protagonists in the Altamont story, rather than just its chroniclers.

Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line (1988) is known as the film that saved a man from death row – but Morris ended up being sued by his subject on the grounds that he had “stolen” the man’s story. The irony is that without Morris’s painstaking research and dramatised reconstructions of the crime, the man wouldn’t have had a life to steal anyway.

Any documentary directors investigating Scientology invariably end up having cameras trained on them. Whether it’s Louis Theroux in My Scientology Movie (2016), Alex Gibney in Going Clear (2015) or reporter John Sweeney in Scientology and Me (2007), the filmmakers are put under surveillance by the very people they themselves are trying to film. They may not be the subjects of their own films but they are of somebody else’s.

In an era of lightweight digital cameras and mobile phones, personal films have become increasingly commonplace. Filmmakers put themselves at the heart of their work in a way that would have been inconceivable in the days of cinema verite. They tell us about their chequered love lives, their ailing relatives or their unhappy childhoods.

It’s clear now that Ross McElwee’s Sherman’s March (1985) was a forerunner of what was to follow, as filmmakers increasingly began to gatecrash their own movies. We think we are watching a film about the American Civil War and Union General Sherman’s famous 1864 march to the sea. In fact, the film isn’t really about Sherman at all. The director, who is from the south, tells us that when he was about to start shooting, his girlfriend told him she was leaving him and going back to her former boyfriend.

“What I really need to do is find a nice southern girl and things will be fine,” he says. The film chronicles his search for such a partner, and somehow turns from a piece of historical research into a dating movie. The director’s camera becomes a matchmaking tool. Sherman’s March is self-pitying, narcissistic and very original in its own comic way. McElwee’s matter-of-fact voiceover, in which he describes his romantic misadventures as if he is narrating a dry, factual film, adds to its absurdist feel.

When McElwee made Sherman’s March, the idea of an unknown filmmaker devoting an entire feature documentary film to his unhappy love life seemed bizarre in the extreme. Thirty-five years later, it’s a surprise when new directors make films about anything else.

Thankfully, Broomfield generally keeps himself in the margins of Marianne & Leonard. It’s really about how Ihlen inspired Leonard Cohen as a poet and performer, how their lives went in such different directions after their first idyllic encounters on Hydra, and how they still maintained such a close bond over half a century, until the last weeks of their lives. It’s a moving and insightful film, with far more grain and depth that the typical rock star bio-doc. In a way, it’s a moot point whether the director’s personal revelations add anything to it.

Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love screens at Edinburgh International Film Festival until 30 June, and is released nationally Friday 26 July. Nick Broomfield appears as part of In Person: Special Events, Friday 28 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks