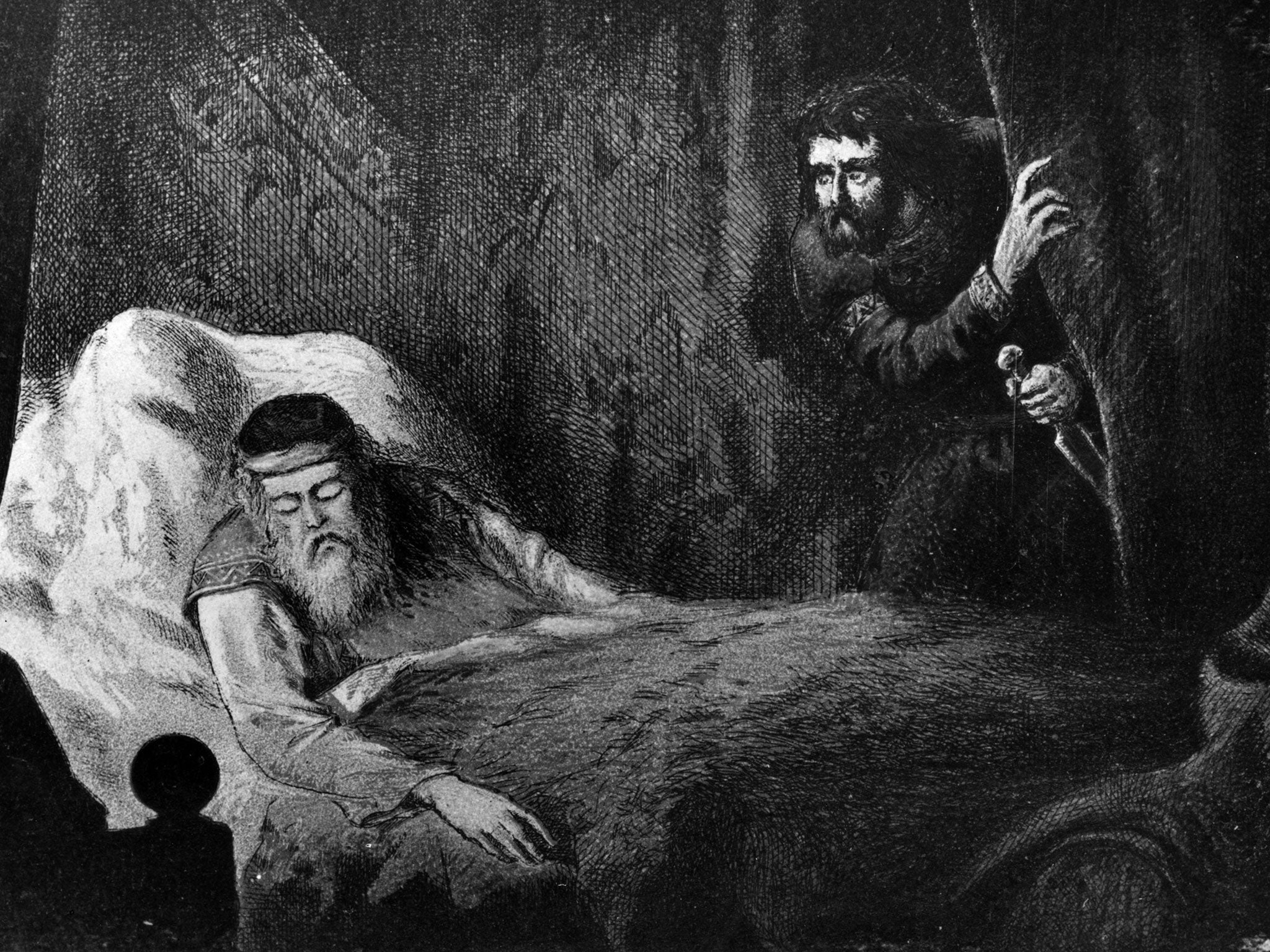

Macbeth: Shakespeare’s tale of a paranoid killer strays far from the facts

A new 'Macbeth' film is out today, peddling the Bard's tale of a paranoid killer. In fact, he ruled Scotland very well for 17 years, says Catherine Wells, author of a novel about him

It's hardly a revolutionary idea: the first film of Macbeth was made in 1908. Orson Welles, Antony Sher, Ian McKellen – even John Pertwee – have all taken the role on celluloid. It's been adapted for movies set in a Glasgow chip shop and in Mafia turf wars. So the vaguely medieval new Macbeth starring Michael Fassbender will not upset any expectations. But what might is the true story on which Shakespeare's drama was based.

Historians have known for some time that the historical Macbeth was not the blackguard Shakespeare portrayed (using the best sources available to him at the time). But the Macbeth who succeeded Duncan as King of Scots was probably a very good ruler who kept the peace (mostly) and introduced humanitarian laws.

How did the tale get so twisted? The biggest reason is that history is written by the victors –in this case, the English. They viewed Macbeth through the lens of their own culture, and to top things off, later purged all Scottish literature written in Gaelic. What was finally recorded was heavily influenced by oral tradition and classic Celtic exaggera-, ah, storytelling.

To reverse the filter, we must understand that in Celtic cultures, the arigh, or king, was not normally succeeded by his son. Succession sometimes went to a brother or a nephew, but more often leadership passed back and forth between two royal houses. A king selected his tanist, his successor, from among the able warriors of the alternate house. Frequently the tanist got impatient and challenged the king, resulting in an average tenure of five or six years.

Malcolm II was a notable exception. On coming to power, he eliminated potential tanists in the alternate house and ruled for 30 years. He also named his own grandson, Duncan, as his successor, in defiance of accepted tradition.

Now add to this mix a sharp division between northern and southern Scots. Both royal houses came from the south, and just how far north their rule extended is questionable. In fact, Irish annals referring to the “King of Scots” generally mean the ruler of of Moray, in the north, rather than the “high king” at Scone. Several battles are recorded between the north and south, with the south rarely the victor.

Macbeth was of the House of Loarn, a one-time royal line that continued to rule in Moray. He was called the mormaer or steward of Moray, indicating allegiance to Malcolm II – although such allegiances were sometimes hard to enforce. When Macbeth defeated Duncan in battle – not by treachery – he claimed the throne in his name and that of his wife, Gruoch (who belonged to the royal house that should have taken over from Malcolm II).

Was he driven by “ambition that o'erleaps itself”? We'll never know. But we do know that Duncan had a poor track record as king. Prior to his defeat by Macbeth, he led a disastrous battle against the English at Durham, where 3,000 Scots died. This was a warrior culture, and a king's power was based on the size of the army he could call on. After Durham, it is questionable whether his vassals were willing to support Duncan's military endeavours.

The King of Scots, or “high king”, had to be confirmed by his peers and the Church. Because Macbeth was duly installed, we can assume that was the case. And because he held Scotland's borders for 14 years, we can assume he had the ability to muster troops. But in 1054, Duncan's son, Malcolm Canmore (or “Big Head”), backed by Siward of Northumbria and the English king, invaded Scotland and struck Macbeth a serious blow.

The battle took place outside Dundee. (Dunsinane is an old hill fort nearby, and we're not sure why it became associated with Macbeth's defeat.) The English claimed victory but withdrew, and what happened to Canmore at this point is unclear. Three years later, Macbeth either died or was mortally wounded in a small skirmish outside the village of Lumphanan in northern Scotland. Had he retreated to his home province of Moray after Dundee? Was the kingship in question for three years? We simply don't know.

We do know that Lulach, his wife's son from her first marriage, succeeded Macbeth, only to be killed by Canmore or his followers a year later, and treachery can be inferred. Canmore, raised in the English court, brought English ways and English governance to Scotland. And the era of Celtic high kings was over.

'Macbeatha', Catherine Wells' novel about the real Macbeth, is published by Desert Moon Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks